Considering the Wedding Poem

Most people spend their lives thinking about poetry so infrequently that it takes a marriage (or a death) to coerce them into listening for a moment. The after-party anecdote is no novelty: when one attends a wedding, a poem is read—sometimes written specifically for the event, for the people being wed. What makes that poem suited to the occasion for its making, its public reading; what does one expect from the ceremonial poem? For the crowd at a reception dinner, after cocktail hour, does the poem express the intense love of those being married? Is it different from a toast? Does it approximate the reflections and conversations cherished in making this lifetime decision? Does that disagree with the party’s levity? Who does the poem include in its audience besides everyone in that moment? I suspect the answer is anyone who cares, if several hundred years of wedding poetry speaks to the present.

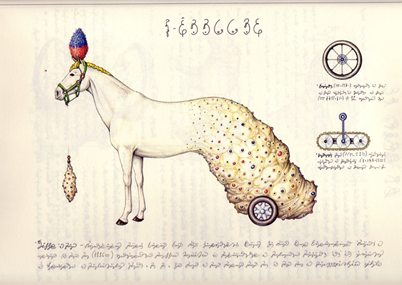

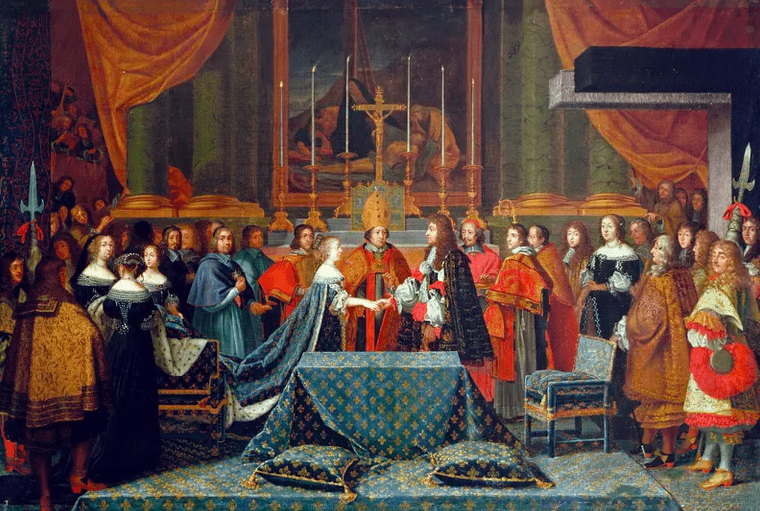

Like most genres of occasional verse, the wedding poem has been around for a while. While the term “epithalamium” has encompassed many variations and parodies of the wedding poem—the “bridal song” dating as early as Theocritus—it traditionally means a folksong performed outside the marital bedroom where the wedding is consummated. In 1594, Edmund Spencer wrote his famous and hugely influential take on the genre, “Epithalamion.” Its twenty-four stanzas begin with a traditional invocation of “ye learned sisters,” the Muses, then move on to record the poet’s summer solstice wedding: “Never had man more joyful day then this, / Whom heaven would heap with bliss.” With a rhetorical flourish, Spencer spends much of his joyful day in a panic, anticipating the consummation of his marriage—and for assurances summoning Hymen, the god who presides over wedding ceremonies. More than a record of the day’s twenty-four hours, the poem deals itself in nervous invocations to stave off all the potential misfortunes of married life: “Let no deluding dreams, nor dreadful sights / Make sudden sad affrights; / Ne let housefyres, nor lightnings helpless harmes.” In the final stanza, Spencer describes his epithalamium as a “Song made in lieu of many ornaments,” the poem a monument of and for his bride.

Like most genres of occasional verse, the tropes one traditionally associates with epithalamiums have manifestly changed (or become altogether less common) since the time in which those poems held explicit social utility. More recently, “In Sickness and in Health,” a poem from the great twentieth-century poet of occasions, W.H. Auden, does not promise the same public celebration of marriage, nor does its wedding occur at a Midsummer gathering. Auden’s 1940 lyric—written shortly after his emigration to the United States, which coincided with his return to the Anglican church—is dedicated to friends Maurice and Gwen Mandelbaum. The lines that follow, one occasionally reminds themselves while reading, are suggested to fictionalized lovers presumed accurate and real outside of this poem, off the page. What did they make of Auden’s poem for their lives, if anything? Similarly invocatory, Auden situates his epithalamium between two representative examples of eroticism and romance: Tristan and Isolde, who “make passion out of passion’s obstacles,” and Don Juan, who Auden calls “their opposite . . . so terrified of death he hears / Each moment recommending it.” This allusive dichotomy mirrors Auden’s own meditation on self-serving love fated to implode—“The decorative manias we obey / Die in grimaces round us every day”—and self-effacing commitment: “That reason may not force us to commit / That sin of the high-minded, sublimation.” Paraphrasing Kierkegaard—who famously ended his own engagement with Regine Olsen—Auden explains that we are always wrong (when facing God), and being wrong, our love asks that we celebrate: “through their tohu-bohu comes a voice / Which utters an absurd command – Rejoice.” The poem pleads that our tohu-bohu relationships to the world, commitments amongst this chaos, might be ruled by virtue rather than temptation.

