Guest post by Scott Nadelson

My ancestors emigrated from Sweden to Minsk sometime in the eighteenth century, most likely to escape restrictive anti-Jewish property laws. But there’s a legend in my family that accounts for the move differently. According to the story, which is usually told with a smirk that suggests no one takes it seriously, our patriarch was a Stockholm horse thief who, after being caught in the act of raiding a rich merchant’s stables, was chased across the Baltic Sea.

It’s a fairly ludicrous story. Whoever heard of a Jewish horse thief? Or a Jew having anything to do with a horse, for that matter? Still, as a child, the story captivated me. It was romantic and dangerous, and it gave me a sense of possibility: Yes, I was shy and undersized and terrified of the world, but somewhere in my blood was recklessness and courage and an adventurous spirit I hadn’t yet tapped. Life doesn’t always have to be the way it is, the story seemed to suggest; there are other lives waiting to be lived.

The story may also have established my literary taste early, priming me to identify with the anti-hero, the failed striver, the hapless criminal. Now it sounds to me like something out of Isaac Babel or Chekhov–not just the horse thief’s flight, but the child dreaming himself in the thief’s saddle, imagining a treacherous nighttime ride, the horse heaving beneath him, furious hooves clattering over cobbles, shots ringing out behind.

I was recently reminded of this story while re-reading Chekhov’s “The Horse-Stealers,” which to my mind is a masterpiece on the level of “The Lady with the Dog” and “Gooseberries,” though less frequently anthologized. It’s one of Chekhov’s strangest stories, and most haunting, and as I read it this time what struck me was how perfectly it captures the unexpected exhilaration and freedom I’d felt as a child hearing about my outlaw forebear. On the surface the story has quite a lot of drama, especially for Chekhov: Yergunov, “a hospital assistant […] known throughout the district as a great braggart and drunkard,” gets lost in a snowstorm, and takes refuge at a country inn; he drinks with a band of thieves, one of whom steals his borrowed horse; he fights with and tries to bed the lovely young innkeeper, who knocks him over the head and steals the purchases he made for the hospital; he loses his job and ends up homeless.

The heart of the story, though, comes in a moment when this elaborate and energetic plot is briefly suspended, a moment of what I like to think of as dramatic observation. The plot–at least in terms of event and consequence–wouldn’t be any different without this moment, whose sole purpose is to explore Yergunov’s character and alter his perspective. At the same time, the moment of observation and its effect on Yergunov is what the story is really about; the actual plot is how the character’s view of the world and of life change as a result of what he sees.

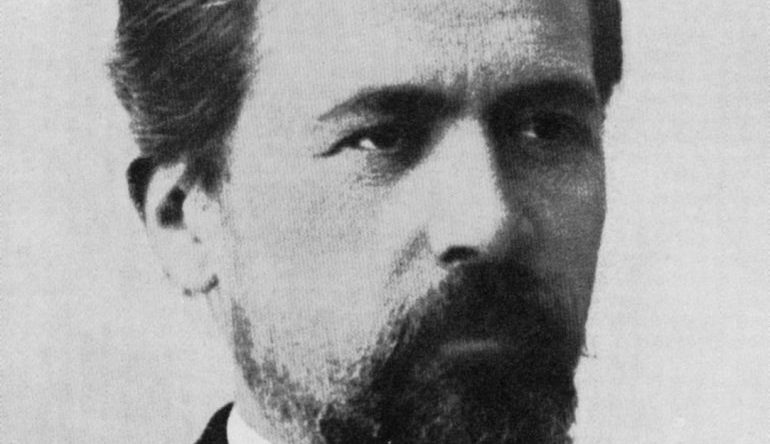

Chekhov in 1889, a year before he wrote “The Horse-Stealers”

Through the first half of the story, Yergunov tries to insinuate himself into the company of the thieves, bragging about himself and drinking too much, but they ignore him. He is envious in particular of “the dark fellow Merik,” who “gave himself the airs of a bravo” and is the object of the innkeeper Lyuba’s admiration. After dinner, one of the thieves starts playing music, and the narrator makes us aware of how out of place Yergunov is among his company: He “could not make out what sort of song [the thief] was singing, and whether it was gay or melancholy, because at one moment it was so mournful he wanted to cry, and at the next it would be merry.” The song is entirely unfamiliar to him, to the extent that he doesn’t know at all how to feel about it, and its strangeness sets the stage for his encounter with the unknown. He has begun a descent into the realm of mystery, embodied in the lives of these thieves.

Yergunov, made entirely passive by the strange music, sits and watches as

Merik suddenly jumped up and began tapping with his heels on the same spot, then, brandishing his arms […] moved on his heels from the table to the stove, from the stove to the chest, then he bounded up as though he had been stung, clicked the heels of his boots together in the air, and began going round and round in a crouching position.

