An End, Always Happening

In the hyperbole of “apocalypse,” in the rhetorical design that anticipates a time predicted forever, a poem that meditates on the end of the world situates itself somewhere between prophecy and historical memory. An end has been ongoing—and changing—since the first mention of the end. This end is prophesied as a turning, which is no ending nor a beginning, but an endpoint always happening. W. B. Yeats writes in a famously apocalyptic 1919 poem, “Surely some revelation is at hand; / Surely the Second Coming is at hand.” What Yeats notes to be surely-at-hand happens in the experience of the poem, at the precipice of something like real life, in the formal pressure that suggests we must imagine how this moment plays out, in real time. Shortly after, in section three of “The Waste Land” (1922), T. S. Eliot’s seer Tiresias is rendered to straddle the past—“I who have sat by Thebes below the wall / And walked among the lowest of the dead”—and everything happening now, in the time it takes to read the poem, in the sterile anticipation that something might be anticipated “at the violet hour, the evening hour that strives / Homeward.”

The end has been ongoing, but changing. Two decades after Yeats wrote “The Second Coming,” in 1944, the year of the Warsaw Uprising, Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz wrote his now widely-distributed poem “A Song on the End of the World.” Here, the end of the world is unextraordinary—that is, if one reads “The Book of Revelation” or Yeats’ poem too literally. The ending continues as scheduled: “On the day the world ends / A bee circles a clover / A fisherman mends a glimmering net.” This first sentence of the poem, lineated by clause, orders events as if nothing could disrupt their happening. Because if one anticipates specific images from their apocalyptic vision, this poem imagines, they will be wrongfully surprised: “And those who expected lightning and thunder / Are disappointed. / And those who expected signs and archangels’ trumps / Do not believe it is happening now.” With the underwhelmed “disappointed” accentuated so tangibly in the line, one realizes these deniers could never know how to see a non-hyperbolic end, symptomatic of the fact that it has been ongoing forever. The poem ends with another ordinary recognition, the person Milosz imagines equipped—if one could refer to these figurative resources as equipped—to simply know what is happening now, in this present:

Only a white-haired old man, who would be a prophet

Yet is not a prophet, for he’s much too busy,

Repeats while he binds his tomatoes:

There will be no other end of the world,

There will be no other end of the world.

This final doubling almost reaches an incantatory tone, like a song—but before the chant can be heard, the old man states his observation, a matter of fact. There is nobody to enchant, to convince. What has been ongoing, what here has been turning, will not happen again.

