Compost Season

It’s that time again. My university’s semester has ended, and while this does not, alas, mean that I’ve logged any hammock time, nor that all my interns for August are placed, nor yet that a certain grisly assessment report is approved by all relevant parties…it does mean opening the composter.

In our semi-rural one-acre lair, compost is a perpetual struggle. If you were raised by wolves biologists, it’s common to bring to adult life both a pathological fear of waste and a conviction that not only should you not build on the flood plain, you shouldn’t let anything go into the simmering anaerobic soup of the landfill that could possibly be recycled, reused, or composted. That means grease and bones are fed to dogs or crows, seal-up bags get washed and reused (if never entirely dry), and plastic, glass, and metal get recycled to the extent allowed by the county’s system (or, sometimes, slightly beyond, as in, “if we sneak in a 5, maybe they’ll just take it anyway!”) And it means compost of anything resembling vegetable love, whether or not you have anywhere appropriate to put it.

For instance, there are coffee grounds, a large handful every morning. There are eggshells, kale stems, cabbage cores, cucumber peels. There are peach stones and lemon peels (very resistant) and strawberry hulls, the end of someone’s salad, the unsavory contents of the sink strainer, and the tea bag whose staple will presumably rust in the fullness of time. Unless you were making soup or stew that week, or had the foresight to be saving things in a freezer container for the ever-popular ScrapStock, there are celery tops, onion peels, and shiitake stems.

The wolves parents have a viable system. It involves several fenced heaps, so that some can rest while others are filling; a rotating composter created by an artist known to posterity only as John the Welder; a thriving earthworm population; and numerous gardens. Their thirty-acre plot has rooms for many heaps, nearer and farther. On our smaller demesne, we began with a square, open-topped, slat-sided composter at the bottom of the semi-vertical yard, a device inherited with the house. It didn’t exactly decompose according to compost best practices, reducing itself to a rich loam, possibly because we kept piling things in and turning it periodically with a pitchfork; but it was fairly inoffensive, at least. When the second-hand composter went the way of all flesh (falling apart slat by slat, offering ever less resistance to possum depredations), the compost situation degenerated into a basic heap, which the crows and raccoons loved (the neighbors, not so much.) It was at this point that we bit the bullet and bought a plastic tumbler, with a seal-tight lid, which we could (in theory) turn over every day to aerate the contents and which would (also in theory) prevent insect and animal incursions.

As is so often the case with academic life, the theory has proven only partially applicable to actual events. For one thing, the tumbler still doesn’t get enough air for quick decomposition (though it’s enough for fruit flies to get in through the vents, giving rise to endless maggots and to speculations about spontaneous generation.) For another, we’re heavy on the wet stuff and light on the dry (hence the bin full of shredded documents that has joined the composter in the front hedge.) For a third, we can’t leave the thing alone long enough to let it really get serious; there’s more compost coming in all the time, because we go through a lot of vegetables.

So, a couple of times a year, we open the composter, consider with a wild surmise the tea-colored ooze reeking of stomach acid and the clots of happily writhing fluke-like larvae, and figure out something to do with it. If it’s winter, we decant it into a wheelbarrow and turn it into the garden (things go faster when the compost is left to its devices underground.) If it’s summer, and the garden’s occupied with kale and garlic, and potatoes, we dig a pit in our stony ground and work in the partially-decayed remains. Eventually, the pit or the garden produces some modicum of loam, if less than anyone hopes. Mixed with the loam are the characters who share a tragic reluctance to relinquish their original forms: eggshells, avocado pits, pine needles.

Still with me? The writing part has finally come around, because while we were grappling with this spring’s hugely heavy, terminally wet, absolutely vile proto-compost, it struck me that this had more than a little in common with writing. Not the absolutely vile part (at least not usually); not the terminally wet (though with poems of unrequited love, one never knows.) But there’s also the waste that you don’t want to waste, the rot that, you hope, will someday suffer an earth change to something rich and familiar. That is, there’s the slush pile.

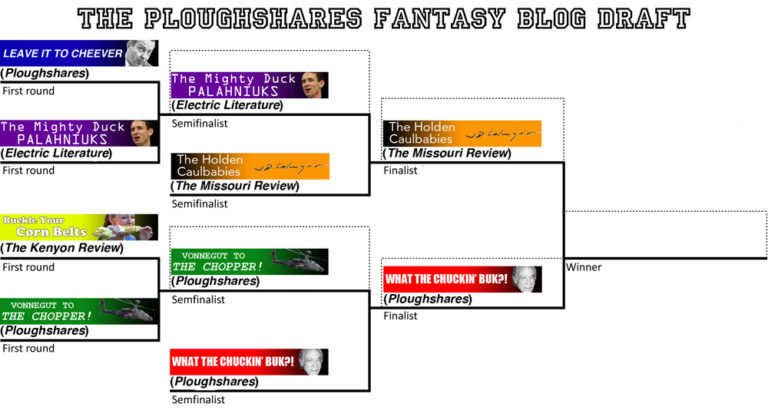

When I teach creative writing (not especially often, what with English education and all, but this fall’s the year!) I like to give the students a handout I call “Some Statistics, or, Why Every Author Needs a Day Job and a Roll of Stamps.” This is partly because I’m so impressed with my own bare-bones ability to calculate percentages and averages that I have to show it off, and partly because I delude myself that it provides some kind of statistical street cred…but mostly because the stats are kind of illuminating. Here are a few:

- Number of magazines which take poetry and are indexed in Poet’s Market: around a thousand, these days. Once as high as 1800.

