Beasts of a Little Land’s Exploration of Survival

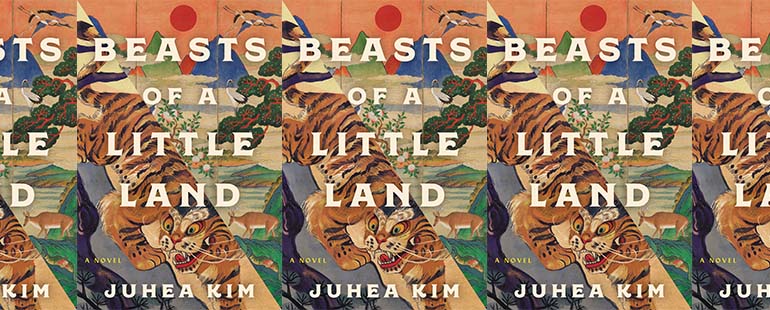

Juhea Kim’s debut novel, Beasts of a Little Land, out earlier this month, begins with the story of a hunt on a snowy mountain in northern Korea. The hunter is tracking what, from its paw print, he believes is a large leopard; he has run out of food for his family, and small game is scarce at this time of year. When the beast finally appears, however, he sees that it is a young tiger, not a leopard. Remembering what his father taught him years ago—Kill a tiger if you have no other choice. And that’s only when the tiger tries to kill you first—he lowers his bow and arrow and, empty-handed, begins his trek down the mountain and back home.

The hunter’s ethic is based on respect for the tiger’s power. As his father told him, “If you take a shot at the tiger too soon, you’ll only injure it lightly and make it more ferocious. Take a shot too late or miss, the tiger will be upon you before you finish blinking your eyes. A tiger can cross fifteen yards in a second.” Meanwhile, the occupying Japanese hold no such regard for the Amur tigers that at that time still lived on the Korean peninsula. They hunt the tigers for trophies and even for their meat, which “had become a fashionable delicacy on the tables of wealthy Japanese.” Power, domination, and the extraction of resources appear to be their ethics—and so Korea’s tigers do not survive Japanese rule in Korea.

Over the course of World War II, Japanese imperialism exhausts itself as well, in Korea and beyond. Beginning in the northern mountains in 1917 and concluding in Jejudo, an island to the south of the peninsula, in 1965, Kim’s novel tells about the years of Japanese rule in Korea—years of sometimes brutal oppression, starvation, and resistance—and its demise and aftermath. The characters include the hunter’s son, Nam JungHo, who becomes first a street ruffian and then a resistance fighter in Seoul and Shanghai; Jade and her adoptive family of courtesans in PyongYang and Seoul; Lee MyungBo, a communist resistance leader; his former classmate Kim SungSoo, a Japanese collaborator; and Yamada Genzo and Ito Atsuo, Japanese military officers, among others. Through the novel’s omniscient third-person narrator, we see what each of these characters is willing to risk or sacrifice, whether for survival or some other purpose. Some, like JungHo, believe “that life is not about what keeps you safe, but what you keep safe, and that’s what matters the most”; others, however, count their survival or prosperity above all else and are willing to sell out even their friends for their own benefit.

JungHo’s purpose is personal, romantic: what he wants to keep safe is Jade, whom he has loved since they were children. MyungBo holds similar views, but his purpose is principled rather than personal: Korean self-rule. As he prepares for the proclamation of Korean independence and mass demonstration on March 1, 1919, his onetime friend SungSoo questions this purpose. “What matters more, a titular independence, or actual prosperity? If you end up killing half the country in order to make it ‘independent,’ doesn’t that defeat the purpose of fighting? You act like you don’t care about death, but the whole point of this struggle is to live, isn’t it?” MyungBo responds, “You’re right, I don’t care about dying. But I don’t think our resistance is all in vain, as you do. . . . The purpose of our movement isn’t simply to avoid extinction. Its purpose is to do what’s right.” And “what’s right” is not an abstraction to him: he has in mind the “good, hardworking peasants, who have never done anything bad in their lives, because every single waking minute is spent trying to put some food on the table”—peasants whose land has been stolen from them. So in the wake of the demonstration, which ends with a crackdown, the death of hundreds, and the imprisonment of many others, including MyungBo, his view changes. He is still willing to take risks himself, but not to stake the lives of others for no gain, and he now sees unarmed resistance as futile. “Nothing could change without force in the face of such inhumanity,” he concludes, and he vows, if he survives prison, to “win back their freedom at any cost—life for life, blood for blood.”