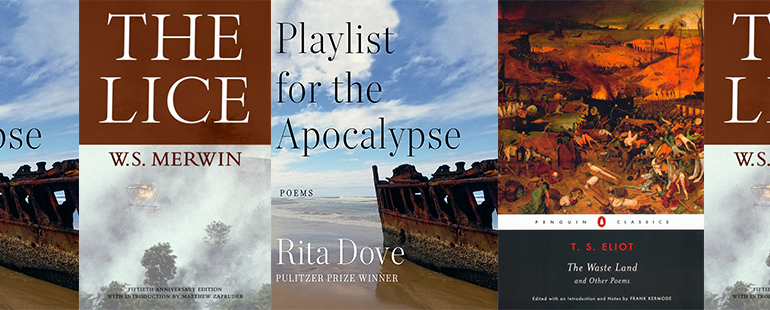

A great poet of endings, W.S. Merwin, would publish his popularly apocalyptic collection The Lice (1967) two decades after Milosz wrote “A Song on the End of the World.” Now his most widely read book (which was reissued by Copper Canyon Press in late 2017), The Lice responds to American cruelty during the late sixties and the Vietnam War. In the poem “An End in Spring,” the indefinite repetition of ending marks everything lost in that ongoing process of turning and turning: “It is with the others that are not there / The centuries are named for them the names / Do not come down to us.” Because these names are not passed along—because they are grouped together as an indefinite whole, understood only by how they’ve been forgotten—The Lice devotes itself to memory during these catastrophic, revelatory years. When Merwin passed in 2018, two poems from The Lice were passed around: “For the Anniversary of My Death” and “For a Coming Extinction.” The latter poem, addressed to a gray whale (or, because the poem begins without an article, the species at large), remarks on illegibility, on the impossibility of predicting in what ways the end will continue: “I write as though you could understand / And I could say it / One must always pretend something / Among the dying.” If this is true, if “one must pretend something among the dying” as Merwin writes here, does one also understand the figurative account of extinction as a form of “pretend,” a performance animated by the experience of reading the poem? Perhaps the poet’s hypothetical depends on his culpable expression in the face of extinction; the persona reciting this poem includes himself in the “we who follow you invented forgiveness / And forgive nothing.” The poet is human; the speaker of the poem is a representation of human—the poem confronts its shame that many extinctions have already happened and, following the gray whale, will continue.

Last month Rita Dove published Playlist for the Apocalypse, her first collection of new poems in twelve years. The category of “playlist” seems rightfully like artifice: are we on shuffle, or is this sequenced to sonically enact the apocalypse we experience, we remember, we anticipate? In the sequence “A Standing Witness,” individual poems respond to—or to borrow from Dove’s vocabulary, serve as a “testimony” for—moments of turning, an end extending beyond itself: 1968, The Age of Aids, 9/11, Trump. A poem from that sequence, “Limbs Astride, Land to Land,” followed by the subtitle “Eighth Testimony: The Berlin Wall,” playfully conducts our spectating, our own witnessing: “Don’t brood or marvel, just enjoy the music, / death strip lit for photo ops, bananas for all— / History doesn’t cough up triumphs easily.” One function of Playlist for the Apocalypse, if one follows the metaphor, is to “enjoy the music”; another is to participate in the experience that these poems enact, our own contribution to the playlist. Likewise, in the final poem from this sequence, “The Sunset Gates,” readers are asked to observe beyond their own sense of what has happened and what is happening and what might continue to happen:

Come visit! Ascend to the crown and gaze out

at the nation I’ve sworn to watch over.

I stand ready to tell you what I have seen.Who among you is ready to listen?

This question is partly a challenge, a call to action. You might listen, sure, but who among you is prepared to dance, or, as Dove later choreographs, in the poem “Borderline Mambo,” “Mambo, for instance, / if done right, gives you a chance to rest: one beat in four. / One chance in ten, a hundred, as if / we could understand what that means. Hooray.” When designing a playlist for the apocalypse, inscrutability makes that experience of anticipation even more intense; Dove writes in the same poem, “Of course it matters when, even though / (because?) we live in mystery.” Because the end has been ongoing, one knows it will continue but not what it will look like, nor what that means for the future.

Today a poem is not exactly a song: a song has the benefit of musical accompaniment, melodies and harmonies that pressurize what might, in other ways, be felt in the formal composition of the poem itself. Yet for a long time, a poem has had features that have been described as musical—rhythm, patterns of speech sounds made by words recited in a specific order, refrain—and this descriptor is a metaphor for what one has learned to hear while listening to music. Just as Milosz writes “A Song for the End of the World,” Rita Dove writes “Blues, Straight” and translates Goethe’s 1776 “Wayfarer’s Night Song,” the final poem in her collection: “Just wait: before long / you, too, shall rest.” What do we mean when we describe a poem as musical, or as a song? I suspect the answer will mean many things for many people, each with different relationships to what poetry can do or has done, each with different relationships to the traditions and historical contexts through which they write—though the common language one finds here comes from the most basic observations. A poem is like music, a book of poems is like a playlist for the apocalypse—they both have ways of enacting a physical and temporal experience through their structural and formal patterns. One reads a poem, and that’s an experience in time organized by specific words in a specific order; one listens to their favorite song, which is also an experience in time. Perhaps it’s enough to say that experience stretches the end a little further into the future, or perhaps for some it does not. To recognize how long we have considered “some revelation at hand” points to the act of anticipation and the effect it has on memory; so long as one anticipates, so long as “the apocalypse” continues to change, the end also accumulates into something illegible—if not for how one experiences it in real life.