Activism in Exile

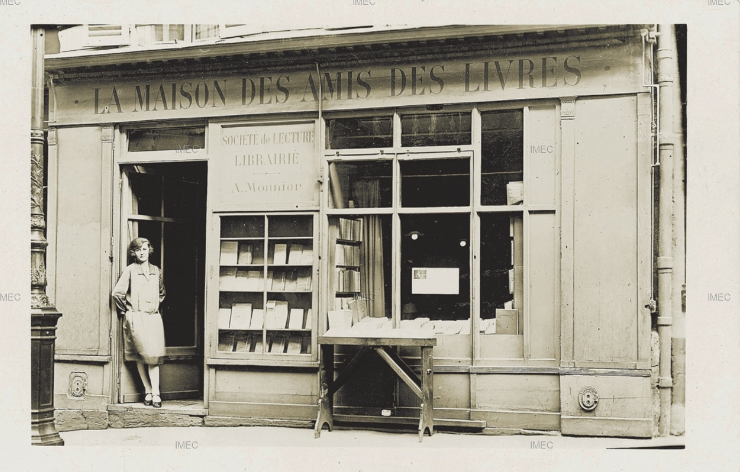

One Sunday in the spring of 1939, a group of avant-garde writers and artists, along with their friends and family, gathered at Adrienne Monnier’s bookstore, the Maison des amis des livres, on the rue de l’Odéon in Paris. They were there to watch a slideshow of color portraits by the photographer Gisèle Freund. For the makeshift event, Monnier fashioned a rudimentary screen out of a bedsheet hung in front of a wall of books and found chairs for fifty or so guests. Many faces who appeared on the screen in Freund’s photographs were part of the audience. According to her recollection of the event years later, it amounted to a rather awkward confrontation between the sitters and their projected portraits. “Those portraits,” Freund wrote, “considerably enlarged by the projector, which did not conjure away one skin blemish, were frightfully realistic.” As Freund willingly admits, the portraits are not particularly flattering. The slightly yellowed tone of the autochrome slides makes the sitters’ skin appear pasty, as if they had just lived through a harsh Parisian winter, and the portraits appear more solemn than vibrant. Sitters are posed with their faces resting against their hands, with furrowed brows, and lost in deep thought. Freund refused to employ poses or lighting techniques that would compliment her sitters, and such a public presentation of these frank portraits was apparently more than some literary egos could take. As Freund remembered it, the novelist Francois Mauriac jokingly asked her why she didn’t photograph him to look like he did twenty years earlier. Jean-Paul Sartre, who apparently brought his mother to the event, commented, “We all look as if we’d just come back from the war.” Though perhaps meant in jest, Sartre’s comment strikes me as more than an expression of vanity. He acknowledges, indirectly, that Freund’s photographs are a collective portrait of a community, rather than a series of individuals. His comment hints prophetically at the transience of this community—that this group of intellectuals, gathered for a Sunday afternoon in this venerable bookstore, would be scattered by the invasion of Paris by the Nazis one year later.

Whether or not she recalls Sartre’s comment accurately, Freund’s recollection also tells us about how she saw herself, an exiled German, fitting into this community. As a member of the Communist Student Organization at the University of Frankfurt in the early 1930s, Freund took up photography to contribute to the struggle against fascism. Depicting workers’ demonstrations and rallies, Freund, at that time, focused on the crowd. Due to her communist associations, Freund was under threat from the rising fascist regime in Germany, and she fled to Paris in 1933. She soon became friends with Monnier, who introduced her to many of the artists and writers she eventually photographed. Stylistically, the portraits displayed at the gathering in 1939 were a radical break from her photographs from Frankfurt. Her exiled condition and the community she identified with during this time warranted a new approach to the photographed subject. In other words, Freund’s photographs are as much a portrait of her as they are of the sitters, and the discomfort that these intellectuals reportedly felt viewing the portraits was due to their association with the circumstances of Freund’s exile more than their own vanity. This association articulated what those who gathered in Monnier’s bookstore might have already feared. In the near future, many of them would join Freund in her exiled status.

Although the slideshow presentation of Freund’s portraits associated the sitters with the conditions of exile, few of them would have considered themselves exiles in 1939. Paul Valéry and André Breton were lifelong Parisians. Virginia Woolf and T.S. Eliot had a close relationship with Monnier and the avant-garde circles associated with her bookstore, though both lived in England. The community that Freund presented was, in reality, less codified than her portrait series implies. Rather than representing a preconceived group, Freund attempts to imagine and define a community through this series of photographic portraits. It establishes a community at a moment of deep uncertainty, teetering on the brink of fragmentation and upheaval.

