rev. of We Live in Bodies by Ellen Doré Watson

We Live in Bodies

Poems by Ellen Doré Watson. Alice James Books, $9.95 paper. Reviewed by Marcus Cafagña.

Ellen Doré Watson writes a poetry of elegy. The poems in her first book,

We Live in Bodies, seek consolation for all the losses that diminish the human body, the loss of life, the trauma of violence, even the slow degeneration brought on by age. With dazzling turns of phrase, her poems embody a speaker who, caught in the convulsive futility of grief, attempts to preserve at least the memory of what she’s lost, in this case, a miscarried fetus: “after you became a matter of blessed fact, a euphoric / knot of nausea I sat hugging, grinning my goofy /

we beat the odds grin — to have you dead in there.”

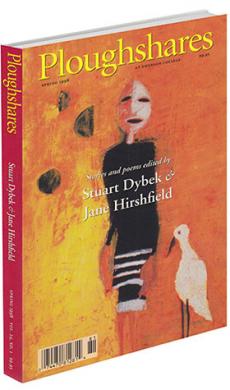

Like Larry Rivers with his painting for the book’s cover,

Me in a Rectangle, Watson both laments and celebrates the spirit housed in the body, trapped within walls, or made manifest by shape and form. With an unabashed sense of verve and humor (“Love — even forbidden love — doesn’t deserve linoleum”), these poems struggle against the lassitude and consequence of loss and refuse to accept age-old misrepresentations of the body. “Tenderness rarely appears,” her poem “What Gets Left Out of History Books” begins, “People don’t sigh. There’s no burping.” The poem’s meditation on starving children belies the complex metaphysical revelation beneath its surface: “The children in these pages wear distended bellies or tiny / crowns; they sing under a spotlight or lie in mass graves. / Where are the peach trees, the pies? Where are you and I?”

Watson’s elegiac verse is frequently composed in the second-person, her apostrophes most affecting when addressed to a former lover, “if you could know and believe / that while they wired and shocked you I was home breathing in / your blue workshirt, that my needing your smell on my skin / contained more electricity”; a child dying in an ambulance, “We sweep wind into her mouth / and her lips pink up. This allows us / to pretend she is alive”; or the battered toddler to whom she offers this advice: “Best to forgive them now, / before it gets worse; / that way you’ll have some / forgiveness left for later.”

Her unrelenting wit eschews theatrical posturing, so that lines like “If they beat all the life / out of you” consistently transcend their painful focus into “red dragonflies with wings half air, / half spun gold, gazillions of them,” and culminate in courageous and unexpected conclusions, so that cruel parental hands which pummel the toddler’s body “will rise up / and bear you to the warm basket waiting / beside the stove of God. Well. Whatever death / turns out to be, it will be one good mother.” These elegies address not only those who are dead or absent, but extol an acceptance, for all its vagaries, of the body as “the walk-in vanity, / the basementful of self-disgust. As old as peekaboo: I loves me, / I loves me not.”

In the tradition of Walt Whitman’s “I Sing the Body Electric” and the nineteenth-century physiological movement that called for the candid recognition of both male and female bodily functions, Watson — like the Brazilian poet Adélia Prado, whom she has translated — sounds this timeless affirmation. “We live in bodies clumsy and disobedient,” the book’s title poem declares, “and we love them even as we punish with too much or too little.” In poem after poem in

We Live in Bodies, “words hover fleshless in vowels and consonants” and, despite the persistence of bodily loss and suffering, bid us to drink from the “cup of having to go on.”

Marcus Cafagña’s book, The Broken World,

was selected for the National Poetry Series and published in 1996 by the University of Illinois. He has poems forthcoming in Boulevard, DoubleTake,

and The Southern Review.