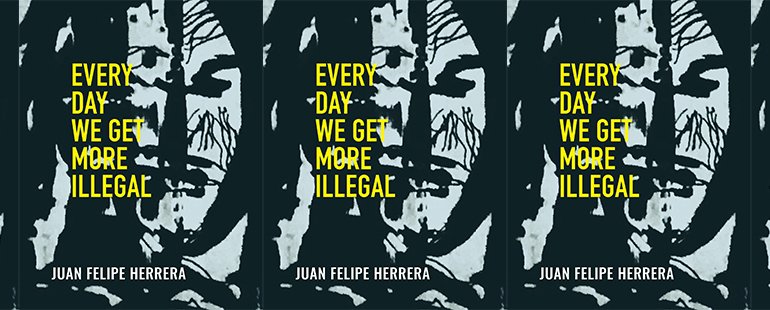

Attention in Every Day We Get More Illegal

Juan Felipe Herrera’s poetry collection Every Day We Get More Illegal, published last October, begins with a dedication “for all the migrants, immigrants and refugees suffering from the border installations within the United States, at the border crossing and throughout Latin America. / for a borderless society and world, made of relentless unity and kindness and giving.” The poems that follow persist in this attention to border-crossings, the looming wall undergirded by a war machine, and the violence upon violence inflicted in its far-reaching shadow. The poems depict deportations, economic pressures, the threat of nuclear disaster. They represent the indignities and injustices experienced by Mexican, Central American, and South American migrants and the collisions and collusions that are commonplace in twenty-first-century transnational life.

The representations are explicit and insistent. They depict, as Herrera puts it in the poem “Don’t Push the Button,” “the massacres the massacres so many massacres in plain sight.” They speak, as in “Roll Under the Waves,” of “ men lying face down forever and women / dragging under the fences and children still running with / torn faces all the way to Tucson leathery and peeling,” and of “vigilantes with skull dust on their palms.” They voice howling pain, and they confront readers with what Toni Morrison called the unspeakable and unspoken, as in the early poem “You Just Don’t Talk About It,” which is a breathless unpunctuated cry that carries on from margin to margin for nearly two full pages. “Lissen,” it begins, “you just don’t”

talk about it the rape the endless scrubbing washing self

lacerations the never ending self-whipping the deep down

smoldering stone trauma growing up crooked tree growing up

silence ocean storm

The list of the untalked-about includes “the suicided the / hanged w/a bedsheet of nothing in the cell of nothing.” It includes “the young with no-lunches and the / no-books and the / no schools,” colonially-introduced addictions and plutonium in food, the “pesticide skin” of agriculture workers, oil pipelines, and “lands you stole from under our feet.” It speaks of an endless array of domestic and other servitude, “the rape the assault / the segregation the jailing the deportations upon deportations.” At its very end, the poem speaks of “The starving ones curled up on the freezing detention corners” and concludes, damningly, by repeating: “and you — you / just don’t talk about it.”

I’ve written at length elsewhere about the ethics of representation and the ethics of attention in literature, about the ways literary texts represent suffering people—in both the aesthetic and the legal sense—and ask of their readers careful, close attention that matters in the embodied world. Herrera’s book confronts me again with this dynamic, nudging me to attend, asking persistent questions: Am I paying attention? Are my friends? When is the last time we talked about children in custody at the southwest U.S. border? Many of us talked about this outrage in 2018. The family separation policy has since ended, but have those children been reunited with their families? Is the new administration doing better now?

A quick internet search turns up news stories from the past six months about decreasing and then increasing numbers of unaccompanied minor migrants, of the U.S. and Mexico releasing asylum seekers in remote Guatemalan locations. I would not have heard this news had I not gone looking. What else have I forgotten and missed in the rapid shifts from outrage to outrage over the past three years? What are we missing today?

Just weeks ago Hurricane Ida wreaked havoc in the South and Northeast, and while recovery efforts are ongoing, national and international attention has waned. These stories of crisis and forgetting pile up. Who is looking after the remaining refugees in Afghanistan? What is happening with governments in Ethiopia or Lebanon? How are people in Haiti rebuilding this week? How many World Trade Towers worth of Americans have died this month from a virus now mostly preventable with a safe and effective vaccine? What’s the current rate of vaccination in West African nations? In Thailand? In Peru? Where are forest fires burning today? Have folks moved on now from the hysterics about Critical Race Theory? Are women receiving the healthcare they need in Texas, and what’s the long game to make sure they do?

No human person can care about every disaster and injustice and sorrow. No one can keep up with all the news, hold all the pain within one pounding ribcage. No one can know all the answers, contribute to all the solutions. We are not built for this global scope. The past century’s rapid technological developments have run out ahead of us, spun us into frenzies.