Of course, violence, too, can be futile, as Yamada Genzo comes to see. A career military officer who over the course of the novel moves up through the ranks from Captain in 1917 to General by 1944, Yamada appears to be ambivalent about his commitments. As the narrator observes just before Yamada agrees to a marriage that he does not care about, neither for nor against, he “had discovered that how he should feel often differed from how he did feel.” As early as July 1941, he knows that the Japanese cannot win the war; for all their imperial voraciousness, they don’t have the oil, iron, rubber, or food to sustain the fight. With this reality so starkly clear to him, how he does feel again fails to match up with how he should feel, or how he once thought he should feel as a Japanese military officer. “You know, Atsuo,” he tells his friend Ito, “I’ve never really felt free. But in my youth, I thought that constriction was good, beneficial. I saw the world as a system laid out by intelligent and important people, and I was going to be one of them. But now I realize what a fool I’ve been. That system is nothing but that which brings destruction.”

And yet, Yamada keeps fighting, keeps playing the role he took up in his youth in a system he now sees as destructive, senseless. What else can he do? In the end, only death makes sense to him. Jade—who as a courtesan, dancer, and silent movie actress plays no important part in the system and has a disregarded intelligence—on the other hand, is only a girl when she clearly sees the underside of the system in which as a youth Yamada was so eager to participate. Her home in Seoul is near the ChangGyeong Palace Zoo, and one day JungHo helps her climb a zelkova tree whose branches extend over the zoo wall so that she can see the animals there, such as the elephant named Giant:

He was so large that even from afar, Jade could see him blinking his eyes as big as the palm of her hand. The crowd cheered and threw things into the enclosure to get his attention. Whether out of patience or stubbornness, the elephant gave no reaction, and soon the bored spectators left and were replaced by the next row. Some people cursed and spat into the moat, and others tossed him apple cores, but Giant still didn’t stir.

Jade thought that the creature’s suffering was all the greater for its strength and size; there was nothing tragic about a captive flea. She didn’t want to keep looking, and at the same time couldn’t turn around and leave it. She had been longing to see the world. Now that she saw what it was, she felt a creeping sense of nausea.

Seeing Giant at the zoo, Jade understands at once that the world is set up to produce suffering. Later she tells JungHo that Giant thinks all day not about food (as JungHo, himself accustomed to hunger, suggests) but continuously asks himself, How can I get out of here?

Like MyungBo, then, Jade perceives a longing for liberation in those whom the system has trapped. But unlike MyungBo, who was educated in Tokyo and is positioned to inherit his family’s estate, Jade has neither great power nor great wealth, and so she devises no grand schemes. Nor does she make grand pronouncements about her purposes or survival. “Why do I have to survive?” she asks of Ito in a chance encounter with him toward the end of the war. “I feel like there’s no meaning to it. The world is crumbling down, it’s becoming a more evil and dark place every day, and I have no one.” (“Fuck war, and fuck loneliness. Stay alive,” he responds before returning, in 1944, to his family home in Nagasaki, and it is remarkable how the novel manages to generate empathy even for one of its most loathsome characters, the self-satisfied collector of animal pelts and antiques; accumulating the products of destruction cannot save him from destruction.)

Though she may question its necessity or meaning, Jade does survive, in the meantime helping those whom she can help, such as HanChol, the rickshaw driver whose school fees she pays, and Dani, her adoptive aunt whom she nurses through her last days. Living as she does in the cracks or margins of the system is one way to survive the system—as perhaps, Jade learns, even the tigers have done in Korea, possibly finding a home in the Demilitarized Zone or in the mountains along the border between China and North Korea.