The description of Merik’s dancing is wild and strange, too, and in the way it’s presented to us–as a list of separate actions, without explanation–we get the sense that Yergunov doesn’t understand this any better than he does the music. In fact, Chekhov’s narrator doesn’t ever call it dancing, and it’s not clear that Yergunov even sees it as such. Rather, the sentence could just as easily be describing Merik’s being possessed by an evil spirit, his actions seemingly out of his control.

In this passage, it’s the language that gives us the most insight into Yergunov’s perspective, as we don’t yet have access to his thoughts. And the language grows increasingly colorful, almost surreal, as Yergunov watches what unfolds:

Lyubka waved both her arms, uttered a desperate shriek, and followed him. At first she moved sideways, like a snake, as though she wanted to steal up to someone and strike him from behind. She tapped rapidly with her bare heels as Merik had done with the heels of his boots, then she turned round and round like a top and crouched down, and her red dress was blown out like a bell.

In three sentences, Lyuba turns from desperate to sly and snakelike to whimsical as a toy. As with the music, the emotional register changes from moment to moment, and once again Yergunov doesn’t know how to feel about it. The dance is sexual, and comic, and then even dangerous, as “Merik, looking angrily at her, and showing his teeth in a grin, flew towards her in the same crouching posture as though he wanted to crush her with his terrible legs.” Finally, the description takes a turn toward the magical, as Lyuba “jumped up, flung back her head, and waving her arms as a big bird does its wings, floated across the room scarcely touching the floor.”

Only then does the narrator give us a glimpse into Yergunov’s thoughts, and what we hear comes as a surprise; though he has witnessed the danger in the dance, and sensed the possibility of violence in the spark between Merik and Lyuba, now he registers only desire and awe: “‘What a flame of a girl!’ thought Yergunov, sitting on the chest, and from there watching the dance. ‘What fire! Give up everything for her, and it would be too little.'” But his emotions, too, quickly change, in the next paragraph turning to regret

that he was a hospital assistant, and not a simple peasant, that he wore a reefer coat and a chain with a gilt key on it instead of a blue shirt with a cord tied round the waist. Then he could boldly have sung, danced, flung both arms round Lyuba as Merik did.

Despite all his bragging, he doesn’t think much of himself; his life is painfully restricted, and he has glimpsed the possibility of freedom in the wild, unfettered life of Merik and the thieves.

This scene is a glimpse into forbidden territory, into the violence of desire, but Yergunov isn’t shocked by what he sees so much as mesmerized and seduced by it. During the dance, Lyuba’s necklace breaks, and the beads scatter all over the floor. And then comes the strangest, most disturbing moment of the scene; after

Merik stamped for the last time […] Lyuba sank on to his bosom and leaned against him as against a post, and he put his arms round her, and looking into her eyes, said tenderly and caressingly […] ‘I’ll find out where your old mother’s money is hidden, I’ll murder her and cut your little throat for you, and after that I will set fire to the inn […] People will think you have perished in the fire, and with your money I shall go to Kuban.

Lyuba doesn’t shrink away from her lover’s threat, but “only looked at him with a guilty air, and asked, ‘And is it nice in Kuban, Merik?'”

Observing Lyuba’s desire for a man who has just threatened to kill her, Yergunov doesn’t reject Merik’s model, or question the sense of freedom he has imagined in the thieves’ lives; instead, he continues to envy i

t, and later, after Merik has stolen his horse, he tries to enact a similar violent seduction of Lyuba. He threatens her, saying that if she doesn’t tell him where his horse is he’ll “knock the life out of her.” When she doesn’t respond he “seized her by the shift near the neck and tore it. And then he could not restrain himself, and with all his might embraced the girl.” But Yergunov is not Merik, and instead it’s Lyuba who, “hissing with fury […] hit him a blow with her fist on the skull.”

By the end of this evening, Yergunov loses everything, but what makes the story so unusual and, at least to me, thrilling, is that he doesn’t end up thinking differently about Merik and the other thieves as a result; in fact, the freedom and forbidden desires that seduced him at the inn continue to awe him even after he has become destitute. What he has witnessed, in fact, sparks a profound train of thought at the story’s end; he wonders not only about the restrictions of his own life, but of human life in general: “Why do the sober and well fed sleep comfortably in their homes while the drunken and the hungry must wander about the country without a refuge?” he asks himself. “Whose idea was it? Why was it the birds and the wild beasts in the woods did not have jobs and get salaries, but lived as they pleased?”

Yergunov’s confrontation at the inn brings him to reckon with existential questions that would otherwise never have entered his mind. As difficult as his life has now become, he has arrived at a kind of freedom that justifies the suffering he has gone through to find it; he no longer takes for granted that he, or anyone, should live a particular way, restrained by the conventions of a constructed society, allowing desire to be suppressed by fear. In the image of the horse thief, the world has opened up to him–as it did for me as a child, though more complexly–revealing its possibilities, and even after all he’s been through, he “reflected how nice it would be to steal by night into some rich man’s house.”

This is Scott’s eighth post for Get Behind the Plough.

Images from: http://newtownreliance.org/ and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anton_Chekhov.