Burnt Memories: Reading Gabriel García Márquez in Texas

It took every fiber of me not to rattle off a quick ditty about Gabo the night after he passed. I tried, of course, but then where do you stop? Fifteen thousand words? Twenty? In this digital age you’re late even if only by a day, which seemed appropriate actually, because I’m a Texican—A Texas Mexican. And in true Texican fashion, I’m always late to the good things: Warby Parker glasses, Death Cab for Cutie (after they were cool circa 2004), hating LeBron James (only after the Heat beat the Spurs in the finals last year), and Gabo too—who was the only Latino I’d read by seventeen years old, when I decided I was going to be a writer.

To this day, I actually don’t know where I got the idea to be a writer, but I know it was Gabo who showed me it was possible. Before then, I didn’t even know Latino writers existed. Latino writers were left off the curriculum completely in the Texas public schools I attended, and in other places they were banned altogether.

There was, and still is, a certain shame about growing up Latino in Texas, and especially Mexican-American. It’s a kind of shame inflicted by the very stories and mythology of the state, which you learn thoroughly in Texas public schools: Davy Crockett and his crew, who fought at the Alamo against a ramshackle Mexican army who outnumbered them by the thousands; the “heroics” of the Texas Rangers, who always won their gun battles against legions of dim-witted Mexican bandits; and some lady who defied an entire Mexican army by pointing a cannon at them, which actually ended up being some vaguely NRA-positive lesson injected into our textbooks about armed resistance.

Basically, you learn a whole lot magical realism in Texas Public schools, which primes you perfectly for One Hundred Years of Solitude—which came to me like medicine after a very, very long cold.

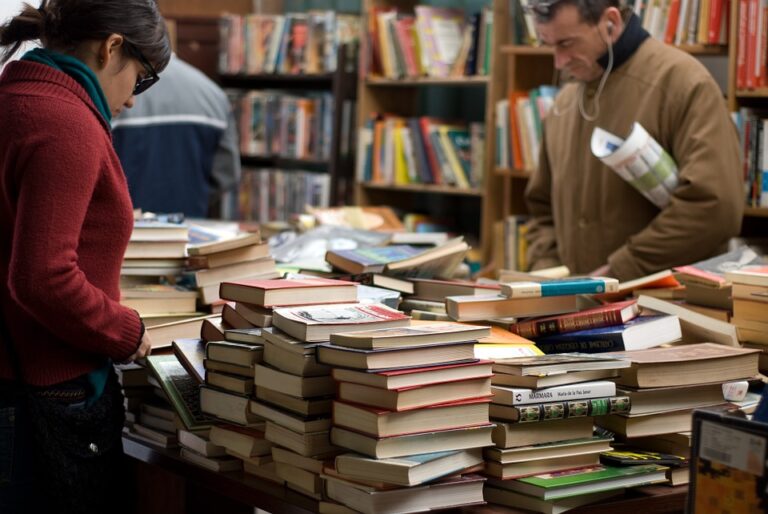

I remember I found the book in the discarded bin at my high school’s library, where I worked for free to get credit of some kind or another. The book itself was pristine along the spine, never cracked, though some schmuck had taken to using the first pages as an ashtray. Little cigarette burns three or four pages deep dotted the pages every third sentence to interrupt the narrative, singe marks that faded from black to brown and then to black again, where the ink took over and ran for a little while till the next cigarette burn ate away the words and disappeared them into a hole, lost forever.

No matter. I took the book home and read it anyway, gaps and all, with no pressure whatsoever to understand the thing or dissect it in any intelligent way. That was probably for the best. The cigarette burns shielded my ego from the largeness of the Buendia plot and the epicness of such a masterfully crafted narrative, which I think would have discouraged me from writing. Something about those cigarette burns made the first pages approachable, silly even. And I became obsessed with the language of it more than anything else—those lost words burned away, ashing somewhere out in the world along with the remnants of tobacco and dust.

The smell of the book, like a cheap motel, and the name emblazoned on the cover, Gabriel García Márquez, made the physical book itself illicit to me. Here was physical proof that Latinos were, indeed, writers—and here it was in my hands, a physical, no-bullshit, hardcopy artifact that couldn’t be denied. Never mind the fact that Gabo was Columbian. His last name was my mother’s maiden name, his first name was my cousin’s, and his language was our own, or at least my mother’s own (my Spanish is notoriously busted, Spanglish more than anything). But here was a book originally written in Spanish and then translated to English. What a concept. What a fresh idea to seventeen-year-old me.

I devoured the book in a night and then immediately sought out other writers like him—Carlos Fuentes, who is largely credited with “discovering” Gabo, and then the rest of the Latin American boom. Julio Cortázar, Juan Rulfo, Mario Vargas Llosa. And then after that, Chicana/o writers, like Sandra Cisneros, Dagoberto Gilb, Jimmy Santiago Baca, Helena Maria Viramontes. And then after that, contemporary Latino writers from everywhere: Junot Díaz, Ernesto Quiñonez, Nelly Rosario, Edmundo Paz Soldán, Rodrigo Hasbún, Diego Fonseca.

But in the beginning, for me anyway, it was Gabo who was there, bringing me in from the darkness, the language from that book whispering through the burns in a language that was so very Texican, full of gaps and ruined pages and little things deleted or left to the imagination. How Texican—to make it up as you go.