Donald Hall, Sharon Olds, and Dani Shapiro on Marriage

I stumbled across Donald Hall’s “The Third Thing,” an essay on his marriage to fellow poet Jane Kenyon, not long before my wedding. Hall’s measured tone and rich details came in sharp contrast to all of the bridal materials I was bombarded with—The Knot checklists that filled my inbox, the glossy magazines with sumptuous weddings I could never afford and didn’t want anyway, and all the options for things like bridesmaid gifts and chairs. Yes, I was grateful to be getting married, but in the swirl of wedding glamour, marriage itself was so easily lost. Work by Donald Hall, Sharon Olds, and Dani Shapiro brought marriage back to life for me.

“What we did: love,” Hall writes.

We did not spend our days gazing into each other’s eyes…Most of the time our gazes met and entwined as they looked at a third thing. Third things are essential to marriages, objects or practices or habits or arts or institutions or games or human beings that provide a site of joint rapture or contentment. Each member of a couple is separate; the two come together in double attention.

My husband and I chose this quote to be read during our ceremony, a talisman for what would come and what we already shared—our dog, books, a love of art museums. For Hall and Kenyon, it was their beloved pets, church, and a favorite pond. Aside from offering a way for a couple to unite outside of the bonds of marriage, third things hold them close through the trials of it, which Shapiro dwells on in her memoir Hourglass: Time, Memory, Marriage. Like Hall—and, for that matter, like myself—Shapiro married another writer (and filmmaker), whom she calls M. Despite all the third things Shapiro and M. share, their son among them, hardships befall their relationship. “I’ll take care of it,” Shapiro’s husband says. But Shapiro must doubt his assertion no matter how much she wants to cling to its credibility. “A familiar refrain,” she continues, “one I have always loved and long to believe. This longing—my longing—is part of our marriage. We have been together for nearly two decades. The woodpecker, the mangy creatures, the hive of words. The creaky house, the velocity of time, the accretion of sorrow. The things that can and cannot be fixed. I’ll take care of it.” Shapiro and her husband push up against the limits of themselves, financial straits they struggle to overcome, major health crises, personal and career failures. The assertion I’ll take care of it falters; the third things fail to ameliorate, to eclipse hardships.

Shapiro’s marriage to M. was her third, although they both had the intuition This is the one when they first laid eyes on each another. Still, her past collides with her present when she and M. accidentally bump into her first husband at a museum. “They shake hands,” she says, “and all my past selves stretch between them like a fragile chain of paper dolls.” That fragile chain of paper dolls is reminiscent of Olds’ description of her parents’ devastating marriage. In her poem “I Go Back to May 1937,” a time shortly before her parents got married, Olds wants to say to her parents:

don’t do it—she’s the wrong woman,

he’s the wrong man, you are going to do things

you cannot imagine you would ever do,

you are going to do bad things to children,

you are going to suffer in ways you have not heard of,

you are going to want to die.

But preventing her parents’ marriage, awful though it was, is to cancel her own life. Her will to live trumps her trauma. “I / take them up like the male and female / paper dolls and bang them together /at the hips, like chips of flint, as if to / strike sparks from them, I say / Do what you are going to do, and I will tell about it.” Like Shapiro, Olds makes meaning of the ugly, fraught parts of a marriage, a theme she returns to when marital discord strikes her own.

Olds’ early poems about her marriage are achingly intimate, and knowing its fate has always felt dreadfully sad to me. The marriage she describes is one of intense intimacy, in part because of the children, a third thing, that bind the couple together; the truthiness in it beckons. In “The Wedding Vow,” she explains, “In truth, we had married / that first night, in bed, we had been / married by our bodies, but now we stood / in history—what our bodies had said, / mouth to mouth, we now said publicly, / gather together, death.” In addition to sex—or, more often, making love—death is also a thread in Olds’ poems; in “The Promise,” she and her husband are “renewing [their] promise / to kill each other” should they become trapped in a body that has failed them. “I tell you you do not / know me if you think I will not / kill you,” Olds tells her husband. “[Y]ou know me from the bright, blood- / flecked delivery room, if a lion / had you in its jaws I would attack it, if the ropes / binding your soul are your own wrists, I will cut them.” This line is a testament to the kind of connectivity married couples can have.