One way in which Freund attempts to articulate this community in her portraits is by situating them in a dialogue with history. When she began her series, Freund was completing her studies in sociology at the Sorbonne. Her thesis, entitled La photographie en France aux dix-neuvieme siècle, was one of the first histories of photography to link the development of the medium in the nineteenth century to the rise of the middle class. The nineteenth-century portrait photographer Nadar figures prominently in Freund’s history. She argues that Nadar’s approach to portraiture, which sought “not the exterior beauty of a face, but the inner spirit of a man,” was unappealing to the bourgeoisie. She emphasizes that retouching, which “robs the face, and turns it into a dry, lifeless image,” had no part in Nadar’s work. Her own portraits of bohemians were commercially unsuccessful because, according to her, she refused to “endow them with the beauty of movie stars.” Like Nadar, Freund highlights the intensity of the human face to facilitate its honest and direct communication with the viewer. Freund cropped many of the portraits from this series closely around the sitters’ faces to emphasize their direct and contemplative expressions. Like in Nadar’s portraits of the actress Sarah Bernhardt or the writer Charles Baudelaire, chins lean on hands to frame the face. Freund also insisted on photographing her sitters in their own personal surroundings, which required Freund to use artificial lighting; this resulted in sharp shadows and pasty complexions, creating what Freund called their “frightening realism.” In her portrait of Marcel Duchamp, the artist leans his head against his left hand, which grips a crumpled piece of paper. The lighting emphasizes the puffy, wrinkled skin under his eyes and the stubble that is just beginning to appear on his chin. Freund’s portraits also recall nineteenth-century photography’s technical limitations. In the late 1930s, color film required sitters to pose in front of the camera for an extended period of time. This process recalls the prolonged exposure times of the mid-nineteenth century that shaped the languid poses and listless appearance of the sitters.

Freund’s thesis on the history of photography can help us understand how these portraits visualize her own historical circumstances. She begins her thesis by stating, “Each moment in history has its own form of artistic expression, one that reflects the political change, the intellectual concerns, and the taste of the period.” More than a simple connection between artistic form and context, Freund’s argument emphasizes the convergence of a certain kind of photographic technology and the self-consciousness of a certain group or class. Nineteenth-century cartes-de-visite, for example, crystallized the ambitions and status of the bourgeoisie. In his review of her study, the critic Walter Benjamin praised Freund’s efforts to relate the development of photography to the social structure at the time of its emergence. This approach, he writes, “amounts to determining a distinctive capability of the art work—namely, its ability to make the period of its production accessible to the most remote and alien epoch—in terms of the history of its influence.” This approach emphasizes the portrait’s ability to communicate the identity of a community to its audience, both present and future. As Nadar’s portraits made the bohemian community of nineteenth-century Paris accessible to Freund, she attempts to make her own historical conditions accessible to us in the future. And yet, what if that historical context is defined by uncertainty and the threat of fragmentation? How might photography register such uncertainties associated with the conditions of exile?

Although autochrome photography was invented by Auguste and Louis Lumiere in 1907, this process was not widely used until the late 1930s due to its prohibitive cost. Autochrome photography materializes the fragility of Freund’s imagined community. Its compositional effects muddle the psychological presence of the sitters. Rather than providing vivacity, color in the portrait series often complicates the viewer’s access to the sitter’s psychology. In Freund’s portrait of Jean Cocteau, the artist’s spindly fingers, clasping a cigarette, rhyme with the large red hand hanging on the wall behind. No doubt included to reference Cocteau’s Surrealist interests, this bodily fragment also functions to frame his face. And yet, the bold red of the hand and its rhyming with his bony fingers below competes with Cocteau’s face as the focus of the photographic composition. His blanched complexion and its off-centered position downplay the importance of the face in the portrait, thereby limiting access to his identity.

Other portraits intervene in the face’s communication and connection with its audience. After developing a friendship while they both studied at the Bibliotheque Nationale, Benjamin became one of Freund’s first sitters in her portrait series. Freund depicts Benjamin with his fingers stiffly touching his forehead. Besides visualizing the intellectual intensity of the sitter, this gesture interferes with the connection between the sitter and the viewer. The hand casts a shadow over half of Benjamin’s face, obscuring the face’s ability to clearly convey information about his identity. In her portrait of James Joyce, the writer’s thick glasses distort the appearance of his eyes and prevent us from meeting his gaze and reading something about his interior self. The monocle that Joyce holds at his chin draws our attention away from the face and distracts from attempts to connect with the sitter. If a community is based on dialog and interaction, then the interventions of color, shade, and lighting perform the fragility of the communal ties uniting this group of intellectuals.

Community demands a degree of intimacy and dialogue among its members. Freund’s presentation of her portraits as a slideshow emphasized photography’s role as not just a depiction of community, but as a way of staging such a dialogue between portraits and viewers. And yet, the composition and tonal qualities of Freund’s portraits do not allow such a dialogue to fluidly take place. The first public viewing of the portraits established the series as a rather ethereal collection. Although Freund claims that her reason for projecting the portraits rather than printing them was purely financial, these technical limitations, and the qualified possibility of color photography, enacted the conditions of exile that the photographer experienced. Each portrait was projected temporarily on the wall, and the phantasmagoric display of the portraits reflected their precarious status as members of a temporary community. As a projection, the members of this community appeared without material grounding. This slide show, brought about by the technical limitations of color photography, also enacted a moment of self-awareness. Through the flickering glow of the slide projector, audience members would have been presented with a community to which they belonged that vacillated between presence and absence. While presenting each figure as part of a community, the portraits also complicate the viewer’s ability to establish connections with individuals that such a community requires.

Once she immigrated from France to Argentina in 1940, Freund never again produced such a sustained project in color. Because of its sole connection to Paris in the late 1930s, then, this series of portraits evokes nostalgia about the intellectual community it creates. Besides stemming from my admiration for the cultural contributions of the members of this imagined community, this nostalgia could also be part of the crisis about the future of democracy and our planet in the twenty-first century, a crisis that only seems matched by what Freund and her sitters experienced eighty years ago. These portraits traffic between the nineteenth century, the 1930s, and our present in the twenty-first century, and compel us to think about what can be known about the immediate future at a particularly charged present. I look at these portraits and think about what happened in the following years. How much did they know of what was to come? How much did they let themselves hope things would be different? How much can we hope for our own future, now?