Elizabeth Bishop’s Eczema

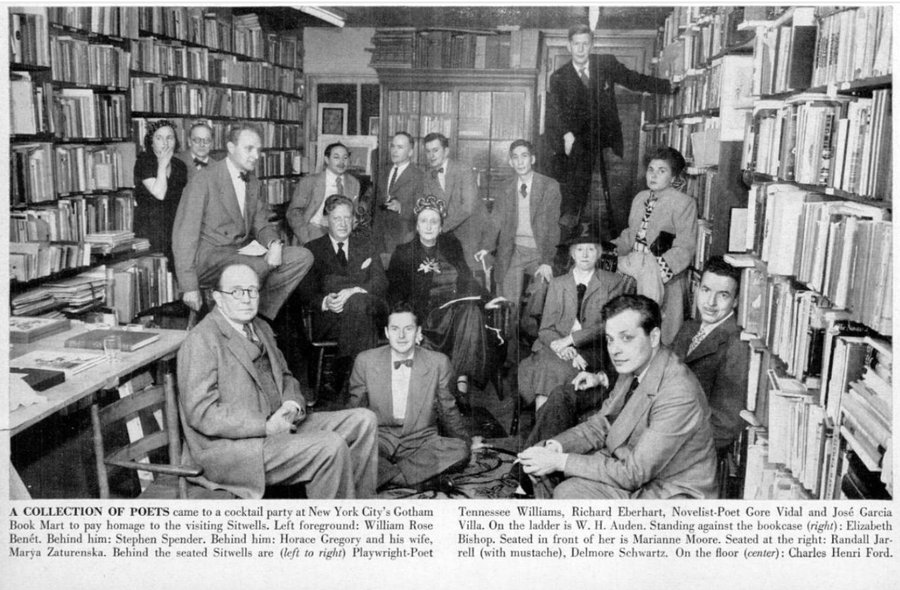

Writing about the American poet Elizabeth Bishop, as I have done for more than twenty years, one constantly hesitates over how much time (if any) to spend on biography. For most of her career, beginning as High Modernism hit its stride in the 1930s and concluding as the Confessional moment petered out in the late-1970s, Bishop was known for not being known, a “writer’s writer’s writer” in John Ashbery’s witty formulation, a “poet’s poet” in James Fenton’s more conventional revision of the phrase. Bishop knew and was often friends with nearly all of the poets a twenty-first century reader might time-travel to meet. She interviewed T. S. Eliot as an undergraduate. She met and became close friends with Marianne Moore after being introduced to her outside the reading room of the New York Public Library. In the famous 1948 Gotham Book Mart photograph of poets gathered at a cocktail party to honor Edith Sitwell’s visit to the US, Bishop is captured leaning against a bookshelf next to Moore and just in front of W. H. Auden. This was the same year that she met Robert Lowell who would later describe not proposing to her as “the might have been for me.” Bishop’s other encounters with poets were equally memorable. She met Pablo Neruda climbing a pyramid in Mexico, was a regular visitor to Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeths Hospital while Consultant in Poetry (now Poet Laureate) in Washington, D.C., and was the recipient of several fan letters from Anne Sexton.

Although Bishop knew and was often close to these poets, she never seemed part of any particular group or movement. Her position in the Gotham Book Mart photograph, off to one side, feels correct. Too young to be a Modernist, too old to be a Confessional, some critics have wondered whether she was in fact a Romantic or at least a post-Romantic poet. Others have called her “mid-century” as if her natural home were somewhere in the middle, borrowing a little from many traditions, not one. In aesthetic terms, this term feels like a better fit too: a formalist who could write personal poetry but only on her own terms and only towards the end of her career.

Bonnie Costello, in a memorable phrase, reflects on what she terms Bishop’s “impersonal personal”:

She kept a great deal to herself, but for more than a decade criticism has been rummaging through her closets…Art becomes a circular activity in which source and end narrowly converge. But Bishop’s poetic intelligence is not so reflexive. Her poems do not so much veil or transmute the personal as expose the categories of “personal” and “impersonal” to scrutiny.

Costello is harder on biographically inclined criticism than is perhaps necessary. She is certainly harder than Bishop herself who had a significant biography section in her personal library and often recommended consulting a poet’s letters when attempting to understand their poetry. She taught a course on correspondence at Harvard, celebrating her belief in letters “as an art form.” She also had several stabs at biographical readings herself, such as the following comments on Flannery O’Connor’s fiction:

The writing is so damned good compared to almost anything else one reads—economical, clear, horrifying, real. I suspect that this repetition of the uncle-nephew, or father-son, situation, in all its awfulnesses, is telling something about her family life—seen sidewise, or in distorted shadows on the wall.

