Death in Literature: Predicted, Quantum, and All-Too-Human

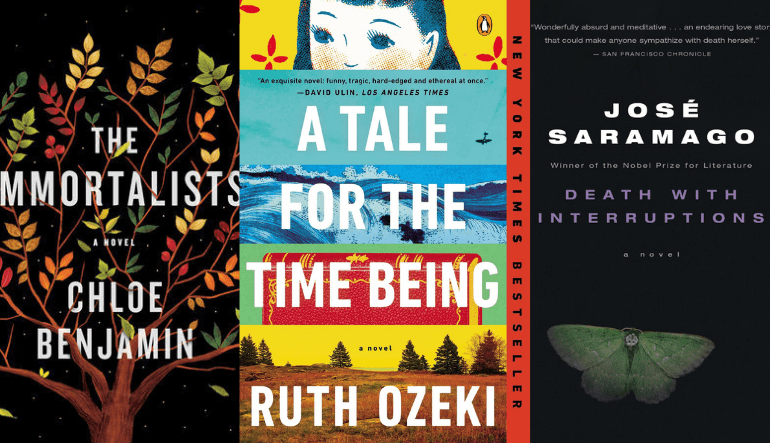

Chloe Benjamin’s The Immortalists begins with a gamble: that a strange traveling woman, rumored to be practicing divination, can accurately tell you when you’ll die. The four barely adolescent children of the Gold family take that gamble, with lifelong consequences. Whether the children accept it or attempt to fight it at all costs, the predictions inform their lives, rearranging its very fabric. Simon, the youngest, destined to die young, acknowledges this on the eve of his death: if not for the psychic’s warning, he would perhaps never have had the courage to run away to San Francisco with his sister and center in his life the truth of his homosexuality—he would not have known love and sex, would not have had opportunities to go beyond himself and search for his inner purpose. Instead, he would most likely have stayed to support his mother and taken up his father’s tailor shop: a dead end. The knowledge gleaned from the woman, then, is a self-fulfilling prophecy, the horizon of all decisions to be made. But the life to be lived can become both a space of liberation, where one is free to live to the fullest, as well as an obstacle depriving one of agency.

Simon dies of AIDS in the early eighties, when the terror of the disease has just begun to sweep through the country. The novel depicts what it is like to be marginalized by oppressive social norms, hunted down by the authorities, and stalked by a form of death that was all the more terrifying because of the complete lack of information about it—what created it, how exactly it was transmitted, how it could be contained. This death felt like an invisible predator.

At the heart of The Immortalists’ narrative project is the voicing of all the anxieties we experience and the minute readjustments we make in the face of death’s radical uncertainty, both for ourselves and in relation to others. That death should be an obsession in literature comes as no surprise—and here I’m thinking less about the incidence of death (plenty of people die on the page, as in real life) and more about the thing itself: at its heart, literature is systematically tussling with the idea of an ending, a life coming to a close. Death’s often opposed to love—there’s the perennial Eros vs. Thanatos binary—though philosophers and psychoanalysts place desire at the heart of both of them. It’s the Unanswerable Question (or one of them, at any rate) and as such it remains uncharted territory for the human imagination, even when faith provides accounts of what will happen beyond the End. Literature, as a territory of creative speculation, then appears especially attuned to tracking our ever-evolving relationship to death and its consequences on how we lead our lives, how we relate to others, and how we cultivate any sort of moral compass.

Thus, writing about death means venturing into experimental waters, both in terms of content and form. Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being is haunted by death, and more precisely suicide—its narrative structure functions on multiple chronological levels and hinges on the conciliation of quantum theory and Zen Buddhism. Texts appear and vanish, circulate in multiple languages, and are sometimes translated with great difficulty; meanings can and will be lost. The protagonist is Nao, a teenager born in the US to Japanese parents, who has trouble adjusting to Japanese society when her parents move the family back. She is bullied constantly, and, in one particularly cruel incident, her classmates shun her, hold a mock funeral for her, and stop interacting with her completely while her teacher plays along. She decides to commit suicide. In the meantime, she tries to write down the story of her paternal great-grandmother, a Buddhist nun, feminist, and bisexual former anarchist, whose son died as a kamikaze in World War II. Her father, a shut-in who withdraws ever more from the world, also attempts suicide. Nao’s journal is uncovered on a beach in British Columbia by Ruth, an avatar of the author—the journal is most likely part of the debris borne by the oceanic current in the wake of the 2011 tsunami. Nao’s fate remains unknown, and to solve that mystery, Ruth delves into the myriad possibilities offered by a quantum understanding of the world.

The resulting narrative is palimpsest-like in its layering; it means to reconcile us with a world that’s ceaselessly in flux. In this context, the very concept of an ending or a beginning make less sense, or at least must be revised: what is effectively ending with Death? José Saramago’s Death with Interruptions (or Death at Intervals in its British edition) discusses death as a social and political phenomenon while creating an anthropomorphized version of the concept. In a landlocked, unnamed country, people have suddenly stopped dying on January 1st. But this newly-found immortality, in which people revel at first, comes with its own set of issues. The Catholic Church is in disarray over what presents a solid blow to their core dogma; the health system is about to collapse under these new demographic challenges. Society is revealed to be structured by death, just like it is structured by its absence. In parallel, a character named “death” emerges, who evolves in the way she relates to the people she is supposed to kill. The novel, told in a long stream-of-consciousness, eschews traditional grammar and punctuation—a hallmark of Saramago’s style but also a materialization of the ways death permeates our very thinking and subconsciously structures our consciousness.

In tarot, the Death card is the card of transformation, both absolute, irremediable, continuous, and recurring—and this is what transpires in the literature tackling head-on what Death means for the very definition of human. It highlights the mutations, the shifts, both seismic and minute, that punctuate our existence as we grapple with the numerous before-and-after moments that deeply transform us. At its core, literature is about death—about what it means to change in a changing world. In Ozeki’s novel, Oliver, Ruth’s husband, asks, “Is death even possible in a universe of many worlds?” Literature is this universe, ceaselessly interrogating probabilities, ceaselessly circling around death.