Blood at the Root of a Rural Georgia County

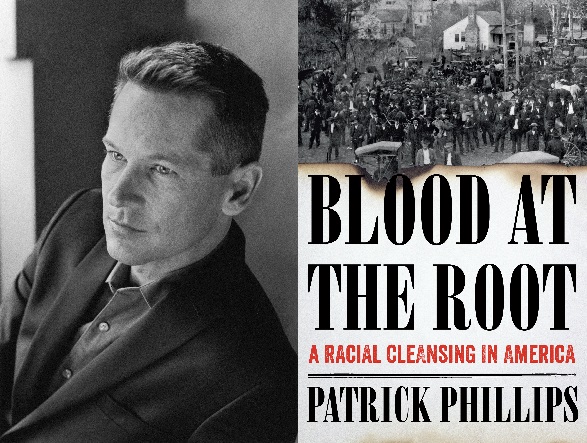

Photo courtesy of Marion Ettlinger

Thirty years ago, in 1987, Patrick Phillips was sixteen years old and lived with his family in Forsyth County, a rural farming community less than an hour’s drive north of Atlanta. He and his parents joined a march led by Civil Rights activist Hosea Williams marking the seventy-fifth anniversary of Forsyth County’s expulsion of practically all Black residents. The march was met by a massive counter-protest of people yelling “Go home, niggers!” Overwhelmed, the protesters retreated, then returned with a larger number and a significant accompaniment of National Guard to protect them. Hosea Williams, who marched alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. at Selma, said, “I have never seen such hatred.” Oprah Winfrey covered the event in the first year of her show—you can watch the video—but cut short her stay due to the town’s racial animosity.

Patrick Phillips is the author of Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America. Published last September, the book chronicles the racial history of Forsyth County, going back to the Civil War and ending with it being fully cemented as an Atlanta suburb today. Growing up, he’d heard rumors about why there were nearly no Black residents in Forsyth County (in the 1990 Census, fourteen of 44,000 residents were identified as African-American) despite its proximity to the very integrated metropolis of Atlanta. A classmate told him about a girl who had been raped, and in response the town had “run all the niggers clean out of Forsyth County.”

As an adult, researching to write this book, Phillips learns that his classmate hadn’t been far off the mark.

He mixes archival research and interviews to piece together a story that explains how more than 1,000 African-Americans lived in the county in 1911, but a year later were almost entirely gone, and remained gone for the next seventy-five years. We learn about Mae Crow, whose rape in 1912 led to two Black teenage suspects being found guilty by an all-white jury using testimony given under threat of violence and prosecution. State law at the time prohibited public hanging, but the teens were hung in view of 5,000-8,000 observers anyway. The trial and hanging triggered a number of riots, lynchings, and ultimately a systemic, violent campaign to remove the Black population from the county. We also learn how the remaining white population reaped the benefits of the removal. Black homes were ransacked, and vacated Black property suddenly reappeared on the tax rolls a couple of years later, under new white owners but without any record of a sale.

The theme of Forsyth County’s story is one of isolation. The county’s upper-class businessmen are repeatedly at odds with the people enforcing Forsyth’s whites-only policy because it scares away outside investors and a possible railroad branch, but they rarely dare to act to stand up against the bigotry. One week after a lynching in the public square of the town, a newspaper reported that “quiet reigns” in the county. A month later, five Black churches were burned to the ground. And in the language of these businessmen and their political counterparts trying to explain away Forsyth’s racism, you’ll find phrases that echo with conversations still had today. “Outsiders” and “agitators” are blamed, both for the riots and lynchings in 1912 and the counter-protests in 1987, as well as for the marches in 1987 themselves. In the midst of the racially-based expulsion, the sheriff of the county “describes a white population in terror of an impending ‘uprising on the part of the blacks’ . . . when in truth the only real ‘uprising’ was being carried out by white vigilantes and arsonists.” In 1980, when a Black man was shot while visiting Forsyth County with his girlfriend from Atlanta, the local Gainesville Times pointed to the shooter’s conviction by jury as having “exploded the myth” of Forsyth’s bigotry.

Seven years later at the 1987 march, Forsyth residents waved a banner that read “Racial Purity is Forsyth’s Security.” The victim of the shooting marched along with them, saying, “’Seven years ago, I could have been dead for no reason and never known what I was killed for.”

It’s not until the suburban sprawl of Atlanta overtakes the county that it becomes reintegrated. But the legacy remains. No memorials have been erected to commemorate the town’s bloody racial history, but a statue of the Confederate Colonel Hiram Bell still stands next to the county seat’s city hall. Bell was a noted opponent of what he called “this attempted social revolution, to place the African upon an equality with the Caucasian.”

In 2015, Colonel Bell was honored by a Confederate re-enactment unit. The North Fulton Herald covered the event, and called Colonel Bell “One of Forsyth County’s most distinguished and prominent figures in history.”