But Herrera’s poems don’t let their readers assume that the answer to this overwhelm is to disengage. Instead, they pose the question: What forces determine where our powers of attention go? Why is it the case that “You Just Don’t Talk About It”? What flows of power and privilege, economic pressure and media focus, determine which causes we give our hearts to on any given week or day? What forces pull us to cross borders? What forces pull us to build walls? And what does it mean to bear witness to these realities in poems that persist in time as history unfurls with dizzying velocity?

Of course, not everyone forgets. And for those who live the realities Herrera represents, there is no choice but to attend to the pressures of their own situation. His poems address both the “you” who just don’t talk about our reliance on migrant workers and the deadly pressures of American international policy, and also the “you” of migrants, immigrants, and refugees, whom he invites into community in the book’s final sequence, titled “come with me.” These addressees already know their own pain; instead of reflecting it back to them in this last section, Herrera welcomes them toward something more like healing. In sparingly printed pages that offer both English and Spanish versions of their lines, Herrera promises to be writing “with one letter the story of our lives”—“con una letra historia de nuestras vidas.” In both languages he calls for collective dancing, play, and memory, balancing the book’s focus on suffering with a parallel focus on cultural persistence and ancestral wisdom, affirming communal identities.

This focus on human tenderness is also threaded through the collection in a series of six brief numbered poems called “Address Book for the Firefly on the Road North,” which appear as section breaks. The “Address Book” poems offer travelers gentle observations and advice: “here a river — you can stop / you can bathe & rest.” Such soothing words of guidance welcome the imagined northward travelers, and their interruptions offer a persistent reminder of the collection’s dual communities of address. But they also ring out in heartbreaking resonance with the haunting poem “border fever: 105.7 degrees,” which arrives two-thirds of the way through the book. In this poem’s epigraph, Herrera bears witness to Jakelin Amei Rosemery, age seven, and Felipe Gómes Alonzo, age eight, both of whom were from Guatemala and both of whom died in December 2018 in the custody of Customs and Border Protection. In the poem, a border guard questions a crying child, insisting they hear “not screams” but “a symphony”—a damning indictment of aestheticized suffering. One voice describes “a girl up ahead / made of sparkles” while another asks for directions. The brief poem disorients with disembodied voices, ending with the image of “a lost flame a firefly / dressing for freedom” and asking “where did she go.”

This firefly image links the children whose lives were snuffed out by a lack of attention to their desperate needs—and more broadly by the “always-war” of the border, in the words of the sequence “[interruption]”—to the “Address Book for the Firefly on the Road North” poems. Four of these poems precede “border fever: 105.7 degrees,” and the fifth firefly poem follows on the facing page. On subsequent readings of the book, these firefly poems stand out as repeatedly re-centering the most vulnerable of all, the children with their flickering life-lights, offering them guidance on their journey north and the tenderness of direct address. They bring our attention back, time and again, to the irreplaceable human lives in the crosshairs of global forces we so easily abstract.

To bear witness to Jakelin Amei Rosemery and Felipe Gómes Alonzo in the book’s firefly motif is not to render their screams symphonies. Herrera does not shrink from depicting the full horrors of the American imperial project, its threats to body and soul. But even as the collection confronts white American readers with these representations of pain and death, it sings welcome to the children on their journey. “Address Book for the Firefly on the Road North #4” reads, in its entirety:

ancestors

passed these trails

their designsoffer kindness to the timeless trees

they recognize you

We see you, the poems seem to reassure the firefly—or the lost children—on the way. Others have come before you. You are by no means unaccompanied.

As a white settler American, then, the poems ask me to pay attention to both the horrifying violence and also the love and care in Herrera’s spare lyrics addressed to his community and to the “lost flame,” the “firefly / dressing for freedom.” Every Day We Get More Illegal suggests that in the cacophony of global concerns, ever-expanding in a world divided by borders and injustices, memory matters. Poetry can represent both widely shared experience and specific names and dates that persist on the printed page, sparking recollection and something like caring in readers who later pick up the book, no matter how much time has passed, and confronting some of us not just with what—and who—must be remembered but also how much we’ve forgotten, how much is left to do.

Herrera’s book doesn’t resolve the problems of novelty-driven news coverage or the finitude of human minds and hearts, but it invites a kind of attention to poems that can matter for both the remembrance of the lost and the survival of the living. Every Day We Get More Illegal suggests that to sustain the kind of attention that leads to embodied care, to structural justice and community support, we will need both rage and dancing, ranting indictments and ancestral wisdom. Outrage and tenderness are not competing forces but mutually sustaining. To bear witness to Jakelin Amei Rosemery and Felipe Gómes Alonzo requires both shouting down the forces of military and economic power that killed them and also singing them sweet lullabies to help them—and others—find the place they were looking for.

This piece was originally published on September 20, 2021.