Bishop’s analogy for the relationship between biography and writing is indebted to visual art. It reminds me of the dreamscapes of Giorgio de Chirico, one of her favorite painters. She moves from the work to the life in a sentence, suspecting O’Connor of “telling” us “something” about herself without ever quite finding the evidence for it. The author’s life is glimpsed in a fleeting image, “seen sidewise,” or, in a typical Bishop correction of her first idea, “in distorted shadows on the wall.”

General readers of American poetry probably know Bishop as the author of “One Art.” It is a poem well known enough to be cited in full in two Hollywood movies: In Her Shoes (2005), featuring Cameron Diaz and Toni Collette, and Still Alice (2014), starring Julianne Moore and Kristin Stewart. College students will be familiar with other poems and perhaps biographical details, including her increasing importance as a queer poet. Her alcohol use disorder is often there in the shadows, her asthma too. But what about her eczema, the first of three lifelong conditions to develop in childhood and the one that quite literally affected her ability to write?

*

In a poignant chronology that Elizabeth Bishop wrote for her psychiatrist, Dr Ruth Foster, in 1947, we find several references to childhood illnesses, none of which are named. Under the entry for 1916, she remembers being “very sick that winter.” The next mention of sickness is a decade on. “I was supposed to go to Walnut Hill in the fall of 1926,” she states, “but they would not accept me because of my health.” In 1961, Bishop filled in some of what happened between these dates in the short story “The Country Mouse.” We know, for example, that she developed severe bronchitis in winter 1916. The year after, in October 1917, she was taken from her maternal grandparents’ home in Great Village, Nova Scotia, to live with her paternal grandparents in Worcester, MA. The move did not improve her health. If anything, it made it worse. “First came eczema, and then asthma.” Bishop gave further details about this time in a series of letters to Anne Stevenson in 1963 and 1964:

I had already had bronchitis and probably attacks of asthma—in Worcester I got much worse and developed eczema [sic] that almost killed me and had the beginnings of St. Vitus Dance along with everything else—One awful day I was sent home from “first grade” because of my sores—and I imagine my hopeless shyness has dated from then.—In May, 1918, I was taken to live with Aunt Maud; I couldn’t walk and Ronald carried me up the stairs—my aunt burst into tears when she saw me. I had had nurses etc.—but that stretch is still too grim to think of, almost.

The letter to Stevenson repeats one word twice: almost. Childhood illness “almost killed” her. The stretch of time is “still too grim to think of, almost.” Summing up events at the end of the letter, we find it again: “Although I think I have a prize ‘unhappy childhood,’ almost good enough for the text-books—please don’t think I dote on it.—Almost everyone has had, anyway.”

“Almost” does a lot of emotional work here. In its first mention, it places the child close to death. On its second appearance, that physical closeness to death is replaced by tonal distance. Bishop keeps the memory of it at arm’s length, or at least as far away as an awkwardly inserted comma permits. The concluding statement paradoxically both owns up to this pain and universalizes it. While awarding herself a “prize” for surviving childhood, she immediately downgrades herself to a runners-up spot. It is “almost” good enough for the text-books, not quite good enough. On further reflection, perhaps even a runners-up prize is generous. After all, Bishop suggests, “almost everyone” has had an “unhappy childhood,” haven’t they?

One can hear echoes of D.W. Winnicott’s famous phrase about being a “good enough mother” here. Winnicott coined the phrase in his 1953 book, Playing and Reality. Bishop’s own mother, Gertrude May Bulmer, was many things to her. Canadian biographer Sandra Barry offers the most elegant and nuanced summary:

Gertrude was tide. Gertrude was time. Gertrude was voice. Bishop learned about ebb and flow, now and then, sound and silence from her mother. The love at the heart of Gertrude’s life and relationship with her daughter rippled out in Bishop’s own life and art. The loss of this love was a painful legacy and a strange liberation for Bishop—their relationship was complex, fraught, contradictory, and mysterious; it cannot be reduced to a vague speculation or reductive conclusion.

