Call and Response

Guest post by Greg Schutz

As a reader, I’m fascinated by those moments when literary influence–which usually has a way of creeping up on an author, sneaking into her writing through some backdoor of the subconscious–moves out of the shadows and into the open, when an author acknowledges her influences and shapes her work in conscious reaction to them. Sometimes, when this happens, two stories can be set side-by-side–a call and a response.

Mary Yukari Waters’s wonderful story “Rationing,” from her 2003 collection The Laws of Evening, spans some thirty years in the relationship between Saburo, a quiet boy who grows into an emotionally reserved young man, and his father, a professor of astronomy whose thoughts and feelings are masked from Saburo–and the reader–by an emotional reserve of his own, which appears to be equal parts dignity, formality, shyness, and Saburo’s own projections. Trapped within themselves, the two men repeatedly fail, over the years, to connect. Saburo, a civil engineer, compares their relationship to “the railroad they were drafting at work, its parallel rails never touching, yet exquisitely synchronized, committed in their separateness as they curved through hill and valley.”

This arrangement finally crumbles when Saburo’s terminally ill father enters hospice care–at which point, however, it may be too late for any emotional thaw to have much effect.

Although “Rationing” is remarkable for a number of reasons–including its sweeping timeframe, its understated but precise language, and the way years of suppressed emotions crest like a breaking wave in the final scenes–it’s the outwardly unremarkable beginning of an otherwise unremarkable sentence, buried in the middle of an expository sentence several pages into the story, that has caught my eye: “Dinner table conversations, more often than not, were monologues on the moons of Jupiter . . .”

I can’t offer proof for my suspicions, of course, but I’d be surprised indeed if the above sentence weren’t a case of “Rationing” offering a bit of sidelong acknowledgment to its forebear: Alice Munro’s 1982 short story “The Moons of Jupiter.”

The similarities between the two stories are numerous. Both concern emotionally reticent adult children struggling to connect with ailing and equally reticent fathers. Both stories take the “long view” of their narratives, delving into the personal histories of their characters over many years. And both lead to climactic scenes in which emotions that have long been suppressed, denied, or ignored by parent and child alike must be at last confronted–or else buried forever.

In one story, a father holds forth on the moons of Jupiter at the dinner table. In the other, a daughter distracts herself in a planetarium and then names the moons of Jupiter in a conversation with her father shortly before his open-heart operation.

There are differences, of course. Munro, in her pursuit of the “long view” I mentioned above, is distinctly, well, Munrovian, and “The Moons of Jupiter” is characteristically discursive. Propelled by the voice of its first-person narrator, it weaves its way through time, and the layering of timeframes creates an effect very similar to that of memory–another place where multiple timeframes are stacked one atop the other. (This structural invocation of memory is a feature of many of Munro’s best first-person stories.)

“Rationing,” meanwhile, is more linear. The story starts at its chronological start and ends at its chronological end. It’s told in a relatively cool, detached third-person. But both the structure and the narration suit the story’s purposes–a straightforward structure for its quiet, reserved characters and a form of narration that can largely remain emotionally detached, while occasionally dipping into free-indirect discourse to render moments at which Saburo’s composure cracks.

What interests me about call-and-response story pairs like “The Moons of Jupiter” and “Rationing” is the way that looking at them together allows me to see each one more clearly than I could if I were considering it alone. Their similarities throw their differences into relief–and vice versa. Each story acts as a lens for the other.

A similar connection exists between Andre Dubus’s story “Killings” (Finding a Girl in America, 1980) and Richard Bausch’s “Fatality” (Someone to Watch Over Me, 1999), two stories of fathers driven to the edge. Both are tales of parental grief, protectiveness, and rage; in both, legal recourses prove impotent or insufficient, and each father ultimately finds himself alone in the dark woods with the person who has harmed his child and a loaded gun.

So much, though, for the similarities. It is what happens after all this–after the guns have been fired and each father has returned home–that sets “Killings” and “Fatality” apart. The two stories’ many similarities highlight the marked differences in their denouements.

Really, it makes little difference whether I’m right and Mary Yukari Waters actually meant to give Alice Munro a veiled nod. For the insights it affords, the comparison between the two stories itself is what’s important, however we manage to arrive at it. But there are other calls and responses that have been well-documented by critics: Raymond Carver’s “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” as a response to the stories of Chekhov’s “Little Trilogy” is one example. And according to one of my former instructors, Alice Munro’s “Labor Day Dinner” is a response to “The Dead” by James Joyce.

There are also cases in which the author openly acknowledge the influence and uses it to his advantage: “The Killers” by Ron Hansen is a wonderful riff on the famous Hemingway story of the same title. (We’re approaching the point at which literary influence, shifted from the authorial subconscious to the conscious mind, begins to provide the ingredients for metafiction. See Robert Coover‘s delightfully twisted almost-fairy-tales like “The Magic Poker” or “The Gingerbread House.”)

Readers: have you ever encountered any calls and responses like these?

Writers: have you ever consciously written a story in response to another author’s story? Are there any stories to which you’d like to respond? I think it would make an interesting writing exercise–an attempt to grab hold of that slippery thing called influence, to start with another author’s basic materials and see what new thing you can build.

This is Greg’s ninth post for Get Behind the Plough.

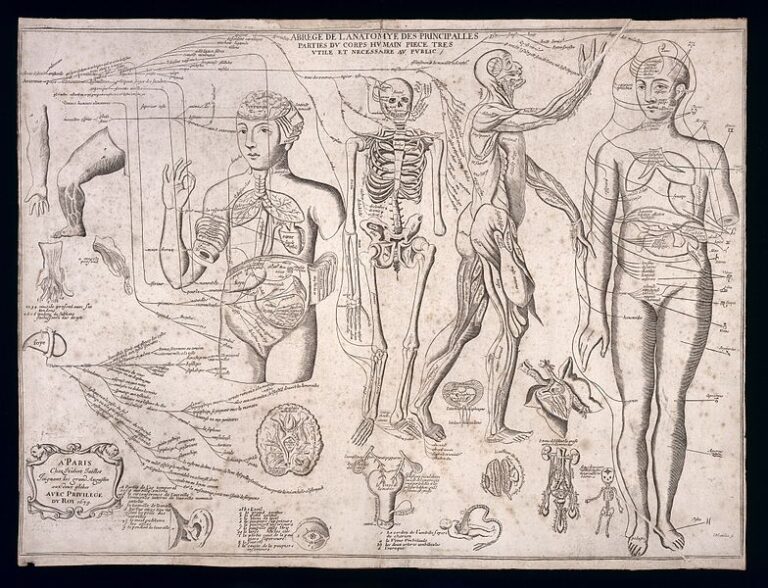

Images: 1, 2, 3, and 4.