If through its discursively the poem does not quite memorialize the marriage of Maurice and Gwen Mandelbaum, if the poem does not exact an idiom for the future other than “some glittering generalities,” what is made of the occasion? In Auden’s example, the newlyweds and readers alike are urged to look backward, to the past, for examples of how this commitment might end: “That this round O of faithfulness we swear / May never wither to an empty nought / Nor petrify a square . . .” In these last stanzas, one remembers Auden’s infamously tumultuous relationship with Chester Kallman, whom he met in 1939, and with whom he exchanged wedding rings. When Auden asked for commitment, Kallman was unfaithful. When “In Sickness and In Health” asks that love “remain nocturnal and mysterious,” Auden was permitted—and permitted himself—that mystery. In a letter dated January 18, 1975, written two days after Kallman died, the poet James Merrill remembered their relationship, explaining that he grieves for the older Wystan: “ah but we know how little it takes to be captivated; the point is that it lasted, that Wystan all simply adored C. his whole life long.”

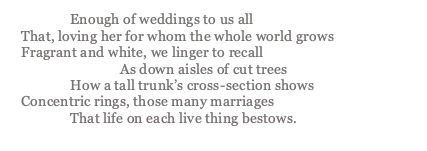

Merrill himself tried his hand at the genre, writing “Upon a Second Marriage” in 1950 for his mother’s wedding with Brigadier General William L. Plummer (she and Charles Merrill divorced in 1939, when the young poet was thirteen). “For H.I.P.”: the poem, like Auden’s lyric, begins with a dedication, though the fictionalized wedding becomes slightly less fictionalized. Regardless, one understands that it doesn’t quite matter if the wedding is real, if the occasion happened with an audience; it matters that we are told to believe that the commitment is real, that the poem was penned for a second marriage. With this occasion announcing itself modified—not a marriage but a second marriage—one almost expects the language to address that modification, an occasion compared to the first, a symbol. Where Auden examined the ring as a symbol that complicates one’s metaphysical relationship—either “this round O of faithfulness” or “the arbitrary circle of a vow”—Merrill found his symbolic circles elsewhere, as the poem’s final stanza recalls:

Merrill’s poem imagines an orchard in autumn, after the fruit has been harvested, as a site of perennial renewal. The seasonal cycle, like Auden’s Kierkegaardian anxiety of Christian love, observes what’s happened in the past to suggest that—maybe—this is what the future could look like. More than a representation of a second marriage, Helen Ingram Merrill’s relationship with her new husband (who is not mentioned in the poem), more than a rational meditation on love, Merrill’s poem is a dutiful assurance for his mother: “Orchards, we linger here because / Women we love stand propped in your green prisons . . .” The occasion of her marriage is a figurative apple tree: one lingers in the orchard to observe its insistence, the fruit it grows.

Thirty years later, Merrill wrote a short poem titled “Epithalamium.” The poem’s two rhyming quatrains announce “Look!” before describing a woman with her hands at the throat of a man in the garment district of Manhattan —until readers learn the first stanza is mistaken, it’s the representation of a man, a clothes dummy who needs his tie knotted. The year before Merrill wrote this short lyric, Louise Glück published her third collection of poems, Descending Figure (1980), in which she included her own rendition of the wedding poem. Like Merrill’s poem before her, Glück’s “Epithalamium” recounts a past image of violence, a vision that changes the more one tries to describe it: “There were others; their bodies / were a preparation. / I have come to see it as that.” Over time, staring at the past tense, ostensibly the same event for the same “others,” the memory has changed. For what, for whom are their bodies prepared? One realizes everything has been cultivated in the ulterior: “And in the hall, the boxed roses: / what they mean // is chaos.” The speaking voice of Glück’s lyric apparently attends the wedding, but the symbols she observes forebode destruction, “the terrible charity of marriage.” (There’s no hope for reconciliation, really.) Like Spencer, the poem is the fragmented record of a wedding day, and that record occurs in the future, after the fact, after the poem can acknowledge that there’s “so much pain in the world—the formless / grief of the body, whose language / is hunger—”. Glück’s poem ends with three lines, the terrifying suggestion of what has happened between then and now: “Here is my hand, he said. / But that was long ago. / Here is my hand that will not harm you.” Long ago, the groom understood his hands to symbolize a smaller vanity—and now, as one reads this poem, his words seem rancid, violent. The commitment expired, this poem is not to be gifted or sung but internalized, reckoned with.

These few examples of twentieth-century epithalamiums—and the poems are so different—suggest something to readers about the degree of our participation in an occasion where, between the several speeches and half-drunken confessions, the congratulations and anticipations, language smacks with figurative static. There, one does not take notes from the epithalamium for instructions on how to arrange a wedding, how to make a marriage successful, how to communicate with a loved one. This language written to the present anticipates its continued listening, sometime in the future. Readers return to the poem then for the experience of reading that poem, before it changes and changes again. In the sixth section in a series of “Eleven Occasional Poems,” Auden includes another “Epithalamium,” but this time, for his niece’s marriage in 1965, he writes with greater levity than before:

For we’re better built to last

than tigers, our skins

don’t leak like the ciliates’,

our ears can detect

quarter-tones, even our most

myopic have good enough

vision for courtship:

It is difficult not to hear, now, a desperate want in this goofiness: one suspects most of this language isn’t honest. The hope is that courtship becomes so straightforward that “we’re better built to last / than tigers”—yet the wedding poems discussed here, at the very least, suggest otherwise.

This piece was originally published on August 10, 2021.