Could Bishop ever have described Gertrude as “good enough”? For most of her childhood, she was simply not there. In the chronology Stevenson prepared for her monograph on Bishop’s poetry, Bishop agreed on Stevenson including the following entry: “1916. Mother became permanently insane, after several breakdowns. She lived until 1934.” “I’ve never concealed this,” Bishop added, “although I don’t like to make too much of it. But of course it is an important fact, to me. I didn’t see her again.” Although there is no evidence that Bishop read Winnicott directly, she was certainly aware of the broad outlines of his work and especially the widespread currency of that phrase. In employing it a decade later in a letter, she adjusts the focus from the mother being “good enough” to look after her child to the child having grown up to look after herself, observing the effects on the adult now rather than the child then. The act of separation is not entirely believable. The child’s loss has not gone anywhere.

*

One of the most obvious effects of Bishop’s childhood was the eczema that first developed in 1917, recurring throughout her life until her death in 1979. In her letter to Stevenson, almost dying provides her with an almost perfect unhappy childhood, albeit one almost all of us may have experienced, or so Bishop claims. Her final “almost” is the most generous if most unconvincing use of the word in the letter. Most readers aware of Bishop’s childhood experiences probably consider themselves lucky in relation to her. In acknowledging our potential pain and underplaying her own, she inspires sympathy without ever asking for it directly.

Eczema is the name for a group of skin conditions that cause dry, irritated skin. Given its appearance in early childhood, it is likely that Bishop had atopic eczema. People with atopic eczema alternate between periods when symptoms are more severe and periods when symptoms are more or less under control. But it never really disappears. According to the UK’s National Health Service website: “The exact cause of atopic eczema is unknown, but it’s clear it is not down to one thing.” Food allergies and sensitivities to domestic animals play a part. It can run in families and often develops alongside other conditions, such as asthma. Symptoms can be triggered by environmental factors like a change in season or a rise in pollen, or psychological factors like overwork or stress. Sadly, there is no cure. As the National Health Service guidance also points out, it may be “difficult to cope with physically and mentally.”

Biographers have tended to follow Bishop’s example in mentioning eczema once or twice before moving on to other matters, as if it were a condition she left behind in childhood. Brett Millier is far more interested in writing about Bishop’s alcohol use disorder, for example. Megan Marshall spends more time on Bishop’s relationships. Barbara Hammer concentrates on where Bishop lived and which residences became homes. Colm Tóibín identifies Bishop as a queer icon alongside English poet Thom Gunn.

Thomas Travisano is the first biographer to take Bishop’s eczema seriously. In the first paragraph of his biography, Love Unknown: The Life and Worlds of Elizabeth Bishop (2019), Travisano draws attention to the extent to which “severe and lasting autoimmune disorders” punctuate Bishop’s life story at regular intervals. For Bishop, Travisano writes, “memory was not just visible or auditory. It was also somatic—that is of the body. She saw memories in her mind’s eye and recollected them in her ear, but she also felt these memories, through involuntary shudders in her body, particularly in the diaphragm, a fact of no little importance given her lifelong susceptibility to asthma.” Bearing in mind her eczema, one might add that she also felt memory on and under her skin, in the rashes and sores that flared up whenever and wherever she remembered abandonment or distress.

“The Country Mouse,” drafted in the early 1960s but not published until after her death, contains the most extensive account of her childhood illnesses and a shadowy if unformed sense of how they affected her adult life and writing. Her identification with social outsiders—all of her grandparents’ employees, except Ronald the chauffer, were Swedish—began to take root during her time in Worcester. These live-in employees, their status as less than family members but more than paid workers analogous to Bishop’s own status as a guest in other people’s homes, were easier to be around and talk to than her father’s relatives. The family dog, Beppo, was probably her best friend, his “delicate stomach” and general nervousness a reminder of her similar physical state. Bishop recalls exploring the house “like a cat.” But having the freedom of the house did not mean she felt at home there. Gradually, as she became ill again, even this relatively limited freedom was curtailed: “At nights Beppo and I scratched together, I in my bed and he outside my door. Roll and scratch, scratch and roll. No one realised that the thick carpets, the weeping birch, the milk toast, and Beppo were all innocently adding to my disorders. By then I was so sick that I had my breakfast in bed.”

