Dead Stories: When to Say When

This week we welcome three new Get Behind the Plough bloggers to Ploughshares. The first is fiction writer Christine Sneed, whose story “The Prettiest Girls” appears in our Winter 2010-11 issue edited by Terrance Hayes. Christine will post on Mondays through April.

Guest post by Christine Sneed

The harsh truth is this: Sometimes it’s time to give up. Yet it can and often does take years for me to reach the decision to stop sending out a poem or prose piece, because giving up is so antithetical to what most of us have been taught about the writing and publishing business. We’re told repeatedly by our best teachers to be survivors, to turn the other cheek when we’re slapped with another rejection letter. We’ve been given examples of now-famous writers who repeatedly submitted their manuscripts to uninterested editors, and in some extreme cases, died before their genius was celebrated in dorm rooms and book clubs everywhere. (I’m thinking of John Kennedy O’Toole and of Nabokov’s Lolita in particular, though fortunately, in the second instance, the author lived to see his masterpiece praised and canonized).

I have submitted some of my stories dozens of times to various self-respecting journals and in a few cases, I’ll probably continue to send them out until my mugshot joins the line-up on the US Post Office’s Most Wanted wall (my crime being jaw-dropping vanity). One of the three previously unpublished stories in my first collection, Portraits of a Few of the People I’ve Made Cry, was rejected more than fifty times. I refused, however, to believe that it had few merits and defiantly included it in the manuscript that won AWP’s 2009 Grace Paley Prize in short fiction. A few of my early readers mentioned how much they liked this story without me needling them for praise, and each time, I felt a moment of relieved vindication.

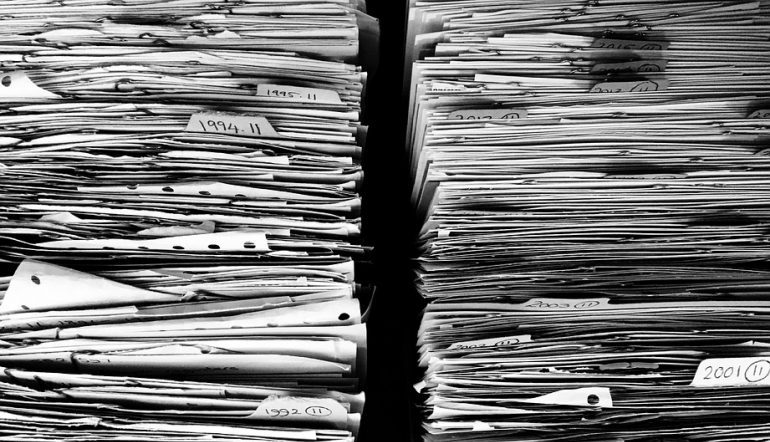

As most everyone who has been sending out work for a few years or more knows, not all of our stories and poems will find sympathetic readers and editors. Not by a long shot. We keep a file of abandoned hopes, one that we glance at on occasion with mixed feelings – wasn’t that story about the guy who dangled himself naked out of a helicopter to impress his estranged wife and daughter a brilliant exploration of middle-aged loneliness and disaffection? Or, how could the editors at The New Yorker have failed to see how original and revelatory my poem about cotton candy and flamingos is?

Maybe we haven’t completely given up hope because we can’t make the final excision–discarding the hard copies or deleting these files from every jump drive they befoul. If the story or poem exists at all in some tangible form, perhaps it deserves to exist?

Yet, if we’re no longer stuffing envelopes and pasting stamps on their faces, I’d say that we’ve stopped showing definitive faith in these works’ goodness. If we aren’t uploading our hangdog files to a submission manager, ostensibly we have given up on sharing with the rest of the world these once-shining examples of our wit and intelligence.

In the last several years, more times than is probably healthy, I have sent out a story only once or twice. I felt the chilling conviction that it should not be sent out at all, but because I had spent two months writing and revising it and only it, the damn story was going out! With the 50-submission survivor mentioned above, I didn’t stop sending it out because enough encouraging rejections had arrived for me to believe that someone would eventually publish it. I had also had the experience of guest-editing fiction for a journal that harvests an enormous number of submissions each year, many, many thousands, and most of the submissions I was assigned were so unready for an editor’s eye that I felt this weird mix of awe and disgust as I read through the pile. I kept thinking, If this is what I’m competing with, why does it take me twenty or thirty attempts to publish a story? I’ve been in Best American Short Stories for goodness sake! Salman Rushdie and Heidi Pitlor declared my story better than thousands of others that had been published in the same year!

The pill I kept swallowing the year after this remarkable acceptance was bitter and frighteningly large: It took me close to a year to receive another story acceptance, even with the BASS 2008 line on my cover letter. I had also already published close to twenty-five stories by the time the BASS call arrived on a day in late February of 2008. It seemed safe to believe that I knew how to write an interesting and publishable short story. But during those many months, I learned and relearned the lessons of humility I had begun my acquaintance with when I started sending out poems and stories in the mid-90s.

In fact, I had almost given up on the story that was selected for BASS 2008. It took me over four years to publish it, and at one point, it sat on my desk for a year and a half and did not go anywhere. I’m not sure why I finally sent it to the New England Review. Desperation? Hubris? A desire to play a practical joke on two editors I respected? Before NER took it, I really was thinking of putting “Quality of Life” away for good. If Stephen Donadio and Carolyn Kuebler hadn’t accepted it, it would have joined the circular file. I’d have lost interest in it, and this, more than anything else, is what happens with the stories that I stop submitting. I get sick of looking at them. I feel ashamed of the black marks and rejection dates that march like fat ants across my submissions log. Maybe the subject matter now seems puerile or else there have lately been too many stories published about stand-up comedians with eye patches or marathon-running pastry chefs who want to move from Newark to Rome. The subject has been covered well enough, and my story looks like a sad imitation.

I don’t believe that most of my dead stories are without merit though. Some of them might still be publishable. But after a certain point, it becomes hard not to think that I’m felling trees unnecessarily by making more copies of “Elegy for a Living Husband” or “Not the Worst That Could Happen.” The US Postal Service might be desperate for my business, but I can’t afford to keep investing in my vain hopes.

The uncertainty of the writing life is discussed again and again in blogs like this one, but it’s a subject with so many variants, so much possibility. When I retire a story, it might only be because I prefer to put my resources into submitting newer material. The old, unpublished story is like the chambray shirt I once loved but eventually gave to the Goodwill. I grew sick of seeing it in the closet, remembering its better days, the thrill I felt to look upon it when it was in less-threadbare form.

The unpublished stories, however, did serve their purpose. For one, they eventually brought me to other stories. And for a while they managed to reflect my best self.

This is Christine’s first post for Get Behind the Plough.