How Do We Decide What to Read?

There are too many beloved books and not enough prizes, and somehow they get lost underneath all the news about the really important books that I should be reading.

There are too many beloved books and not enough prizes, and somehow they get lost underneath all the news about the really important books that I should be reading.

Set in 1970s Ireland, Dorothy Nelson’s In Night’s City is an obscure, deceptively slim book. Unofficial predecessor to Eimear McBride’s A Girl is a Half-formed Thing, the novel charts Sara’s attempts to assimilate sexual abuse, suffering, and shame.

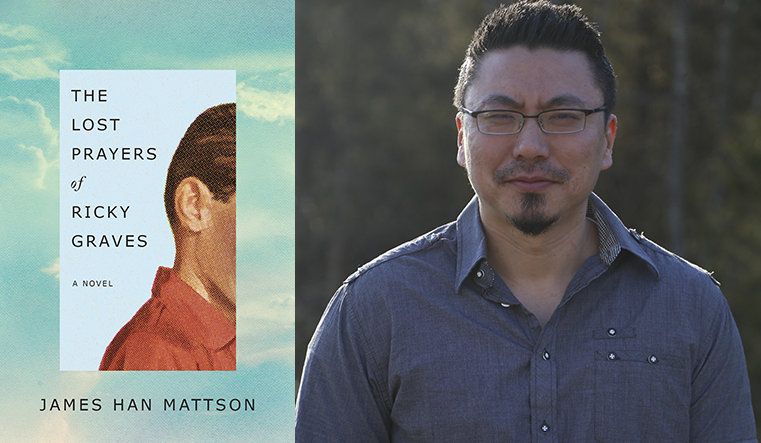

The Lost Prayers of Ricky Graves starts, like many books set in a small town, with a homecoming.

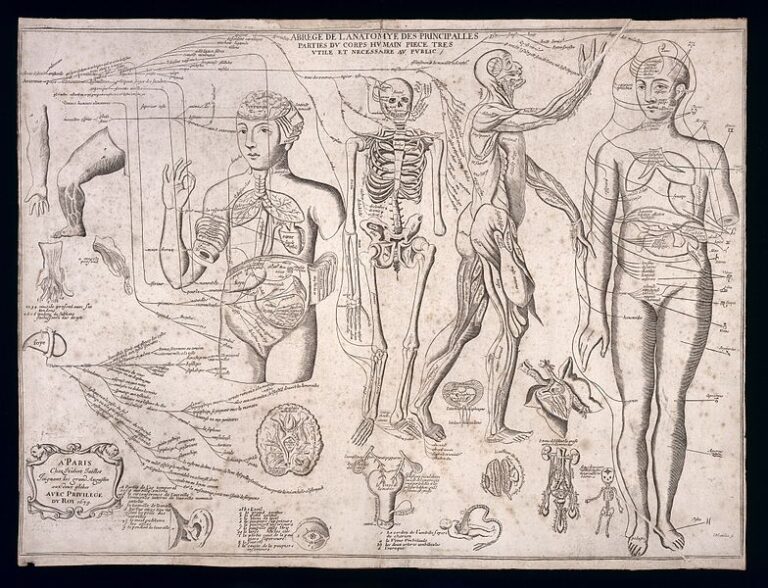

How to control the body is a constant theme in Washuta’s work.

How might the practice of scansion as a tool toward understanding and crafting poetry become more equitable and expansive so as to allow for poets’ and readers’ different fundamental orientations toward language?

Hardy humanizes his heroines’ ambitions, the intensity of their feelings, their fancies and passions. In both Bathsheba Everdene and Tess Durbeyfield, Hardy writes intelligent women who work hard and write their own rulebooks.

The point is to understand that what constitutes “literary” versus “genre” fiction—an age-old topic of study and debate within literary circles—is fundamental, not ancillary, to scientific findings on the effects of reading novels.

The need to figure out why we are who we are is what drew me to Elissa Altman’s memoir Treyf, a bittersweet and touching memoir of the author’s growing up years in 1970s New York City and Queens.

Perhaps in times like these, when the work of making sense of the world around us gets harder, we need poetry that points toward that difficulty—and that makes that work worthwhile.

No products in the cart.