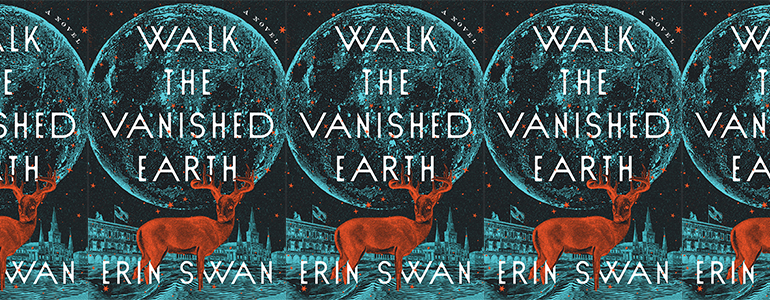

Facing the End of the World in Erin Swan’s Walk the Vanished Earth

Walk the Vanished Earth

Erin Swan

Viking | May 31, 2022

Erin Swan’s debut novel Walk the Vanished Earth begins amidst the blood, guts, and sweat of the Kansas prairie: “He has shot twelve today: two bulls, nine cows, one calf…The afternoon stinks of dropped dung and blood and his own sweat. He mops his face with his handkerchief [and] wonders when his beard will grow.”

The “he” in question is Samson, the future patriarch of the family. We meet Samson as a young Irish immigrant hunting buffalo in the Kansas prairie land in 1873. Swan makes it immediately clear what type of novel this will be—the throat of the buffalo Samson is readying himself to kill, “the single soft spot in town.” And yet there is tenderness too, a young man not yet able to grow a full beard, dreaming of the land he one day hopes to sow and the woman he hopes to wed. From the start, it is clear this is not only a novel of natural disaster, destruction, and dystopia, but also one that shows desire does not end just because the world does.

The story then leaves Kansas, and any semblance of linear story-telling ceases. We jump ahead to 2073, to a young girl named Moon—a person, not the planet—who is Samson’s great-great-great-great granddaughter. She is traversing Mars with two beings who she calls Uncle One and Uncle Two. They are not entirely human (they subsist off dust and communicate non-verbally), but what they are exactly remains unclear. Moon knows nothing of the world beyond Mars, relying on the stories her uncles tell of Earth, a place once teeming with life now dwindled to nothing. The first fourteen years of Moon’s life are spent like this, walking across the red dunes to seemingly no end. No end, that is, until they reach “the dome,” a structure Moon is told was once her home. It is the dream so many on Earth have espoused: life on Mars. A place where humans, in theory, could thrive after our own planet becomes uninhabitable.

Samson and Moon are the beginning and the end of the family tree that outlines this sweeping tale of seven generations. Swan teases out the rest of the family line slowly and methodically, leaving the reader to put together the pieces with each page they turn. (We don’t know where Moon was born or who her mother was until the final third of the book.) Time stretches out and collapses in on itself; we skip one hundred years of history to get to chapters told in years, days, and even hours.

The world in Walk the Vanished Earth begins to crumble in 2017, and it is a dissolution that feels all too familiar. Paul, a descendant of Samson, remembers watching Hurricane Katrina flood New Orleans from his living room in Kansas City, and the current news is no relief, just “the regular litany of horrors. Nature wreaking havoc across the globe. Inept governments pushing weakly against it.” We already know this story—we live it every day—we just don’t yet know how it will end or who we will be when these daily disasters can no longer be ignored.

In Walk the Vanished Earth, Swan imagines multiple possible answers to these questions—a floating city is built in New Orleans after the majority of the earth floods. A society entitled the “Northern Refuge” ships people off to Mars to give birth to the next generation and create a new world, complete with engineered guinea pigs for dinner. A troupe of women treks across the country, avoiding murderous marauders and finding love in their tents. A trio of sailors discovers a Caribbean island community somehow surviving above sea level after every other island has long been submerged.

And while much of the drama of this book centers around natural disasters, Swan acknowledges there will be more than fires and floods to wrestle with as the world ends. People will still fall in love and disappoint each other; children will still long for their mothers and their mothers will still try and fail to protect them. Some of Swan’s most compelling writing considers what it means to be a mother—its burdens, its joys, and the choices that do not really feel like choices. Each of the women she features come to motherhood in different ways—by force, choice, accident, and coercion—and yet they all must contend with the consequences equally. It is no small thing to carry a child, but so much of our world treats it “as though forming a human with the meat of one’s body is merely a matter of carrying.” As I read Walk the Vanished Earth, Americans learned of the upcoming decision to overturn Roe v. Wade—news that comes alongside a nationwide baby formula shortage and ever-increasing rates of maternal mortality. Now more than ever, we’re grappling with what it means to be a mother on a vanishing earth with vanishing choices.

Even through the lens of one family line, Swan’s novel is an ambitious undertaking—the end of our world and the creation of a new one—and it felt, at times, like Swan had to rush to fit it in under four hundred pages. The frequent time jumps were often jarring: as soon as I found my bearings in one chapter, we were jolted into the next, with new people to care about and new rules to follow.

And yet, Swan creates characters so fully lived in, with such detail and heart, that I would have read more if given the chance. As it is, I read the entire book in three days, gripped by the story. It is not an escape, but what is in the world we live in? “This planet exhausts him,” writes Swan of one character. Readers will recognize this feeling, exhausted by the constant onslaught of personal, political, and environmental disasters. What would it look like, Swan appears to be asking, if we could imagine something beyond the “regular litany of horrors?” Can we create something new, beautiful, and lasting in the wake of the world? Swan’s novel suggests we don’t have any other choice but to try.