A Powerful Movie: Blind Mountain

Guest post by Fan Wu

When you tell people you are a writer, they often say that they’d love to read your books but just cannot find the time. “But,” they continue, “If they’re made into movies someday, I’ll check them out.”

Maybe it’s just a polite way to say, “I’m not interested in your books.” Or maybe busy people tend to watch movies rather than read books for entertainment or enlightenment. Once or twice I overheard people saying that movies might totally replace books. It doesn’t sound likely, in my opinion–at least not in our generation’s lifetime.

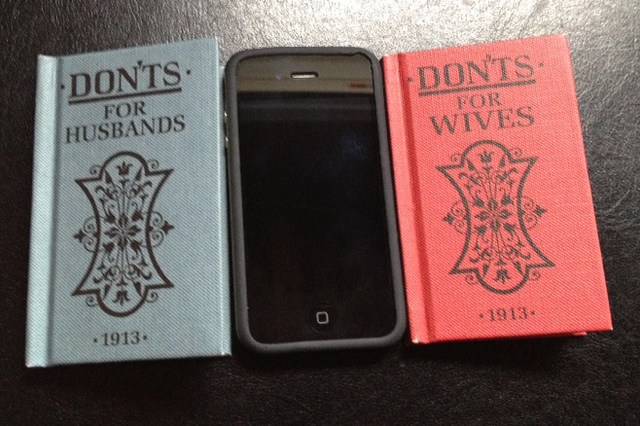

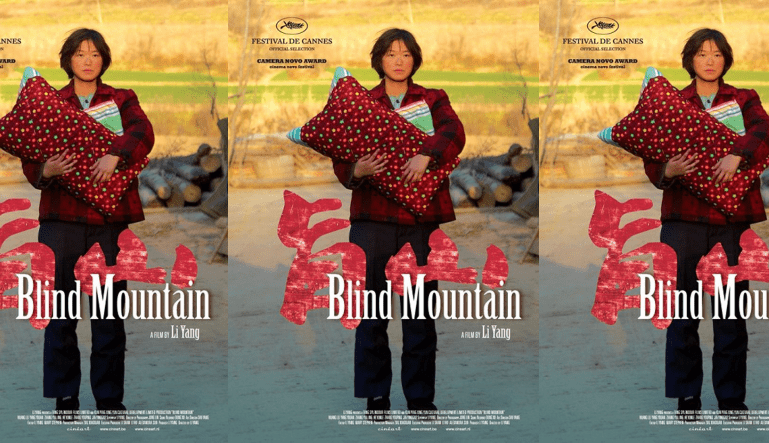

I like movies but if I must choose between a good movie and a good book, I usually pick the book (unless the director is a favorite). If I have already read a book and liked it, I usually don’t watch its movie adaptation: More often than not, the book is much better than the movie. Over the years I have re-read many books but I rarely watch the same movie twice. Blind Mountain, a Chinese movie directed by Li Yang, is an exception. If you’re planning on watching a foreign movie that’s not from Bollywood, you know my recommendation.

Blind Mountain is one of the saddest movies, also the best, I’ve seen in years. Bai Xuemei, a college graduate, is kidnapped and sold to a peasant in a remote village as a bride. Repeatedly beaten and raped, she tries to escape and refuses to give up even after she bears the man’s child. When hope finally arrives, she finds herself trapped in the idyllic mountain village and its corrupt social and legal system.

Though the cast’s only professional is the lead actress, Huang Lu, the overall acting is wonderful and entirely credible. The cinematographer, Lin Jong, also creates a stunning visual experience.

The story is disturbing. Being based on true events makes it even more so. It touches me profoundly not only because it is tragic but also because it reminds me of my roots, a country burdened with injustice and oppressive traditions, despite its recent economic boom.

The movie’s ending is perfect, leaving a lot to imagine. When the movie was released in China in 2007, it had a different, more upbeat and ironic ending, in an attempt to satisfy the censors.

The West’s reaction has been mixed. The movie received a standing ovation at Cannes but some critics gave lukewarm comments. “There’s little emotional underpinning to the rote story,” one said. Rote? How many movies about human trafficking are made each year? I don’t think it’s many. Also, a story can never be called “rote” if it provides new perspectives and cultural substances, as Blind Mountain does. (When I read that comment, I somehow thought of what an American once said to me: “I’m familiar with Asian literature.” Later, I found out that all the Asian literature he had read were several novels by an American-born Chinese writer.)

And “little emotional underpinning”? I could not disagree more. The emotion in the movie runs so thick and deep that I could barely breathe normally while watching it. The villagers’ matter-of-fact and unsympathetic attitude towards Bai’s suffering sends out a powerful message. Could this critic’s negative feedback result from his personal preference for being explicit as opposed to being implicit, and melodramatic as opposed to realistic? I don’t know. But to me, real life is implicit, subtle and nuanced much of the time, often not explicit when one might wish it to be.

This is Fan’s sixth post for Get Behind the Plough.