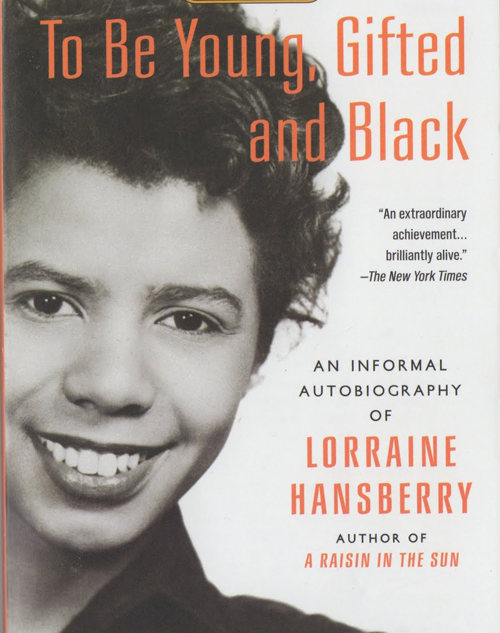

Be Recorder by Carmen Giménez Smith

Be Recorder

Carmen Giménez Smith | August 6, 2019

Graywolf Press

Amazon

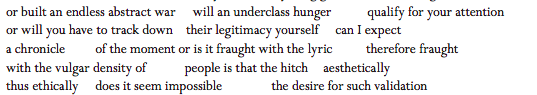

Before its poems even begin, Carmen Giménez Smith’s newest book offers the reader its imperative. Be Recorder, its title demands. In many ways, its poems suggest that we can’t help but do just that: absorb and reflect what we witness, what we’ve experienced, those we brush up against, whether that contact is good or bad. The book presents the construction of the self as a complex process that we ourselves participate in but only alongside myriad others. Race, class, immigrant identity, gender, family, and all the ways those are reflected back at us by individuals and larger culture are recorded, inscribed on the self in ways that the speaker finds, by turns, comforting, disturbing, disorienting, sad. At the same time, the collection, and especially “Be Recorder,” the long poem that makes up more than half the book, is an appeal to readers to observe, to “break free and record,” and, in fact, to do more than just recording passively—to “be recorder,” to embody witness. “Have you made anything good with our outrage,” asks the title poem,

Giménez Smith’s moral imperative—to witness and act as enduring evidence of what you’ve seen—descends into a complication the speaker doesn’t seem entirely in control of. What does it mean, the poem asks, to filter a moment (as a poem does) through a particular perspective, through “the vulgar density of people”? We must witness (“break free and record”) while also investigating what witnessing means for us, seated as we are in our particular selves, in our particular bodies.

Giménez Smith nestles the book’s sprawling, associative, surreal title poem amongst the clear, often incisive ones of the other two sections of the book. The book’s first poem, “Origins,” works in a mode that is entirely different from the title poem’s but that lays the groundwork for the complication that “Be Recorder” addresses. “People sometimes confuse me for someone else they know/because they’ve projected an idea onto me,” the poem begins. “I’ve developed/a second sense for this—some call it paranoia, but I call it/the profoundest consciousness on the face of the earth.” That projection is familiar to the speaker in that recognizing it is a gift:

In the moments when the speaker experiences racism, she is overwritten, her face, her self, elided by the assumptions that some other provides. She remembers a teacher who confused her with another graduate student “with not even/brown skin, but what you might call a brown name.” The experience is painful and leaves the real person, who the speaker actually is, raw, abraded by rubbing up against who people think she is. The pain of this “took years to overcome, but I got over it and here/I am with a name that’s at the front of this object, a name/I’ve made singular, that I spent my whole life making.” The poem’s movement speaks to all of the complications of making that name, of building an identity for yourself. The speaker defiantly creates her self in the face of all that would create that self for her, while also having to confront the ways that the racism she and her family have experienced has shaped who she is, has given her that “profoundest consciousness on the face of the earth” and also “that sting” of elision.

The poems in Be Recorder zoom in toward and out away from the speaker as they consider the ways that the self is built or chipped away. In the last poems of the collection, Giménez Smith thinks about the way her mother’s memory, and thus identity, is chipped away by disease, but she puts these poems next to ones like “In Remembrance of Their Labors,” which she writes “in remembrance of all the nosotros muffled by the clang of dishes and jokes about Latinos.” Both of these types of poems present an elision, both a loss of self. Each type of loss is rendered painfully, urgently, and vividly.

These sections of more narrative, crystalized lyrics help us approach the title poem, “Be Recorder,” which beats like a hidden heart in the center of the collection. The poem is remarkable, epic, and important. It inundates us with the often-uncomfortable realities of living in a time and place that bears down on the self and enforces conformity and adherence to white supremacist, sexist, and heterosexist values; xenophobia; and desperate capitalist consumption. “A monolith overshadows the animals,” the poem begins, “in their boxes stacked so corners stick/into corners of others for morale the animals/think about a next life while the monolith smothers/reality.” Though the poem feels, tonally, as if it depicts a terrifying dystopian future, it actually presents an abstracted picture of now, a time when the speaker—and, we might infer, us too—is “risen from foam/necessitated by colony sired in violence exported as luxury,” a time when “trifling bureaucracies/lodge…a vast/root” in us.

The chaos, dissolution, and bleakness of this vision of the world underpins the quieter, more narrative poems in the collection and is matched by the urgency of the speaker’s “revisionist chronicle”—her fantasy of a future in which “a cabal of my favorite womxn/run the show”—and her petition for us to “admit to our own complicity” and “release into the wound,” to “prepare to live tight and court danger… to stop buying/and watching… to turn hate/into light.” The vision presented in Be Recorder, then, isn’t completely bleak. Hope is seated in that active, astute, and vigilant speaker, who is capable of recording the monolith, deconstructing it, and reassembling it as a world that looks a little more like one we can bear.