Civil War Christmas Traditions in Little Women

Every Christmas, my mother and I watch a film version of Little Women, based on Louisa May Alcott’s book we read together when I was a child. This book and all it represents of our Christmas traditions has meant a lot to us over the years—as much as decorating a tree or singing carols. It’s a moment of togetherness, and the snowy scenes of glad tidings and cheer put me in a Christmas mind when the California palm trees and sunshine around me feel incongruent.

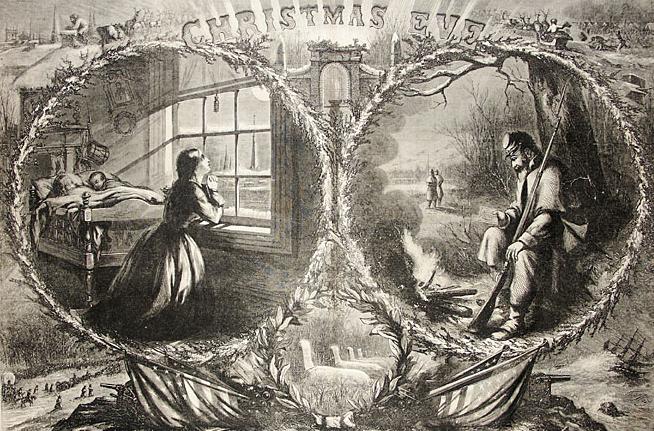

Many of Little Women’s most pivotal scenes are set during Christmas time, although the book spans more than a decade. Its first volume, originally published in 1868, opens and concludes with Christmas scenes, showing how much has changed in each of the four sisters’ lives over the past year. Notably, the novel opens some time in early the 1860s, in the midst of the American Civil War. The girls’ father is away from home, serving as a Chaplain to the North, his safety and absence the backdrop for each of the domestic scenes around which the novel revolves. Christmas didn’t become a federal holiday until 1870, an attempt by President Ulysses S. Grant to unify the North and South five years after their bitter battle ended. Before the war began, in fact, the holiday wasn’t celebrated much in New England, where Little Women takes place. The Puritans and Calvinists who colonized the area stuck to fasting and stricter rituals, and once Massachusetts became a state, schools and businesses didn’t observe the holiday. Elsewhere in the country, Christmas was celebrated according to the customs of the immigrants who settled there. But the Civil War brought a Christmas which relieved the pain of a separated family and restored the peace of a hearth surrounded by loved ones. By the time the war ended, Christmas had become a symbol of family and good cheer.

Christmas also calls the sisters to reflect on their bonds with each other and their parents, and on the kinds of lives they want to lead. Little Women opens with Jo, the tomboy sister Alcott based on herself, lying on the rug, grumbling, “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.” The first volume of the book works to disprove this notion, calling on the girls to reexamine the role of Christmas in each of their own lives. At first, they complain that they won’t have presents, admitting they shouldn’t be upset about this, but each thinking about “the pretty things” she wants, books and sheet music and drawing pencils, each desire so characterizing of its source. But when their mother arrives home with a Christmas letter from their father, the girls sit around and listen to his words. “It was a cheerful, hopeful letter, full of lively descriptions of camp life, marches, and military news; and only at the end did the writer’s heart overflow with fatherly love and longing for the little girls at home,” we learn. “Give them all my dear love and a kiss,” their father writes. “Tell them I think of them by day, pray for them by night, and find my best comfort in their affection at all times.” He promises that when he comes home, he’ll be even prouder and more fond of his “little women.”

“I’ll try and be what he loves to call me, ‘a little woman’ and not be rough and wild,” Jo vows, as chastened as her sisters by her father’s words. The next morning is Christmas, and Marmee asks the girls to sacrifice yet again‚ this time their Christmas breakfast to a poor, starving family. But that night their generosity is matched with a Christmas surprise, pink and white ice cream “and cake and fruit and distracting French bonbons, and, in the middle of the table, four great bouquets of hothouse flowers.” Their wealthy neighbor learned of their Christmas good deed from his servant and sent them “a few trifles in honor of the day.” In their world, good deeds and kindness are rewarded at Christmastime.

The following Christmas sees two more miracles, Beth’s recovery after scarlet fever and the surprise, once again facilitated by their wealthy neighbor, of their father, back from the war. “There never was such a Christmas dinner as they had that day,” Alcott writes. “Just a year ago we were groaning over the dismal Christmas we expected to have. Do you remember?” Jo asks her family. The holiday bookends of the first volume serve to show that as much as has changed, the family’s reunion is the reward each of them deserves for their self-sacrifice during the war.

Later scenes during Christmas, although dampened by the return of Beth’s illness, are symbolic too. But the narrative promise of fulfilled wishes and spoken dreams changes as the sisters mature. They celebrate the holiday apart, but send letters and presents reminiscent of their youth. Still, it’s fascinating to watch the early beginnings of American Christmas, at a time when our country had torn itself in half. It fills me with the March sisters’ belief that Christmas is a time for miracles.

This piece was originally published on December 25, 2018.