Authenticity and Artifice in The Candy House

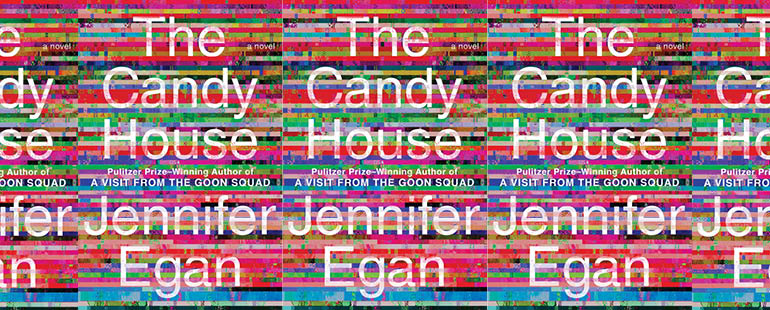

When I first read Jennifer Egan’s Pulitzer-winning 2011 novel, A Visit from the Goon Squad, in the spring of 2017, I was mesmerized. Living in Budapest, Hungary, where I was starved for English language books to read, I had begged my family to bring some with them when they visited. My older brother had just finished A Visit from the Goon Squad and brought his copy for me; I opened it soon after and was immediately pulled into a two-day fever dream of reading and rereading. Twelve years later, Egan has gifted readers worldwide an equally dazzling sequel(ish) to that contemporary masterpiece: The Candy House.

Where A Visit from the Goon Squad is concerned about the contemporary experience of time, The Candy House, using some of the same characters, thinks about authenticity and artifice in this era and beyond. Its title comes from a motherly lecture: “Nothing is free!” we read. “Only children expect otherwise, even as myths and fairy tales warn us: Rumpelstiltskin, King Midas, Hansel and Gretel. Never trust a candy house! It was only a matter of time before someone made them pay for what they thought they were getting for free. Why could nobody see this?” The gist of this reprimand is simple—if it’s too good to be true, it’s probably not true. At its most fundamental level, then, The Candy House is about stories, about how humans are inclined to shape information into narrative.

The novel’s characters turn story tropes into algebra, look for patterns in anthropological research, and, most notably, upload their memories to something called Own Your Unconscious. There, you can relive your own memories and access other people’s. Born of Bix Bouton—a minor character in A Visit from the Goon Squad made tech giant here—Own Your Unconscious stems from Bix’s own “frustration at the inaccessibility of his memories,” an inability to fully recall an incident during a friend’s last day in particular. The intention here seems good, but the technology is, indeed, too good to be true—a candy house holding astronomical consequences for individuals and society as a whole.

We do see Own Your Unconscious serving characters well: Bix uses it with his family, playing “certain sections of his consciousness for [his son] Gregory and his siblings, usually to illustrate a point or teach them a lesion—although, lately, it had occurred to Gregory that maybe what their father wanted was just for them to know him better.” Here, as with other families in the novel, having access to a family member’s memories can draw people together; something can be shared that typically remains inaccessible. Own Your Unconscious, too, can bring healing to families that are apart and reconciliation with those who have passed away.

For one daughter, Charlie, seeing her father’s unconscious brings her a chance to view a more loving side of him. Charlie watches Lou’s memories of a Northern California commune in the 1970s, a place that sparked his desire to start a career in music production. Her access to these memories sparks something in herself—an opening of the world: “my father’s consciousness seemed like more than enough—overwhelming, in fact—which is maybe why, over time, I began to crave other points of view.” Charlie’s half-sister, Roxy, has a similar experiencing to using Own Your Unconscious to connect with their father. At first, viewing his memories is a terrible and overwhelming experience of information overload. Yet uploading her own unconscious to the collective brings Roxy a sense of connection with him that was never achieved in their tenuous and distant real-life relationship. “Her father is there, somewhere,” we read. “Roxy feels their memories conjoin at last, like their two arms swinging on that long bright night. The whole of her past whirls through a portal and vanishes onto a separate sheet of graph paper.”

Many also use the Collective Consciousness to solve mysteries, both personal and structural: “Who was that kid who beat me up? Where is that teacher who touched me? Who killed my friend? Or, more hopefully: What happened to the guy I shared a beer with at Cafe Trieste in the 1990s? Who gave me that back massage during the Green Day concert in Golden Gate Park?” Yet as another character, Chris Salazar, remarks to Roxy, “it never stops there. The collective is like gravity: Almost no one can withstand it. In the end, they give it everything. And then the collective is that much more omniscient.” Own Your Conscious is a true candy house, a promise that is too good to be true. Giving away your memories brings tangible payoffs, but leads to unconsidered consequences. Is Own Your Unconscious—is the realm of hyper-connection we live in— then good or bad? The Candy House refuses to decide.

It’s all a question of framing. How do we turn a mass of information, unconscious and impressionistic, into meaning? The Candy House makes it clear that what results is both arbitrary and decisive. So many characters in the novel overlap and interact with those in A Visit from the Goon Squad that it suggests the constellation of connections in the world Egan has built stretches far beyond these two covers; after reading from the perspective of one character, we later encounter that same character as a minor player in someone else’s story—Chris Salazar plays D&D in Roxy’s section; narrates his own chapter; then appears later, in a chapter composed entirely of emails, as the architect of a communication app for those who want to remain off the grid. In The Candy House, then, it’s the mind of the reader that becomes something like the mass unconscious—a collection of many perspectives and stories. Reading a novel, after all, is one form of inhabiting another perspective than our own, akin to recalling someone else’s memories.

Yet in a novel we have the benefit of a filtered narrative. “Knowing everything is too much like knowing nothing; without a story it’s all just information,” Egan writes. “So let us return to the story we began.” Her sprawling, hyper-connected novel thus points to its own limits, showing us just how much filtering and framing goes in to making narrative work. The Candy House, then, tells us something about what we might call the power of story: turning information into narrative, whether via algebra or anthropology or aphoristic manual, is what people do.

Right before the novel ends, Bix’s son Gregory, a fiction writer who has been unable to write (or function, really) since his father’s death, recalls what narrative is for. It’s an odd moment because there’s a narratorial intrusion: “Only Gregory Bouton’s machine—this one, fiction—lets us roam with absolute freedom through the human collective.” The narrator here steps in to remind us where we are—at the end of a novel, reading fiction—and what we’re doing. We’re in a different kind of Collective Consciousness here, we’ve been roaming free through it for hundreds of pages. And this one is much easier to own.