rev. of The Only World by Lynda Hull

The Only World

Poems by Lynda Hull. HarperCollins, $22.00 cloth, $12.00 paper. Reviewed by Diann Blakely Shoaf.

The term

mimesis, unfortunately having come to be redolent of tweeds and pipe smoke, seems wildly inapplicable to a poet as inspired by the exhaust-fumed ether of today’s cities and the musky glamour of their earlier incarnations as Lynda Hull. Yet the classical scholar Gilbert Murray reminds us that the term we usually translate as “imitation” originally implied not a mirror held up to nature, but a fracturing of that mirror — indeed, of all borders between the self and the objective world that urges song. The notion of mimesis, having evolved from the ritualistic chants and dances from which Greek poetry sprang, takes a quantum and very contemporary leap in Hull’s work, becoming a raw, even savage means of breaking down the “I” into otherness, into points of view that are “multiplying and dazzling,” as she writes in “The Window,” the shattering but finally redemptive poem that concludes her posthumous collection,

The Only World.

Hull loses herself again and again in

The Only World’s coruscating but gritty panoply of subjects. Junkies and whores, the imprisoned, the beggared homeless of our urban landscapes, those dying or dead from AIDS, do not merely “appear” in these poems, they become past or future selves, alternate selves, feared selves. Hull’s poems serve as vessels for human stories that constitute, as she says in “Suite for Emily,” “doors you (I?) might fall through to the underworld / of bars and bus stations, private rooms of / dancing girls numb — sick & cursing the wilderness / of men’s round blank faces. Spinning demons.”

Such doors imply the psychological and spiritual brinks Hull writes about in “Lost Fugue for Chet,” one of the tours de force of her second book,

Star Ledger, which won the 1990 Edwin Ford Piper Award. “Why court the brink & then step back? / / After surviving, what arrives?” she asks there, and these questions, grand rhetorical flourishes with a stern moral fervor at their core, are asked and answered with even greater artistry and more stringent self-examination in

The Only World. The various brinks that ecstasy — religious, sexual, chemical — leads toward in Hull’s poems are always alluring, even as their sirening whispers sometimes smell sourly of death. The survivor of such brinks arrives only and always at other occasions for survival, but such occasions can provide the burden and opportunity of witness.

“Street of Crocodiles,” the swirlingly cinematic poem written after Hull’s 1991 trip to Poland, a trip made with her mother in hopes of locating what fragments of family remained there, provides one of

The Only World’s most exemplary moments of reckoning with the personal and historical past, giving voice to those otherwise choked and silenced. Some of Hull’s forebears were “to be dealt the yellow cards of the murdered, to know / / the must of between-the-secret-convent-walls.” Such fates were suffered during the era of Auschwitz, with its “shorn hair / of 40,000 women turned gray by Zyklon B, / the piled canisters and shoes.”

How to sing in such a world? How do we make songs of the notes history jams down our throats, songs that are “crucial and exacting” but not despairing? Mark Doty, whose afterword provides a clear-eyed benediction, also provides an answer to these questions. “Glamour,” says Doty, “is a way of making history bearable.” And in the songs of Lynda Hull, the term glamour, like mimesis, skyrockets beyond the usual definitions, becoming an ethical force, a survivor’s gaiety, and a poetic imperative. In

The Only World, artifice is not to be confused with frippery; it is at those moments when we try most ardently to be something or someone else that we are sometimes fortunate enough to be launched hardest into the process of becoming our own multifaceted selves. As Hull writes in “The Window,” “If each of us / contains, within, humankind’s totality, each possibility / then I have been so fractured, so multiple and dazzling / stepping toward myself.”

The word fractured indicates the risk involved in such willing transformations, and it became a word with more than metaphoric implications in Hull’s life after a December 1992 accident: a taxi slammed into her car, smashing both her feet and ankles. The conversation with Lynda — whom I am blessed to remember as mentor and “girlfriend,” as we called each other when feeling silly — that I remember best during her long convalescence took place on a humid, rainy summer evening in 1993, approximately nine months before her death. Though trips outside her Chicago apartment continued to be painful and limited, I’d called to urge her to see

What’s Love Got to Do with It?, the lurid but somehow dignified biopic of Tina Turner, like Lynda a steel-backboned survivor and singer of brinks. Lynda loved being compared to makers of music like Tina, like Billie. Or Chet Baker. Or Bird, whose grave Lynda and fellow pilgrims visited on another humid evening, that one spent in St. Louis and retold in the poem “Ornithology,” originally published in

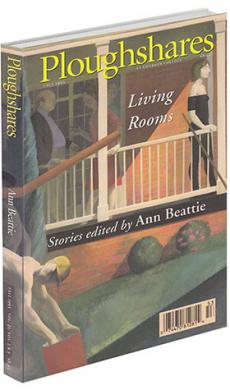

Ploughshares and ending with a line that represents one of Lynda’s many shining legacies: “If you don’t live it, it won’t come out your horn.”

The Only World contains both that life and that horn’s sweet, sad, ancient note riffing from praise songs to prayers for mercy to dirges. Its harmonies drift in the direction of God, certainly, but mainly toward this world, on it “each fugitive moment the heaven we choose to make.”

Diann Blakely Shoaf is a regular reviewer for the “Bookshelf.” Her collection of poems, Hurricane Walk,

was published by BOA Editions in 1992.