Travisano believes that Bishop was “dangerously ill” at this point. “Bereaved, uprooted, intimidated, deeply unhappy, and with her lungs weakened by that severe case of bronchitis suffered the year before, Bishop experienced a violent case of eczema and what doctors feared might be a fatal case of asthma, soon followed by the symptoms of St. Vitus’s dance.” “The Country Mouse” reads more like a doctor’s report than a memoir of childhood. “First came constipation, then eczema again, and finally asthma. I felt myself aging, even dying.” This is, unsurprisingly, one of the few occasions in Bishop’s writing career when she remembers herself unselfconsciously crying. “At night I lay blinking my flashlight off and on, and crying. As Louise Bogan has so well put it: ‘At midnight tears / Run into your ears.’”

Tears are rationed in her writing from this moment on. It is almost as if once she had let herself cry, she would not do so again. In almost every poem in her final collection, Geography III (1976), the poem’s speaker approaches breakdown before just about recovering their composure. In “In the Waiting Room,” the effect of overhearing “a cry of pain” is dramatic, but a list of questions about where the cry comes from and what provoked it keep her own emotions under check. In “Crusoe in England,” the poem’s final lines—“And Friday, my dear Friday, died of measles / seventeen years ago come March”—imply that Crusoe is on the edge of tears, but not quite there yet. The poem comes to a close just in time. In “The Moose,” family loss is expressed via what Bishop describes elsewhere as an “Indrawn Yes”: “A sharp, indrawn breath, / half groan, half acceptance, / that means ‘Life’s life that. / We know it (also death.).” Bishop’s most famous poem, “One Art,” compresses life’s disasters into the tight form of a villanelle, stuttering on the final word to complete the poem but nevertheless still putting it down in writing. “Five Flights Up,” the last poem in the book, describes the familiar feeling of not wanting to wake up after “yesterday” but being persuaded to do so by a cheerful dog with no sense of shame.

*

“The Country Mouse” ends, as many of Bishop’s poems end, with an initially selfish perspective on life rejected or at least revised. An experience in a dentist’s waiting room (the same experience she writes about in “In the Waiting Room”) causes her to see the self as at first unique (“I felt I, I, I”) and then as nothing special (“I was one of them too”):

I felt I, I, I, and looked at the three strangers in panic. I was one of them too, inside my scabby body and wheezing lungs. “You’re in for it now,” something said. How had I got tricked into such a false position? I would be like that woman opposite who smiled at me so falsely every once in a while. The awful sensation passed, then it came back again. “You are you,” something said. “How strange you are, inside looking out.”

It is tempting to see this moment as a Romantic epiphany, the lonely body at the beginning of the story exchanged for the transcendent mind able to rise above material matters, much as Samuel Taylor Coleridge is able to go on an imaginative journey with his friends even as he remains physically imprisoned in a lime-tree bower. If so, the epiphany is brief and ends abruptly. Bishop cannot escape the “scabby body” and “wheezing lungs.” She realizes that strangers have these symptoms too, that she is “one of them,” and equally that they are like her too. “One,” in this case, is multiple, an impersonal pronoun that means “I” and “you” and “we.” Read the line again—“I was one of them too”—and it suggests not just that Bishop is like other people but that every person experiences doublehood in some shape or form. We are one person, but also two.

The realization of her body’s doubleness, its uncontainable and uncontrollable nature, is exciting and terrifying. “Inside looking out,” she both is and is not the “scabby body” that frames these thoughts. Eczema, in other words, only partly defines her. Indeed, it probably permits her to see what other non-scabby bodies frequently miss.

Bishop’s paternal relatives showed little empathy towards the young child struggling to survive in their oppressive house. In May 1918, just seven months after moving from Nova Scotia to New England, she was moved again, to Revere, MA, to live with her aunt Maude Bulmer Shepherdson and uncle George Shepherdson. Bishop was happier living with her mother’s sister, though in the letters to Dr. Ruth Foster she revealed that she had been sexually and physically abused by her uncle from the age of eight until she was fourteen or fifteen years old. Her father’s family saw little improvement in Bishop’s health over the next decade. In February 1928, the month Bishop turned seventeen years old, her aunt Ruby wrote to Walnut Hill School to complain about her niece’s progress: “Elizabeth is rather spoiled and has not been made to do many things…She was always a sort of pathetic child having to fight asthma and eczema ever since she was a baby. I can only hope that she will do better as time goes on.” There is no evidence that Bishop ever saw this letter, but she must have been aware of her aunt’s disdain at her physical state. In “Exchanging Hats,” a poem unpublished in Bishop’s lifetime, aunts and uncles who try on each other’s “headgear” are figures of ridicule rather than fun. Uncomfortable in their own skin, the aunt’s “avernal eyes” are especially poisonous. Bishop’s satire against those who look down on others is even more to the fore in the late poem, “Pink Dog,” in which a pregnant dog with scabies is singled out by passers-by. Bishop identifies, as elsewhere, with the depilated dog. She knew from a young age what it was to be stared at. As in many of her poems, animals are frequently kinder than human beings, even if they happen to be family members.

