The Lost Letters of Jack Kerouac

“I really miss you. I think you are the only man I know today whose conversation and presence I prize, at last. But don’t talk so much, let me get a word edgewise.” Kerouac wrote these lines in a letter to his friend, Breton author Youenn Gwernig, a little over two years before his untimely death at the age of forty-seven. Kerouac and Gwernig corresponded frequently during the last three years of Kerouac’s life. They exchanged bits of poetry and brazen accounts of their sexual exploits. They schemed about a trip they would make together to Brittany, the western region of France. The two authors were even planning to write a novel together, though this project unfortunately never materialized. If their brief yet ostensibly meaningful friendship has been ignored by Anglophone scholarship, the opposite is true in the Breton community. Touted and celebrated by Breton authors and scholars alike, the Kerouac-Gwernig correspondence is often read as an opportunity to recuperate Kerouac as a Breton author. Kerouac, after all, is a Breton name. A close reader, however, will notice that Gwernig and Kerouac bonded not over Brittany as much as their shared experience of cultural alienation, living and writing between languages and multiple identities.

Recent attention paid to the Kerouac-Gwernig correspondence, at least in France, is due to the fact that the letters have only recently been made public. After Gwernig died in 2006, the letters were passed to his eldest daughter, Annaïg Baillard-Gwernig, a Breton-Franco-American author who was born in New York but now lives in Brittany. She translated the letters into French from the original English. The published form of these letters, however, is rather unique. Rather than in an edited volume, they appear in a book of photography. Breton artist René Tanguy photographed the letters one by one, allowing each letter to take up the entirety of a large-format page. Tanguy intersperses the photographed letters with images of landscapes, mostly in black and white, in Brittany and the United States. The collection, entitled Sad Paradise: Sur la route de Jack Kerouac, presents these letters as works of art, and invites the reader to consider their content in relation to the open, isolated spaces that the photographs portray. Juxtaposing the evidence of an epistolary friendship alongside abandoned landscapes, Sad Paradise echoes the tone which the letters convey: a shared experience of being alone in another’s distanced company.

As authors, Kerouac and Gwernig share an interest in conveying linguistic otherness through their literary work. Kerouac, whose full name was in fact Jean-Louis Lebris de Kérouac, grew up in a linguistically and culturally marginalized community of Franco-Americans who immigrated from Québec to Lowell, Massachusetts in search of work and a better life. Many Québécois were doing the same around that time despite the fact that the “Francos,” as they were called, were seen as alien “others” in the heart of Anglophone New England. Many of Kerouac’s early manuscripts, including several early versions of On the Road, were novels written in French. In his 1951 manuscript novel, La Nuit est ma femme, the narrator states: “J’ai jamais eu une langue a moi-même (I’ve never had a language of my own).” Scholar Hassan Melehy argues in Kerouac: Language, Poetics, & Territory that Kerouac’s Franco-American identity informs the whole of his work. Melehy conducted his research utilizing an archive only recently made available to the public: the Kerouac Papers of the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library. Re-discovering Kerouac as a Franco-American author has led to a re-reading of his use of English as a manifestation of Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of “minor literature.” This concept refers to a linguistic or cultural minority’s use of a dominant language in a process of “othering” or displacing the majority language. Kerouac’s use of English, Melehy argues, is profoundly informed by his deterritorialized identity and linguistic otherness.

A careful reading of Gwernig’s letters to Kerouac brings to light just how much Kerouac’s use of English inspired Gwernig’s use of French. Born in Scaër, Brittany in 1925, Gwernig’s native language was Breton. Like many of his generation, Gwernig learned French in school at a time when Breton was still widely spoken in the department of the Finistère (known as la Bretagne bretonnante), though the language was already beginning to erode. In a rapidly modernizing and urbanizing France, the rural, traditional language of Breton became a symbol of poverty and the past. Later in his life, Gwernig would become active as a musician and performing artist in the 1970s movement of cultural and linguistic revival in Brittany known as Emsav, which loosely translates to “uprising” or “revolt.” In 1957, however, Gwernig, along with many other Bretons, left Brittany for Manhattan to find work in the land of opportunity. Gwernig lived in New York for thirteen years, and even began to raise his three daughters in the city. Eventually, the family returned to settle in Brittany, and Gwernig followed. He was already splitting his time between Brittany and New York when he reached out to Kerouac on a lark. Gwernig was drawn to Kerouac’s name on the cover of a recently published novella, Satori in Paris (1966), which recounts the narrator’s failed attempt to locate his ancestral origins in Brittany. Mailing his first letter to Kerouac’s editor in the spring of 1966, Gwernig addressed Kerouac for the first time with the greeting: “My Dear Sir and Countryman.”

