A Writer’s Envy, Part IV: The Heart Is a Telephone

Guest post by Scott Nadelson

Apparently, envy goes both ways. Just last week I had lunch with a sculptor friend who said he really wishes he could have been a writer, that he constantly struggles against the limitations of what his medium can communicate. He’s South African, and his work often deals with colonialism, oppression, and the conflict between guilt and nostalgia. The trouble is that he can never be sure whether viewers–especially American viewers–understand the culture and the history that his objects explore. Too often, he said, they just see pleasing forms and intriguing images and don’t think about what they mean.

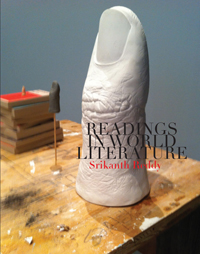

Andries Fourie, Keeping Madam Satisfied, 2009.

If he could just use language, he went on, he’d be able to be more precise, more direct. He could just say what he meant. He’d know that people were having the experience he wants them to have, that they were accessing his work in the way it’s meant to be accessed. He invoked the names of several of his fellow South Africans, J.M. Coetzee, Nadine Gordimer, Ingrid Winterbach, all of whom capture the complexities and contradictions of his homeland with a clarity and emotional resonance he can only admire and envy.

Of course I argued with him, complaining–as I’ve done in earlier posts on this blog–about the elusiveness of language and story, its abstraction and artifice, its approximation of visceral experience and reliance on simulation and illusion. We went back and forth, each beating up on our chosen medium, and then on ourselves as practitioners of that medium–the only person more self-deprecating than a Jewish writer is a guilt-ridden Afrikaner sculptor–and finally agreed that we’d both rather have been musicians.

There is one artist, however, who is the object of our shared envy: William Kentridge, my sculptor friend’s countryman, whose retrospective exhibition Five Themes is on display a couple of floors below the Marina Abramovic show at the Museum of Modern Art.

You never forget that someone is actively making these images, even as they are moving on screen, carrying you forward into a narrative. The process of creating the films is present in the finished product, and the result is work that feels incredibly personal: we experience the artist working through the process, physically and emotionally, as he puts his narratives together, painstaking frame by painstaking frame.

Until viewing Kentridge’s body of work as a whole, I hadn’t thought much about animation as a fine art form, though even the Saturday morning cartoons I loved as a kid had in them an element that defines the form’s possibilities. Think of Elmer Fudd arresting Bugs Bunny, the rabbit’s wrist securely in his handcuffs. But hold on! Suddenly it’s no longer a rabbit attached to the handcuffs but a bomb.

At the heart of all animation is transformation: from one frame to the next, we see new images, but because our brains are pattern-makers, we automatically fill in the gap between those images and make the connections that are missing. An arm becomes a bomb, and we don’t question it. Animation is uniquely suited to exploring radical transformations, and it achieves the surreal more efficiently than any other medium. Kafka can tell us that a man has turned into a bug, and we can make the imaginative leap; but the animator can show us the man turn into the bug, and we experience it as sensory fact. Within the world on screen, there is no question that the impossible or illogical has just happened.

In commercial animation, this kind of transformation is just a parlor trick, but Kentridge uses it to mine the depths of the psyche. In A History of the Main Complaint, one of his repeating characters, Soho Eckstein, lies ill on a hospital bed, surrounded by medical equipment monitoring his vitals. The film vacillates between the hospital and Eckstein’s fevered dream-state, in which we witness the violent and destructive cost of his capitalist exploits. At one point, doctors are listening to his heart, which turns into an adding machine, a stock ticker, and a ringing telephone. We watch the transformation, and out of it our brains make meaning: a heart that becomes a telephone is one that has been emptied of compassion and replaced by acquisition and consumption.

In his vulnerable state, we feel for Eckstein and the emptiness of his heart, despite his corruption. At the film’s end, however, when Eckstein is well again, he is surrounded only by the objects of his corporate, exploitative life–an adding machine, a stock ticker, a ringing telephone. His dream has taught him nothing, but we remain aware that his luxurious life is poisoned.

In his animations, Kentridge does what every writer does, and what my sculptor friend does, too: he makes metaphor. He takes an abstraction–the corrupting nature of capitalist exploitation–and makes it particular, sensory. Conversely, he makes the individual experience universal. Soho Eckstein stands in for all of us who benefit, directly or indirectly, from industrialization and exploitation. Eckstein’s heart becomes a telephone, and we feel our own hearts ringing with the corruption of the world around us.

Photos courtesy of andriesfourie.blogspot.com and the Museum of Modern Art.

This is Scott’s fourth post for Get Behind the Plough.