Dismantling Binary: Three Reviews of Genderqueer & Trans Writers’ Chapbooks

This month, I read work from both genderqueer and transgender writers. Inspired by recent tweets, blog posts, and press releases supporting works by these writers, it seemed a good opportunity to spotlight these three chapbooks.

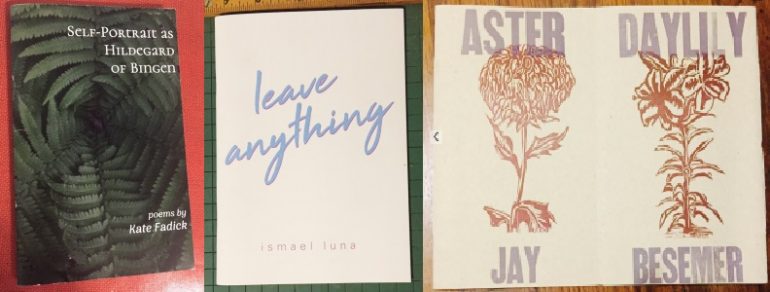

Self-Portrait as Hildegard of Bingen by Kate Fadick (Glass Poetry Press*, March 2017)

Kate Fadick began writing their recent chapbook from Glass Poetry Press, Self-Portrait as Hildegard of Bingen, as a 30/30 challenge. The speaker of the poems forges a connection to the German Benedictine abbess known for her prolific and diverse output of writings, from morality plays to botanical and medical texts to visionary theology.

The opening poem, “Antigone’s Birds,” leaves out Sophocles’ heroine from all but the title, focusing on the world that surrounds her prior to execution. Lines like “one weedy species / wails a broken note or two” (lines 3-4) set the tone for the chapbook: an attention to the everyday and the beauty in the ephemeral and the damaged. Frogs and birds that accompany Antigone in this first poem reappear when Hildegard is introduced in a poem called “Where Light Bursts,” illustrating some of the many motifs that run through the interwoven poems in this chapbook. Additional motifs are certain colors, peonies, berries, and dreams—all that which exists both in Hildegard’s past and in the speaker’s present. The next poem, “In my dream of Hildegard,” showcases some recurring themes: seeing elements of one’s self in a historical other and the realization of a meaningful interiority’s possible effect over the exterior world.

Fadick weaves reference to Hildegard as a visionary throughout their chapbook, such as in “When Hildegard cannot sleep”: “she stays up / all night hidden in the branches / only she can see” (lines 1-3). Hildegard also, in the following poem, “sketches visions on wax / as she sits // on the slash between either / or” (lines 7-8). The title poem opens with a series of negatives, “No voice burning / from heaven / no doors opened” (lines 1-3). The usual clichés in religious ecstasy are not what graces Hilegard nor speaker, instead “only light” (line 5), a revelation of the inevitable death of the universe, as “stars make / their way through / to witness devastation” (lines 10-12).

*Until the 2018 midterm elections, for every Glass Poetry Press chapbook purchased (full price or presale price), they will donate one dollar to the ACLU.

leave anything by ismael luna (Big Lucks, December 2016)

Selected by Ginger Ko, leave anything by ismael luna won the 2015 Big Lucks Best Prize. Ko says, “the lines of this book are skeletal because they are unoccupied—they were written in the future looking back at the fuckery of our present. luna’s missives predict us.” luna’s poems begin and end like waves, in such a way that a reader might not recognize one has ended and the next begun. The book paces itself like a tide, leaving room for a reader to breathe both in and out, eyes moving over carefully shaped white space towards the next compelling lines.

The chapbook builds its politics into poetry, weaving Spanish words in with English. Early on, the speaker folds a newspaper article on a shooting “like / I was taught to fold / homework” (3). Later, while in conversation about a migrant camp set on fire, an interrupting conversant seems most concerned with the language someone spoke, the details of the tragedy far less important. luna touches here and throughout on the spectacle of white grief, as in earlier when the speaker indicates, “say grief enough times / that it loses / meaning” (9); and later, “we are more / than mantles of / trauma // more than / its ripples” (26). The chapbook decenters as it moves, leading readers towards a more honest idea of empathy with any identity it might consider other, stemming from an idea that perhaps any whole empathy many might claim to feel with this speaker would be always already false.

Aster to Daylily by Jay Besemer (Damask Press, April 2014)

Damask Press’s Aster to Daylily by writer and visual artist Jay Besemer features his woodcuts on the front and inside back covers and his prose poetry in a uniquely formatted chapbook that looks like two in one. Besemer’s poems are also distinctive in form, particularly in how they invent their own rules for punctuation through innovative use of the colon. There are many ways to read the chapbook—the Aster side first and Daylily side second might seem logical, but the page numbers take readers from one side to the next until the last poem spreads across from Aster to Daylily in its three parts.

The poetry here concerns itself with binaries, from broad as “is/not,” the title of one of the early poems, abstract as life and death, personified as “the dust world & the blood world” (19), onto the more concrete land and ocean. These binaries are not always indicated as truly oppositional, and the lines that they draw towards and away from each other are not always straight or solid. For instance, a poem that defines its title over and over, “the violence,” ends “the violence of having something to say : the violence of saying it : the violence of saying nothing” (23), drawing attention to the difference in choosing to say or not say something but also the similarity between them—the violence of both. The opposites it creates are constructed and then dismantled. This is also the case in “respectable,” when the speaker advises tying your hands into paper lunch bags so that “you have converted potential abnormality into the most respectable inaction” (21). Here, the other side of abnormality isn’t its most common antonym, normality, but instead inaction.

The false binary between humanity and nature recurs as a theme well. In Aster to Daylily, the ocean can be worn as a coat, hair weaves itself around nails (9) and pistils (12), a machine is “ivy-smothered” (29) and perhaps human all along, and “prairie grass” is “spiked with steel posts : snagging tattered plastic bags” (28). In “meaning,” the penultimate poem, two things are paired together, often an element of nature alongside a manmade object, creating relationships between the two, building new meaning, acculturating new ways to perceive and disarm the world.