Travisano describes asthma and eczema as Bishop’s “chronic companions.” Her chronic reaction to eating the fruit of a cashew nut in December 1951 contributed to one of her most significant life-changing decisions: the postponement of a planned trip around South America to live permanently with Lota de Macedo Soares. Bishop’s most complete account of what happened occurs in a lengthy letter to her New York physician, Dr. Anny Baumann, a letter that interestingly sheds light on her experiences as a child:

After about a week eczema appeared, very bad, the worst on my ears and hands—just the way I had it as a child but I’ve never had it since. I finally got sick of being stuck with so many things like St. Sebastian and just stopped everything completely—and now I’m all right, except for a few patches of eczema, not bad, and the asthma that continues although now I only have to take 3 or 4ccs. Of adrenaline in the course of every night. I haven’t been able to write or type much because of my hands.

Yesterday I felt so much better I started to wash my hair and fainted. My poor hostess got so alarmed that she started to faint—surely the perfect hostess. It was very funny. Fortunately everyone has been extremely kind. All the friends and relatives come with suggestions and their own bottles of pills, etc., and I had a hard time dissuading my hostess from telephoning you the worst of it.

Bishop’s “perfect hostess” was Lota. For her birthday in February 1952, Lota had engineered the purchase of a toucan who Bishop christened Uncle Sam. The same month, Lota invited her to stay in Brazil for good and promised to build her a studio. Bishop’s epithet for Lota, “my poor hostess,” recalls Virginia Woolf’s modernist novel Mrs. Dalloway in which the eponymous central character is both admired and ridiculed for hosting the perfect party. It is also a novel in which two women, Clarissa and her friend, Sally Seton, fall in love. Was Bishop already confessing romantic feelings for her “perfect hostess” in this letter?

On Valentine’s Day, in a letter to Marianne Moore, she reflected on the kindness of those who at the point she fell ill were still strangers: “I swelled and SWELLED…I looked extraordinary and it shows how nice Brazilian people can be that it seemed to endear me to them rather than otherwise.” The contrast with relatives like Aunt Ruby must have been striking.

Bishop brought several incomplete manuscripts with her to Brazil. One unfinished piece of writing was a story about her childhood in Great Village, in particular her relationship with her mother. In September 1952, as her asthma attacks increased, Bishop began to try what was then a new anti-inflammatory drug, cortisone. In October 1952, in just a week, she finished drafting two new stories set in Nova Scotia, “Gwendolyn” and “In the Village.” In the former story, Bishop recalls her bout of bronchitis from the perspective of “my usual summer state of good health.” Her “good health” is brought into further relief by her friend Gwendolyn’s diabetes, a condition from which she dies at the story’s conclusion. “She was ‘delicate,’ which, in spite of the bronchitis, I was not.” After Gwendolyn’s death, the child narrator and her cousin Billy decide to bury her aunt’s favorite doll: “I don’t know which of us said it first, but one of us did, with wild joy, that it was Gwendolyn’s funeral, and that the doll’s name, all the time, was Gwendolyn.” Travisano suggests that the wild joy “surely arose from the emotional relief attached to the fact that they might finally complete the process of interrupted grieving that had been forestalled by the young pair’s exclusion from the village’s ritual of mourning.” It is likely that Bishop was remembering another period of “interrupted mourning,” too: her mother’s death. Gertrude Bulmer died on May 29, 1934. Her aunt, Grace Bulmer Bowers, accompanied Gertrude’s body from Nova Scotia to Worcester where she also met Bishop. There is no evidence that Bishop attended the burial service. Equally, there is no evidence that she did not go. Sixteen years later, Bishop was in a better place health-wise to address these memories, even if the specific memory of her mother’s burial remained taboo. She did not have to be at the burial to imagine it just as she did not have to attend Gwendolyn’s funeral to feel her loss.