Gwernig and Kerouac corresponded in English mostly, sometimes breaking into French. In his letters, Gwernig taught Kerouac some Breton words that Kerouac played around with like a jazz artist improvising variations from a single note. Writing between three languages, Gwernig expresses an ambivalent sense of identity, at once belonging and not-belonging to all three languages at once. In one letter, from 1967, Gwernig transcribes one of his poems entitled “Libération,” a rare poem that Gwernig wrote in French rather than in Breton. In the same letter, Gwernig grapples with his relationship to France and the French language:

Mind you, I am not throwing the French overboard, I couldnt anyway and dont want to, they’re great, they’re unique, but they’re not the only ones, and I am not one of them. Me American anyway, ah, ah, Breton American.

A Breton-American author reluctant to send the French to the guillotine, Gwernig expresses ambivalent belonging in these letters to Kerouac like nowhere else in his writing. Corresponding with the famous Beat author seems to have liberated Gwernig’s own authorial voice. During these years of their correspondence, Gwernig began drafts of his own novel, which he wrote in French and published with the French press Grasset in 1982, entitled La Grande Tribu (The Great Tribe). This novel is a largely autobiographical account of the thirteen years that Gwernig spent living in New York City. In it, the Breton narrator encounters a whole host of distinctive characters—mostly from Ireland, Germany, France, and Canada—who find themselves in the cultural melting pot which was Manhattan in the 1970s. Throughout the novel, the protagonist, Ange Rosso, an Italian-Breton immigrant to New York—bringing to mind Kerouac’s Italian-American hero of On the Road, Sal Paradise—recounts his struggle to write a novel of his own, which he refers to as “le saga de mon peuple / the saga of my people.” This novel within the novel is never finished. The narrator is continually distracted when he sits down to write, either by the raucous group of immigrants who continually come knocking on his door, or the by the painful memories of all that he had lost—his Irish lover Mildred Moynihan who abandons him and his native homeland, Brittany.

By the end of the novel, Ange Rosso decides to return to Brittany, on a boat with the rather heavy-handed name France, though the “return” to the homeland also remains unfinished. The novel ends with the narrator standing on the deck of France, straining to see the Irish coastline which is lost behind a thick fog. He knows it must be there, but he just cannot see it. He writes one last letter to Mildred, in broken Irish, “Ta gra agam tu go brach / I will love you forever,” and mumbles to himself, “C’était tellement con tout ça ! / It was all such a damn shame!” while he throws the message in an empty bottle overboard. The novel’s conclusion denies the reader the satisfaction of reunification with the lover and homeland. This incompletion, however, is precisely the endpoint that the novel has been working towards. Like Kerouac’s ending of On the Road which mourns the loss of a friend and a father (“I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty.”), Gwernig’s ending forces us to accept that some journeys are not meant to have destinations.

Kerouac and Gwernig had a special relationship. Their bond, however, was not really about Brittany. Instead, these authors connected over their shared poetics of exile. Their identities, like their novels, were in perpetual motion. Both authors affirm their “minority” identities while, at the same time, questioning the possibility of fully belonging anywhere. This is something that minor literatures, in Deleuze and Guattari’s understanding of the term, can teach us. “Only the minor is great and revolutionary,” they write, “to hate all literature of masters.” Greatness, they remind us, is not about where you’re from but where you’re going next.

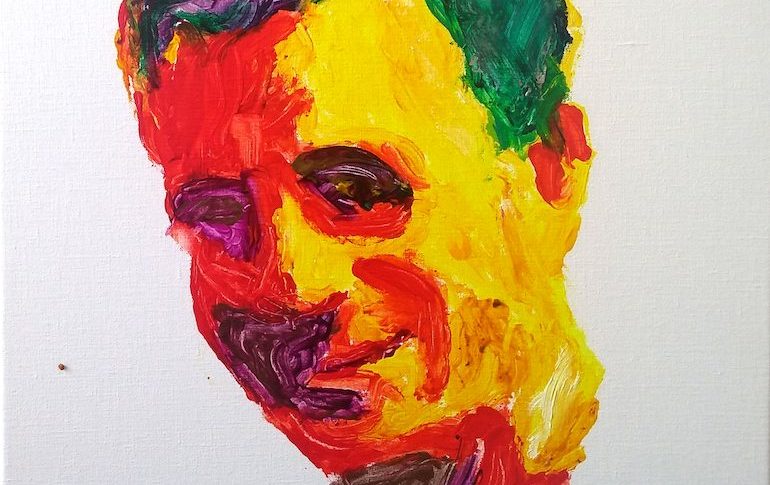

Image by Ante Wessels