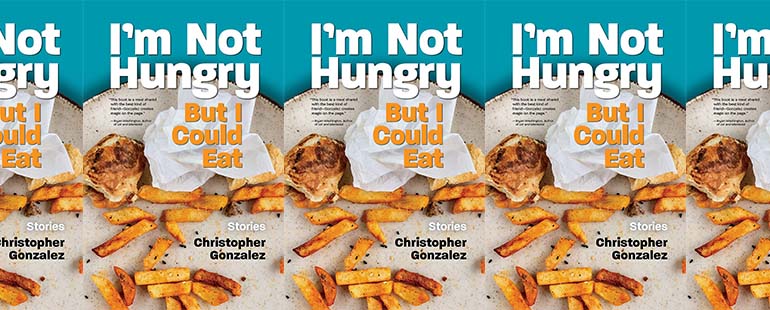

Community and Junk Food in Christopher Gonzalez’s I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat

Christopher Gonzalez’s I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat, out earlier this month, is a collection of short stories in which the narrators and protagonists are all Puerto Rican men who are bisexual or gay. Most of the stories revolve around the characters struggling within their own skin, their own bodies, whether because of their family’s bigotry, their body types, or the isolating and oppressive world that surrounds them. Most of the stories also revolve around characters meeting up to eat (or reminiscing about late-night diner runs alone or with friends) to cope with the negative world around them. The physical act of drinking and eating is always tied to the systemic struggles they experience beneath the surface.

Millennials have often heard how they can’t buy houses, can’t live the American Dream, because of their frequent purchase of avocado toast. In a culture in which you’re supposed to somehow pick yourself up by your own bootstraps, it is the avocado toast that is weighing millennials down. This is the same culture that blames people with dietary and gastrointestinal issues on their choices, rather than on the system that creates food deserts, that makes fast food and “junk” food more available and affordable than fresh products. This is the same culture that doesn’t want to ask itself why these issues affect so many people of color, so many LGBTQIA+ peoples, so many peoples who can’t afford to pay extra for organic fruits or who don’t have the time to cook healthy meals, to go back to the store if the strawberries and arugula they bought had hidden mold, in between their multiple jobs. In Gonzalez’s book, we see characters who go out to eat with each other, eating “junk” food, enjoying this food that may be bad for them, because it is the food they know, it is the poison they enjoy. In a world that poisons them daily, enjoying a good meal with a friend is the best way to chase their struggles away. This is why Gonzalez has one of his narrators say, in the title story of his collection, “For friends, I make time. For best friends, I make room in my stomach.”

Gonzalez’s book opens with the short story “Packed White Spaces,” in which the narrator’s friends are hosting a house party for their new Washer-Dryer unit. The piece starts with the narrator noting the differences between himself and everyone else at the party. It isn’t just being Puerto Rican in a “packed white space” that makes him feel separate—it’s also suffering the bigotry of people who are homophobic, it’s also having less means, being of a different class, living less healthily. Junk food with friends is often the closest thing to healthcare that so many people of color, so many LGBTQIA+ people, receive. All these feelings, both physically present and not, things both out in the open and underneath the surface, make the narrator feel “instant isolation.”

The narrator says, “In this space, I’m wondering if it’s related to Money. Does Money have the power to stave off weight gain from fast-food dinners or a family history of diabetes? Does it cancel out the effect of a 2AM diner run for disco fries and syrup-drenched French toast?” These are the crutches, the pleasures that people of his class, of his sexual orientation, use to feel normal, to enjoy a moment, to connect with the wounds that he needs to attend to in order to heal. Here, the narrator is thinking about late-night diner runs because he is missing their ride-or-die, Alejandra. The narrator never felt alone with Alejandra around. Alejandra’s presence made him feel seen, despite his “inadequacies”, his being less “fit,” his having more “casual clothes.” Alejandra meant that he had someone who would go with him to the diner to laugh at the ridiculous world that for some reason laughs at people of his class, his size, his sexual orientation. But what does one have when, in this lonely world, their ride-or-die passes on? What is there left besides the bad habits, the simple pleasures, the only things you can afford in a world, in a country, that puts a price on everything? What other ways are there to cope than to retrace the steps, relive the memories, and reexplore the tastes shared with those who’ve passed on?