If “Gwendolyn” addresses Gertrude’s absence by proxy, “In the Village” deals with it head-on, albeit from the perspective of a child who does not know why her mother is coming and going and why she is so upset. The opening paragraph begins with the sound of a scream that critics nearly always identify as coming from Gertrude’s mouth. Bishop’s friend and fellow poet, Robert Lowell, rewrote this part of the story in a poem and called it “The Scream.” It is, of course, equally plausible to hear this scream in Bishop’s voice as an empathetic response to her mother’s grief at losing her husband and the poet’s own bereavement at both their early deaths:

A scream, the echo of a scream, hangs over that Nova Scotian village. No one hears it; it hangs there forever, a slight stain in those pure blue skies, skies that travellers compare to those of Switzerland, too dark, too blue, so that they seem to keep on darkening a little more around the horizon—or is it around the rims of the eyes?—the color of the cloud of bloom on the elm trees, the violet on the fields of oats; something darkening over the woods and waters as well as the sky.

Putting aside for a moment the scream’s origin, I would like briefly to consider the light effects in the Nova Scotian sky (“too dark, too blue”), in particular the suggestion that the person remembering can somehow not see clearly to the horizon. What is that “something darkening” at the limits of vision? Is it “the color of the cloud of bloom on the elm trees” or “the violet on the fields of oats”? It is almost as if the speaker were looking at a picture of the scene rather than the scene itself. Might this story begin not in the author’s imagination or memory but with her looking at an actual postcard image? Something of this confusion happens in a later Bishop poem called “Poem,” in which a small painting of a Nova Scotian landscape is admired first for its color scheme before the speaker sees through the brushstrokes to an actual Presbyterian church and house with which she is familiar (“Would that be Miss Gillespie’s house?”). A still life becomes life, or at least something close to it. It is a moment of artistic magic, an image mysteriously becoming more that the sum of its parts.

There is another curious effect in the oddly specific question at the passage’s heart: “Is it around the rims of the eyes?” Eczema often affected Bishop’s eyesight. She gave up a job grinding binocular lenses in the US Navy Optical Shop in Key West during the Second World War because the chemicals used in the solution triggered an allergic reaction. Imagining a scene associated with childhood like this, even from a distance, may have been an emotional trigger. As Bishop sees an image of Great Village, even a postcard image, it is easy to imagine the skin around her eyes reacting to the psychological pressure. This might well have caused a fuzziness at the edge of her field of sight, hesitation, at the same time, about what she is actually looking at.

*

The fact that Elizabeth Bishop did not make much of a fuss about having eczema does not mean it was not a fuss to live with. At times in her life, it literally affected her ability to write. She could not grip a pen to write or type. In Brazil, she tested a new medicine that was then risky. She continued to travel when it would undoubtedly have been safer to stay put. And carefully and without much of a plan, in stories more than poems but in poems too, she wrote about her own eczema and other skin conditions that are still more often seen but not heard. At times, the symptoms are very audible in Bishop’s writing. You can hear them in the repetitions of “The Country Mouse”: “Roll and scratch, scratch and roll.” They are there in numerous poems too, in the Man-Moth’s decision to keep “his hands in his pockets, as others must wear mufflers”; in the insomnia of any number of early poems and their repeated desire to “sleep up there”; in the contemplation of the physical effects of cold water in “At the Fishhouses,” in particular the prior knowledge of what it feels like when your bones “begin to ache” and your hand “burn”; in the awkward physicality of a Giant Snail who compares its body to a “decomposing leaf”; in the three adjectives used to describe the New Brunswick woods in “The Moose”: “hairy, scratchy, splintery.”

Considering Bishop’s eczema in relation to her poems and stories is, I hope, different to what Costello identifies as critical closet “rummaging.” Being aware of eczema, a physical and psychological condition that Bishop endured throughout her life, demonstrates how difficult and painful the daily acts of looking and writing could be for her, even before she sat down to think about transforming these experiences into art. To hear and see reminders of her condition in that writing is not to suggest eczema is the defining subject matter of any poem or story, but to acknowledge its pressure on any word or phrase that evokes physical discomfort or embarrassment.

Inside looking out; outside looking in. If eczema is at least in part an external sign of interior pain or trauma, it is also a physical condition that has psychological benefits, not least an ability to notice, recognize, and value vulnerability in others. Bishop commemorates the tricky art of living in a body more often than many of us have noticed, an art we almost didn’t see.