140 Characters of Guilt

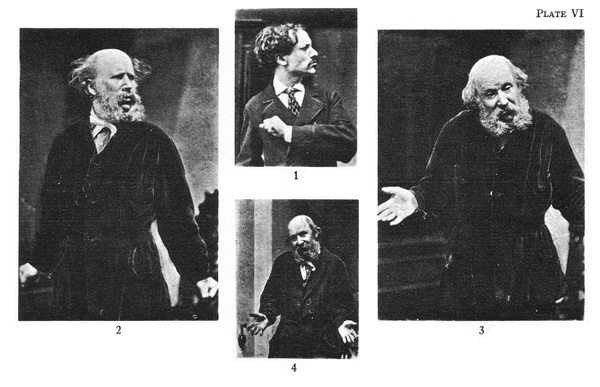

Plate VI from Charles Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

It took, it seemed, only a few seconds for the first response to appear. My heart plummeted as more appeared in my Twitter feed, each increasingly indignant, ticking off like a plunging stock exchange. I knew there had not been enough time for any of the commenters to actually read the article I linked to; they were simply responding to the post.

For many reasons—professional and deferential—I won’t repeat the exact content of the post, but it was the kind of thing that starts flame wars like dry underbrush. Blame it on laziness and a communal obsession with drama, but provocation sells. There is an art form to highlighting the main points of an article in 140 characters, especially one of a satirical nature, but if you do it “right” you have the chance to reach a potentially unsuspecting audience. At its best, a Twitter feed plays out like snatches of witty conversation heard on a subway while reading the newspaper. At its worst, it’s crude, manipulative.

So, I had a few options: I could write a rebuttal for the joke made in poor taste. Maybe accept that stirring controversy is not such a bad thing for web site numbers. Or, simply delete the tweet and hope no one noticed the blunder.

As Christopher Hitchens said in Love, Poverty, and War, “There can be no progress without head-on confrontation.” The thing is, I deleted the post.

And that’s where guilt set in.

Maybe it was an issue of not asking the right question when making my decision. Probably a more appropriate question would have been, do I owe anything to these commenters? I don’t know any of them personally. I’m not obligated to respond to comments, especially irate ones. So why, then, do I feel guilty for my action? Engaging in arguments in comment sections of the various social networks and web articles tend to be a fool’s game—glib, if not ignorant, incessant, and tendentious. No one has more to lose from engaging in this online argument than me.

However, isn’t that what’s great about this day and age: the transparency the Internet provides? We follow our favorite authors, athletes, and movie stars online, to earn a window into his or her private lives: Beyoncé’s Instagram; Kanye West’s Twitter account; the President of the United States himself. In a way, following these mythical creatures make us feel like we know them. I wouldn’t brush off any of my friends like I just did, so why would I do the same to my “friends?”

But, maybe it’s simply narcissism. A component of guilt is putting yourself in someone else’s shoes. How dare you ignore my comment would likely be the first words out of my mouth, if I were one of those deleted commenters—followed by a few more increasingly incoherent comments and Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No 2 on my keyboard.

I’m not alone, though. I have recently been reading Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, the controversial, three-thousand-six-hundred-paged examination of the writers’s family life. In unsparing detail, Knausgaard covers everything from his incontinent grandmother, to the failed marriage with his first wife and the bipolar condition of another. He told the New York Times, “When I first started to write this, there was something thrilling there, an almost insane energy. But I didn’t really think of how people would react as I did that…” So maybe, when writing the post, I subconsciously acknowledged it was wrong. But how can I fault myself for embracing the thrill of titillation? (I wouldn’t be the first to make a career out of such.)

By deleting the post, though, I abandoned my original position; avoided taking a stand. Was it the smart thing to do? Most likely. Do I feel good about it? No. The thing is, I’m not good with confrontations. Couples arguing on the subway. Turning to the last page of a book. My heart starts to race, my fingers go numb. I’d rather turn my gaze to the half-filled soda bottle precariously placed on the subway car floor than stop a fight. I read the last sentence of the book to settle my nerves before finishing the rest of the last page. I’m not a coward; I’m, simply, an avoider. My struggle, as Knausgaard’s, is the separation of ideologies and everyday life.

However, my guilt probably says more than anything else: a reminder that I’m human after all.