How can a marriage like this fail? Olds’ husband had an affair and ended their marriage, which she writes about in the Pulitzer Prize-winning Stag’s Leap. In its wake, the way in which she writes about her shifting experience with love is sharp and painful. “Now I come to look at love / in a new way, now that I know I’m not / standing in its light,” she writes in “Unspeakable.” And although she wants to talk to her husband about this, he wants, instead, “a stillness at the end of it.” In the absence of her “almost-no-longer husband[’s]” love, Olds feels “an invisibility.” Losing her husband’s love creates a radical shift in her world view, too. “When he loved me,” she writes, “I looked / out at the world as if from inside / a profound dwelling.” Olds questions what’s real—“when I thought he loved me, when I thought / we were joined not just for breath’s time, / but for the long continuance”—which is reminiscent of the great intimacy of Olds’ earlier poems. Most heartbreaking is Olds’ confession in “The Flurry”: “I tell him I will try to fall out of / love with him,” she says, “but I feel I will love him / all my life.” In response, Olds’ husband conjures what was once their third thing when he tells her that “he loves [her] / as the mother of [their] children.”

Where Olds’ poetry may be depressingly grounded in what can go so lopsidedly wrong in a marriage, Shapiro’s is comforting in its exposing of what it looks like for a marriage to enter troubling waters but ultimately prevail. Eighteen years into her marriage, she and her husband visit a couples’ counselor. “I feel M. next to me on her sofa,” she writes. “His body is my home. Yet lately, I have had flashes, unbidden moments in which I wonder who the hell he is. I secretly fear that I’ve been wrong about him.” Considering M.’s body as “home” feels like a subdued version of the intimacy Olds expresses, and yet Shapiro’s confession of fears—here on the published page—becomes another way of writing about intimacy. Up until this point, we’ve primarily seen M. as “home,” but Shapiro isn’t afraid contemplate whether M. is an inadequate, and possibly the wrong, spouse. “What promises did M. and I make to each other on our wedding day?” she asks. “What promises have we broken? And what promises have we kept?”

Ups and downs arise in Hall and Kenyon’s marriage too. After so many idyllic afternoons spent at their beloved pond, “one summer, leakage from the Danbury landfill turned the pond orange. It stank. The water was not hazardous but it was ruined. A few years later the pond came back but [they] seldom returned to [their] afternoons there.” Hall admits, “Sometimes you lose a third thing.” Fortunately, Hall and Kenyon’s other third things, poetry in particular—in addition to their honesty with each other—kept them afloat. “Even when Jane was depressed, I never praised a poem unless I meant it,” Hall writes. “I never withheld blame. If either of us had felt that the other was pulling punches, it would have ruined what was so essential to our house.” In the end, what most bound them together, what was most intimate to them, was poetry. “[W]e lived in the house of poetry, which was also the house of love and grief,” Hall describes, “the house of solitude and art; the house of Jane’s depression and my cancers and Jane’s leukemia.” As Kenyon lay dying from cancer, Hall worked on “Without,” and “[e]ven in this poem written at her mortal bedside there was companionship.” So while Olds’ intimacy is compelling in its sheer depth and surprise, and Shapiro’s marriage is captivating in its grittiness, trials, and honesty, it’s Hall’s marriage that most soothes me in the end—that enduring third thing that gathered him and Kenyon together until death, a vow holding them together even as their bodies let them go.

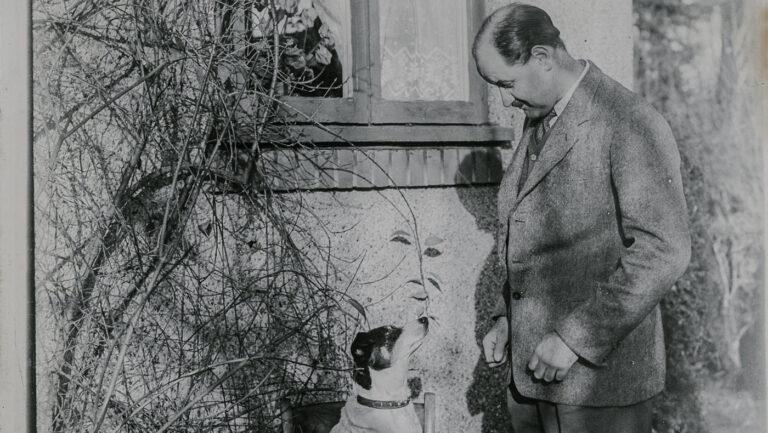

Photograph by Paul Gagnon