A Machine that Twitters: Why I decided to let Paul Klee title my essays

For about four years, I lived within walking distance of the Menil Museum in Houston. It’s a free museum lodged in the Montrose neighborhood and it ate hours of my life.

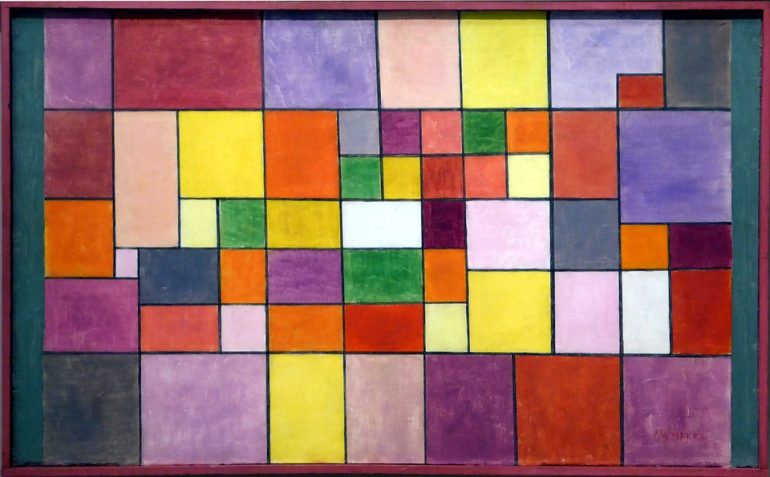

One season the museum had a giant mounting of Paul Klee’s work, the majority borrowed from other collections. If you don’t know who Paul Klee is, he was an artist who taught at the Bauhaus school until the National Socialist party exiled him.

The great thing about Klee is that his paintings have got the greatest titles. I would go into the museum and just write down his titles because there was enough humor and play and love of language in his titles to animate the interplay between the titles and what they supposedly titled (of course, they’re all translated from the German, but their music is stunning even in English.)

As a young man he excelled at the violin but at some point was forced to make a decision between art and music, and he was better at art. In his work there is an intense awareness of rhythm. He believed in rhythm as an animating feature of painting, the vestigial limb left over from his violin days.

Whenever I am stuck titling a piece I turn to my old notebook of his titles and that’s where the title of the piece that appears in this issue of Ploughshares comes from.

These are extra-medial forms of organization but every time I’ve titled something after his work, the essay or short fiction will begin to snap to.

I worked for a while vetting candidates for a Poetry professorship at the University of Houston and I noticed how often there would be poems about paintings. I noticed it enough (one note here is that if there is any artist that poets tend to gravitate towards, it’s Caravaggio. They can’t get enough of him.) that I learned the term for it: ‘Ekphrastic art’ – art that attempts to replicate the experience of a piece of art in a different medium. A foundational example of this is in the Iliad when Homer describes Achilles’ shield.

While I’ve never been able to generate a new piece from one of Klee’s paintings, I have turned over some of the organizational duties to them.

Which brings me to “The Twittering Machine.” It happens to be my favorite piece by Klee. Scrawny, under-feathered birds are perched on a mechanical crank – the promise being that if the crank is turned the birds will squawk. Underneath the birds is an abyss. The abyss is foreboding, but not in the morbid black nothingness we expect from that word. Instead it’s pink. Kind of flat and banal. A foreboding pink abyss.

How does this piece make sense out of my essay about running and death? Maybe it’s one of those things obvious only to me, but I feel allegiance with those birds. I could gush, but I’ll try not to. For me, I often feel like the self is jammed inexpertly into a system and it is this system from which music is expected.

I don’t know anything about death (I’m still stunned at how much more a group of rising sixth-graders knew about it then I did) but I frequently feel not in charge of the mechanisms that push music out of me. As a writer, I don’t get to determine subject matter (I’m prey to my experiences) and I don’t get to determine how people hear/understand my work. The crank gets turned and I try my best.

It’s not a direct ekphrastic activity that I’m engaged in in these Paul Klee essays and stories. Instead it’s an organizational one, a subliminal one. The painting and its title frame the work and set the tone. The world around me establishes the content. The writer in me is stuck on the perch and expected to sing when the gears go.

This to me is the experience of being a mortal and wrestling with death. It feels so abstract and un-natural and banal and foreboding but it animates so much of my conversations and thoughts about life that at some point I have to acknowledge that I’m tethered to it as I wait for the crank to get turned.