- Number of poems I’ve written to date (from when I started keeping them at age 14): 1500-1600? (I actually stopped counting these about five years back.)

- Number of those that have at some point seemed good enough to submit: maybe 200, or around 13%. [See that? that’s an honest to God percentage! Poet math!]

- Number of those 200 that I’ve discarded (as my standards have risen) as no longer good enough to submit: probably 70, or about 35% of the total that originally seemed worthwhile.

- Number of publications to which I’ve circulated these two hundred or so, in groups of 3 to 6: 187. But if you count the ones that I’ve wanted to be in badly enough to submit over and over at two-year intervals (Poetry took a decade, or five submissions, and Iowa Review pretty clearly won’t ever happen), it’s at least 300, maybe 400. (I started counting these when I was about 22, or 22 years ago.) If you count the contests and book submissions, it’s well over 500.

- Of the 200 or so poems submitted to the 200 (or 500) venues in the past twenty-two years, number published in journals and magazines: 69 (not counting a few youthful efforts in a few less-than-respectable places or the books, the first of which came out with LSU when I was 39.) So that’s about 34% of the ones that seemed strong enough to submit, or about 4% of the total output, published in magazines and journals, over 22 years.

You can adduce what you will from these numbers (there’s more there than I’m adducing today), but at least one thing is pretty clear: behind the occasional successes, there seeps and steams a very respectable compost pile.

Parts of the pile have finally decomposed enough for transfiguration: some lines from years back have eventually made their way into poems that saw daylight. Sometimes I got lucky, ran across a poem I hadn’t known how to handle a few years ago, and saw immediately what it needed. Those are the days that make you think you’re the Compost Queen, like maybe the poet-gardeners of the world should organize at least a small parade in honor of your recycling self.

Most of the pile, though, hasn’t done that. Peter has already written about this; he concluded that “it’s hard to find something [he] can keep.” And while I’m willing to keep it all (the closets are another story), reuse doesn’t come easily. In amongst the coffee grounds are sonnet lines that seemed good on their own, but whose parent sonnet was never going to cut it (none of my sonnets do), which never will be anything but iambic pentameter. Efforts to work them into free verse, or add a foot and break them into two lines of trimester, are doomed to failure. They’re still sonnet lines, like the dozens of basil stems from each summer’s production of the next winter’s pesto. (If you’re composting basil stems, do yourself a favor: cut them very small, and even then consider tossing them into the woods instead of into the tumbler.) There are poems too sentimental to ever show anyone, but which I love anyway because of what they help me remember. There are all the poems—five hundred? six?—that it took me to figure out I wasn’t going to be writing epics, or odes, or overt dithyrambs.

The thing is, while this ratio isn’t the kind to make the poetic life look good (and while it’s certainly true that not everyone does it this way), I do think it’s okay, like the hassle and labor and stench of the compost. Everyone knows you’re supposed to murder your darlings; everyone harbors the secret suspicion that that really applies to other people’s darlings; but very few people seem to talk about the sheer quantity of what gets composted. Very few people say it’s all right to compost most of what we do. But I think it is. Every part of the basil is precious and necessary to the basil; but the humans eat only the sweetest and most tender parts. Few are the readers who really want to chew on our fibrous stems, our tough roots, or even the flowers that make the bees so happy. Those parts grow the leaves, and they go back to the dirt.

If you’re a working poet, you know this already; but for those who are still figuring out, it’s worth remembering—not only that you can give up on some of what you write, but that probably you can give up on most of what you write fairly early in the process. It’s all right, and in fact necessary, to let go of a lot. Instead of implicitly thinking of these things as stillborn or murdered children, maybe we should think of them as sperm—all but one or two born to die almost immediately—or tadpoles, or horseshoe crab eggs, or squash seeds. The ones that live couldn’t do it without the ones that don’t.

I don’t know what function they serve, the poems that never feel alive enough to put out there on the block. Horseshoe crab eggs sustain immense bird migrations, but with words, the connection is never that clear. But I have faith that they serve some function, that, as in the compost pile, nothing is wasted; probably the horseshoe crabs know little and care less about the red knots or the ruddy turnstones. Maybe what we rebury feeds something. As the noble but unplanned squash vines currently flourishing among my beloved kale attest, loam is unchancy stuff; we don’t know what will come of what we compost, or when things have been left alone long enough to emerge transfigured and reimagined. It happens underground, in the dark.

This is Catherine’s eighth post as a Guest Blogger.