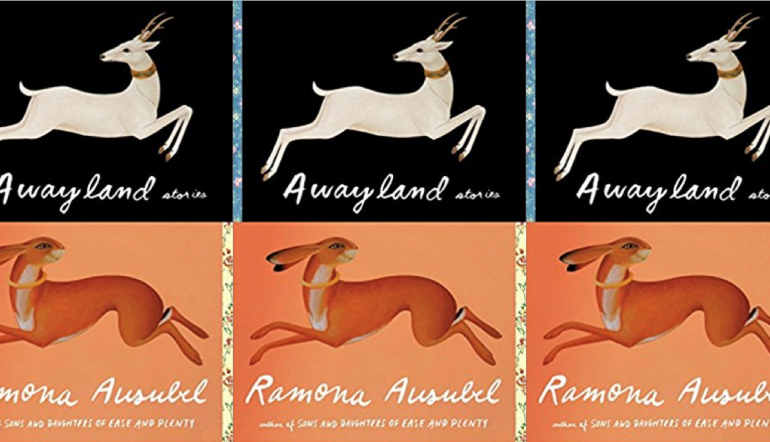

Awayland by Ramona Ausubel

Awayland

Ramona Ausubela

Riverhead Books | March 6, 2018

Ramona Ausubel loves to write fiction that lives in the space between the real and the magical, often using the form of the fable to shine light on the real. Awayland, her newest story collection, features eleven stories, and a reader of Ausubel’s prior work (No One Is Here Except All of Us, A Guide to Being Born, Sons and Daughters of Ease and Plenty) will be familiar with the themes of family, loss, and an ever-present search for something more. The title of the collection sets that search in motion with the creation of a different world, and the stories are collected within that into distinct groupings: Bay of Hungers, The Cape of Persistent Hope, The Lonesome Flats, and The Dream Isles. To read an Ausubel story is to escape to another place, and yet it’s a place that’s familiar to us, one that’s filled with longing, regret, and love.

Ausubel often uses humor to highlight the differences between the magical and the real. In “You Can Find Love Now,” a delightful, short piece that was originally published in The New Yorker, Cyclops fills out an online dating profile: “I can’t ski. I should be better at basketball than I am. I don’t eat vegetables. But my eye is blue, and it’s pale and beautiful.” In “Do Not Save the Ferocious, Save the Tender,” three men are shipwrecked, and then one of them encounters another being: “It was when he got close that he saw a face. ‘Oh,’ he said, because what do you say when a mermaid washes up?” It’s great fun to watch Ausubel’s enormous imagination at work and to share the joy that emerges from her writing.

That said, the strongest, and most haunting, stories in the collection are those that make the magical real as they examine loss. “Fresh Water from the Sea” is the story of a woman who is actually disappearing. Her daughter flies to Beirut to be with her, and the story becomes the tale of their last days together, and the daughter’s thoughts of her life after her mother is gone: “The girl could already feel the empty space forming around her mother, and its gravity. She knew she would circle it for the rest of her life, orbiting that absence.” In “High Desert,” a woman’s daughter drowned years before, and even now, when she sees girls in the street, “The woman studies their faces, just like she has studied every face of every girl in case it is her girl, in case her daughter has found her way home.”

Pregnancy, motherhood, and complicated parent-child relationships form a backbone of sorts to this collection. In “Club Zeus,” one of the longer stories, a teenage boy goes to work at a resort on an island. He sees a man drown and he thinks: “I’ll bring him home with me, give him to my mother to share with me—though it would be kind to spare her, to tell her only the easy stories of sun and sea, or kebabs and soft breads, I will poison her with this death and upset her peace, because sometimes a person deserves company.” In “Template for a Proclamation to Save the Species,” a mother thinks about what she will teach her new baby:

How to get on the bus without buying a ticket; how to pay for one movie and see three; how to fight with your father so that you always win; how to ensure maximum darkening of the skin in the sun; how to find your life’s horizon—that place just far enough in the distance to keep you moving forward but not so far as to be discouraging.

There is almost always tenderness here, but it’s mostly unsentimental, reflecting the true nature of living with others in this world. The only story that feels perilously close to the sentimentality of an O. Henry story is “Remedy,” about a couple who have decided to surgically swap their hands.

Two of the stories are linked: “Fresh Water from the Sea” is told from the point of view of the daughter while “Mother Land” is told from the point of view of her sister. The stories don’t follow directly after one another in the collection nor do they cover the same events, and it takes a beat or two to recognize the connection. There’s such pleasure, as a reader, in discovering the links between them, of seeing how and where the two points of view converge and break apart. It was disappointing, in fact, not to have more of the stories connected in this way, even while central themes indirectly link them all.

One of these ongoing tropes is the act of writing. Just as the use of fables and magical realism make us aware of the artifice of fiction, Ausubel often refers to the craft of writing, a meta-fictional wink at the reader. In “Template for a Proclamation to Save the Species,” the mayor of a small town sets up a prize for the first baby born on Lenin’s birthday. It’s a long nine-month wait for the winner, and Ausubel writes, “But the mayor had not thought of how long the middle would feel. He had only considered the beginning and the end.” What a painfully familiar thought to any writer. And in “The Animal Mummies Wish to Thank the Following,” the dog mummies are confused about where they were buried: “Is there some through line, a theme, they do not understand?”

Ausubel’s prose is assured and often lovely, descriptions and insights presented in new and different ways. In “Departure Lounge,” a woman thinks of the fact that she no longer sees her ex-boyfriend’s parents: “Good people, people you truly like, get shelved that way. You inherit them for a while, but they are not yours.” And the woman notices that “The street was filled with jacarandas, bare branches haloed in the purple fog of flowers.” The climate in Africa makes the protagonist in “Mother Land” miss her home: “It rained all night, the kind of warm rain that made Lucy feel the distance she had come. Even in summer in California, the rain was cold.” California love threads its way through many of these stories. But no matter where you call home, you’ll find much beauty and insight throughout this collection.