The Artist as Writer

In 1973, Kusama Yayoi returned to Japan from New York and began experimenting with poetry and fiction.

Please note that orders placed between February 1-February 17 will not be shipped until February 17. Thank you for your patience.

In 1973, Kusama Yayoi returned to Japan from New York and began experimenting with poetry and fiction.

Studies with children have directly connected reading fiction with the development of empathy, but things get messy when we look at how empathy actually works in the real world. Who are we empathizing with, and who are we leaving out? And will it really lead to moral action, or is it just a sentimental entertainment?

Culture shock is central to Tawada Yôko’s subject matter: her characters tend to be travelers of one kind or another—mail-order brides, bewildered exchange students—forced to wander in the gap between languages, where the meaning of ordinary daily experience turns slippery and weird.

Mizumura Minae’s career has been focused on exploring this question in formally inventive ways that often incorporate her own cross-cultural autobiography. In the process, she has managed to transcend the specifics of her own personal story, creating a body of work with incisive things to say about the individual’s relationship to language, culture, and history.

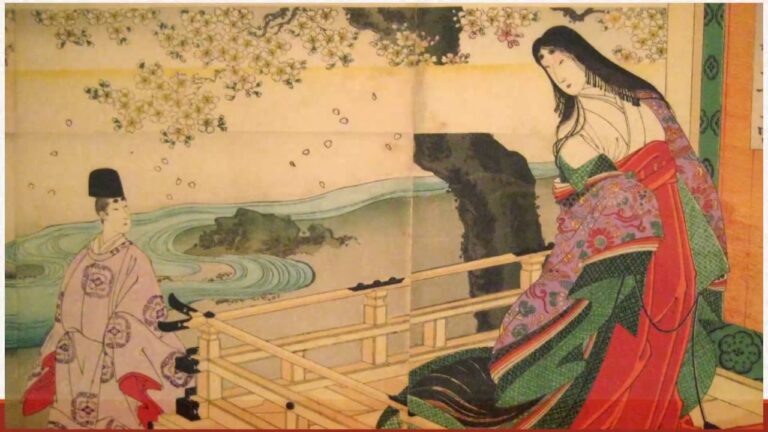

Sei Shonagon’s book, completed in the year 1002, interrogates power and powerlessness through the use of formal hybridity, offering itself up as an unexpected progenitor of our current literary scene.

We in the English-speaking world are used to the idea that we apprehend Genji only dimly through translation, as if through a scrim, watching shadows. So why then have two Japanese sisters, both well-known poets, spent years retranslating an Edwardian English translation of the novel back into Japanese?

In his 1961 novella, Kawabata takes the idea of the male gaze and makes it concrete, a laboratory in which to test our preconceptions about masculinity and male privilege.

No products in the cart.