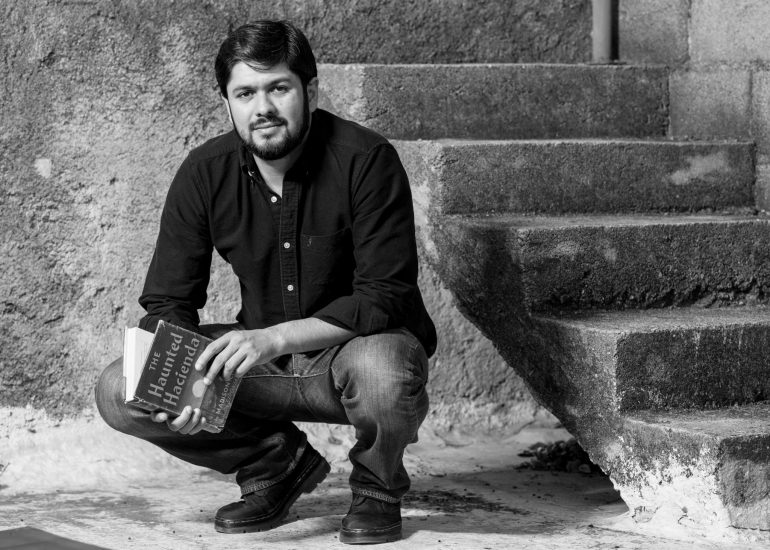

Editorial Argonáutica: A Tiny Interview With Efrén Ordóñez

Editorial Argonáutica is the brainchild of Efrén Ordóñez and Marco Alcalá, both accomplished writers and translators in their own right who decided in 2015 that the world needed a publishing house that would be global in its outlook and that would celebrate the translation and promotion of writers whose work would never cross borders otherwise. Just one caveat: it had to be based in Monterrey, Nuevo León, (far from the literary poles of Mexico City and NYC), a Mexican city best known for being the industrial dynamo of northern Mexico, but also for its deep and significant cultural reach into Texas. Of course, this mission has come to take on incredible significance with the backdrop of contemporary geopolitics between the US and Mexico as well as with the release of their first books from their Polifemo series: Mark Haber’s Melville’s Beard/Las Barbas de Melville and Scott Esposito’s Latin American Mixtape/Mixtape Latinoamericano Here I talk with Efrén Ordóñez about creating a literary space in Monterrey, Mexico that keeps the dialogue open between Mexico and the US, as well as the pressures of translations and what’s ahead for the press.

Daniel Peña: One of the unique things about Editorial Argonáutica is that it’s based out of Monterrey, Nuevo León, which is a major industrial city in Mexico, but also a very rich liminal space and link between Mexican and American culture. Could you talk a little about the concept of Editorial Argonáutica and the ideas that drive the press?

Efrén Ordóñez: When we first came up with the idea of starting our own publishing house, we wanted to have an identity. During a long conversation, we kept falling back to the idea of translation, as we had an interest of the similar projects happening in the United States, and we had talked about Mexican readers not knowing anything about serious contemporary writers from the US, especially those living near the border. Aren’t we supposed to have similar ideas? Could there be a dialogue between our books without us knowing? Also, I have been translating as a day job since 2008, so the idea of translating was very natural too.

Argonáutica came to fruition around the same time as the threat/idea of Trump’s wall (Brexit came next). We could foresee that the segregation of cultures would permeate to the other side of the border. It wasn’t just some faction of US people wanting to kick immigrants out, but Mexicans living in Mexico turning their backs on an entire country too. For us, putting everyone in the US in the same basket was basically the same thing. So we thought about building a literary bridge between our cultures. A writer living in Texas and another living in Oakland. One was fiction, the other one a book about Latin American writers, written by an author who had lived in Latin America for nearly two years. To make things more interesting, we chose to give the translator’s voice the same importance as the author. Granted, the text is the author’s, but the fact that the books are bilingual and the translator’s name is there on the cover gives a sense of a dialogue taking place on the book’s pages.

DP: You’re talking, of course, about Mark Haber’s Melville’s Beard/Las Barbas de Melville and Scott Esposito’s Latin American Mixtape/Mixtape Latinoamericano, which are both incredible books and feats of translation in their own right. As the first books from your press, how do you envision those works contributing to that ever-complicated dialogue between Mexicans, Americans, and their respective governments?

EO: Right. I think each can work in their own way. With Scott’s book, I expect people in Mexico (or Latin America) to know that there’s an interest, and enthusiasm in what we have to say. It is not just an interest in tourism, folk, the colors and sights that we all know foreigners enjoy, but an interest in the way we think and write, on the way actually see the world. Mark’s book is a collection of short stories that don’t deal with Latin American issues, but with the absurdity of us as humans. I feel that by using a contemporary author (from Florida, living in Houston), a Latin American reader can understand a unique perspective of society as a whole, and in fact find a lot of similarities between our cultures. We are all humans.

DP: As a translator, you have an incredible responsibility to not only “get it right,” so to speak, but shape and facilitate a larger conversation between cultures. Do you feel like the translator shapes that conversation as much as the writer? If so, what would you say is the most important conversation right now?

EO: I think so. The translator has to “get it right,” to understand the writer, to understand its context (that of his writing) and also to be careful not to lose all of that when turning it into another language. If the translator is lazy, there’s no shaping, just a mechanical work that could very well be done by some software. In a way, before the reader even gets a chance to “reply” to what the author has to say, the translator does it first. I think the most important conversation right now has to do with each culture’s recognition in one another, and the understanding that (and I’m thinking on Scott’s book) we are being looked at in a whole different way that most of us thought.

DP: You’ve got me thinking about that a lot lately, how there’s a certain responsibility among writers in the border regions to salvage this deep and significant relationship between the US and Mexico. In the end, Texas (which was once part of Coahuila) is still very much culturally a part of northern Mexico—Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, Chihuahua, etc.—as is much of the American Southwest. Our little corner of the world is mostly out of the purview of the literary epicenters of New York and Mexico City. While the rest of the literary world is doing the commerce thing, there is very much a real mission of cultural diplomacy underway among border writers and publishers. Do you foresee the work you’re doing taking on a deeper geopolitical/geoliterary significance as your press grows? Do you foresee literature of northern Mexico/the American Southwest taking on deeper global significance than it enjoys right now?

EO: I don’t know how far our work will go, but I certainly expect it to have some sort of resonance. As you said, both the north part of Mexico and the American Southwest are definitely resisting the literary centralism in their own ways. If we achieve a true dialogue between writers, readers, and publishers, I know we can either start or strengthen the idea of being all part of the same region, and in that way show that there’s hope for eliminating all kinds of borders.

I think both literatures can and will find points of reference and expand to the entire world. And I don’t think it has to do with the clichéd themes (narcos, borders, etc.), that can, should, and will be there, but with more universal concerns written from a specific region.

DP: What’s next for Editorial Argonáutica? What are you working on right now?

EO: Right now, we’re working to take our first two books wherever we can. Independent bookstores mainly, since that is something we love. We had three events this month: Brazos Bookstore, Deep Vellum Books, and Diesel, A Bookstore. We are huge supporters of places like these, and we want our books to be there on their shelves. We also visited The Wild Detectives in Dallas and were impressed with the atmosphere. And we’re planning an event in Monterrey next month as well.

Also, we’re evaluating what our next books will be. We have some ideas, but we want to take some time during the summer to sit and read a lot, to talk to authors and translators, hear them out and try to make their projects happen. We want to publish three or four books next year, using different language combinations (not just English and Spanish), and we are sure it will happen.