In the story, we see the difference of these precious moments of late-night diner runs when the narrator mentions his relationship with his friend’s boyfriend, Allen, by saying that they’ve “shared a $200 bottle of Macallan the night before graduation, but ask me, have I ever looked him in the eye?” While the price of the bottle is higher, and the quality of the scotch is better, meaning there’d be less of a hangover, less residual or questionable ingredients involved, the connection wasn’t there. The friendship wasn’t there. Allen wasn’t a friend that made the narrator feel seen, that needed cheap disco fries and well whiskey, that learned to enjoy junk food, turning those meals into comfort food after the struggles of being Puerto Rican, of being LGBTQIA+, of being a lower-middle-class millennial living through multiple market crashes. Allen doesn’t desire or enjoy these “cheap” treats, the ones that slowly kill you. This is a world in which sharing fries with a best friend and eating a plate of French toast where not a single part of the plate is not covered in syrup is a memory worth hanging onto—more so than a $200 bottle of scotch filled with silence.

At the washer-dryer party, when wine spills on the narrator, staining his hoodie, he describes it “like a bloodstain, a wound.” He says, “The room goes horror-movie quiet. My instinct is to yell, to tell the guy who bumped into me to watch himself. I fight it. I don’t want to be the angry brown guy in the room.” The hoodie being stained felt almost like a scarlet letter to him, the red stain and unwanted attention upsetting him more than anything else. He didn’t want another reason for people to stare and whisper at him. The stain turns the narrator into even more of a prop, as his hoodie is thrown into the washer and dryer in order to show how new and clean this machine can make things. When the machines stop, the narrator nervously looks for a photo of Alejandra, having forgotten that he had one inside his pocket. The story ends with the lines, “I sprinkle the photo’s wet remains into her palm, let them rain down in fat clumps. We can no longer make out the full picture, but the scraps, I tell her, the scraps are worth keeping.” The memory of Alejandra, of those late nights together, of those beautiful moments, are worth keeping even as just “scraps,” just like the scraps that those of us in lower classes have to get used to.

The title story of the collection, “I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat,” opens: “I’m finishing up a falafel I picked up after work when I get Valeria’s text. She’s going through it and asks if I’m free to catch up at the diner we both like. It’s been a few weeks since we last saw each other and shared a meal, and I know going through it is code for something with work, something with the family.” This story is the perfect place setting for the importance of eating junk food to escape the world. The narrator in this story eats as a simple form of pleasure he can afford, at least monetarily, and it is also the best coping mechanism, connecting activity, he has with his friend, Valeria. Sitting down and doing nothing, while talking about the heavy things that hurt, the heavy things that can’t be physically changed but could end you—it is easier to chase it down with fries, with a simple pleasure, a simple poison, that you can at least eat.

The junk food, the comfort food, is a home to the both of them. We can see it right when they get to the diner, as “Valeria doesn’t need to see the menu. She orders grilled cheese with tomatoes and mushrooms. She skips the fries, which means she’ll pick a few from my plate.” They understand each other, know each other, are here for each other. But we also see, in the very next line, the toxic temptations rear their head, as the narrator changes their order from a chicken club to a buffalo chicken sandwich with extra sauce, despite not being hungry. The narrator tries to be as friendly as possible, tries to consume as much of Valeria’s pain and struggle as he can, but it only ends up being more toxic for him, to the point where they wonder if they’ll “pop” when poked with a fork. But in a world that is toxic, choosing your own poison is so key, so pleasurable.

Being of a generation that has seen multiple market crashes, never-ending wars, and a pandemic, it is hard not to see the world as a place that is toxic in general. Gonzalez’s narrators all being Puerto Rican, LGBTQIA+, lower-middle-class—it is hard not to see the oppressions and forces working against them as being poison, as being isolating. Living in a country that sells the myth of being picked up by your bootstraps, it is hard not to fall into despair. So for the generation of people that apparently can’t buy a home due to our insatiable craving for avocado toast, in I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat we see characters whose best chance at connecting is through a good meal. Characters who need the satisfaction, the instant gratification, to connect with one another, in this world where connections are becoming harder and harder to foster.

So our peoples go out to bars and eat food that is bad for us, food that will mess with our stomachs and hearts and livers, in order to be present for a friend, to make time for a friend. We make room in our stomach so that we have the excuse, the pleasure, the enjoyable hypnosis, to connect with someone, to try to remedy our wounds, to try to share our love. For whether we are hungry for food or not, we are hungry for the connection, for the pleasures we can afford, for the love we can’t afford to love.