Facing the Jackpot with William Gibson

After the 2016 presidential election, I had the uncanny feeling that we had veered into a different, darker timeline and were hurtling away from the future I had expected. Suddenly, I could see clearly the country as it really is for the first time: systematically racist, and with a sizable population determined to maintain white supremacist and misogynist hierarchies. At the same time, I felt that what was happening was unreal. The real world was elsewhere, on the other timeline we had split away from, where Hillary Clinton had been elected president and, though things were hardly great, we at least weren’t hurtling toward the nuclear apocalypse I was certain that our president-elect was eventually going to stumble into. For months I lay awake at night and in the still-dark hours of the morning in terror.

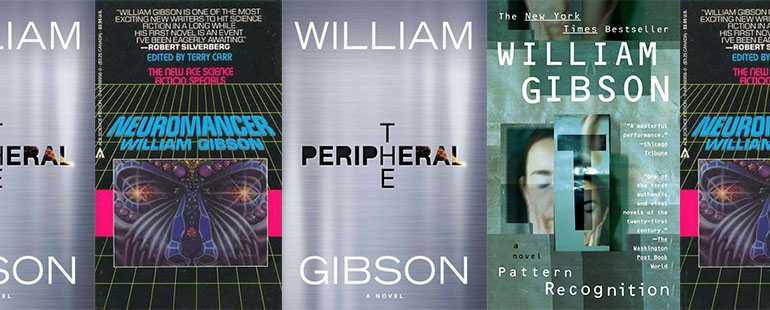

In an attempt to help me assuage this fear and sort through my sense of disorientation, I decided to reread The Peripheral, William Gibson’s 2014 novel that imagines a twenty-second century in which a powerful quantum computer rumored to be located in China has enabled the creation of “stubs,” or alternative timelines. In the novel, characters living in twenty-second-century London—a heavily surveilled city run by phenomenally wealthy kleptocrats and mysterious guilds—interact in a stub they have created with characters living in a mid-twenty-first-century Appalachian town whose economy is based mainly on manufacturing, or “building,” illicit drugs. The interference from the future, which includes gaming the lottery and manipulating international exchanges, leads to a rapid and radical transformation of the fates of the characters in the stub that may help them avoid, at least on their timeline, the slow-moving apocalypse called the “jackpot.”

As twenty-second-century Wilf Netherton explains to twenty-first-century Flynne Fisher, the jackpot was “no one thing”: “multicausal, with no particular beginning and no end. More a climate than an event, so not the way apocalypse stories liked to have a big event, after which everybody ran around with guns . . . or else were eaten alive by something caused by the big event. Not like that.” Triggered mainly by climate change, the jackpot included:

nothing you could really call a nuclear war. Just everything else, tangled in the changing climate: droughts, water shortages, crop failures, honeybees gone like they almost were now, collapse of other keystone species, every last alpha predator gone, antibiotics doing even less than they already did, diseases that were never quite the one big pandemic but big enough to be historic events in themselves.

Over forty years, 80 percent of the human population died; the surviving 20 percent, meanwhile, benefited from the technologies that developed as the slaughterhouse of history unfolded: “cleaner, cheaper energy sources, more effective ways to get carbon out of the air, new drugs that did what antibiotics had done before, nanotechnology that was more than just car paint that healed itself or camo crawling on a ball cap.” Also, of course, the rich got richer, “there being fewer to own whatever there was.”

Flynne’s first reaction upon hearing Wilf’s explanation of what is to come is to ask Wilf what was done with all the bodies (Wilf’s response: “The usual things,” and later nothing; after that, nanobots took care of them). The next day, she tells a friend (who doesn’t know what Flynne has just been told) that her conversation with Wilf was “Either depressing and scared the fuck out of me or sort of how I’d always figured things are?”

In a recent New Yorker profile, Gibson admits his “real trouble” arriving at Flynne’s conclusion (which, one infers, matches his own conclusion about where we’re headed today): “I couldn’t really think about it. I just had to get to the point where I could write it really quickly. Afterward, I looked at it and was just . . . It was the first time I’d admitted it to myself.” Facing the jackpot, admitting its possibility (or likelihood?)—this was why I was compelled to reread The Peripheral in late 2016. I was seeking a way to feel about the future—something other than terror—so that I could endure it.

At the time, the novel didn’t satisfy me as I had hoped. Flynne, for example, takes no time to think about or grieve the jackpot; resilient, resourceful, she keeps moving forward—like the avatar in a side-scrolling video game or, she contemplates at one point, like her veteran brother, who “ignored the crazy, went tactically forward.” A skilled gamer with the tag name Easy Ice, Flynne is nothing like me, whom anxiety often overwhelms. I could never hunt down and kill a brutal SS officer, even in a video game, as she does; her survival skills are not mine. And anyway, given the deus ex machinations of Wilf and his co-conspirators, Flynne might not even be moving forward toward the jackpot, whereas I am (we are) stuck on this one timeline with no interventions (it seems)—benign or otherwise—coming from the future.

Meanwhile, some residents of Wilf’s post-jackpot London dwell in distress on the degraded state of the world, despite not having lived through the jackpot themselves. Wilf is a malcontent with alcoholism, and he regards the past (Flynne’s present) with a romantic longing, fixating, for example, on his vision one night of Flynne’s moonlit lawn. Another character, Ash (full name Maria Anathema Ash), has based her entire persona on mourning the lost past, wearing elaborate Victorian Goth outfits (“Hair the nano-black of the lace at her throat, the bustier of perpetually rain-streaked iron and glass, as if viewed through the wrong end of a telescope, the layered skirts below it like a . . . tutu”) and tattooed all over with the images of “every bird and beast of the Anthropocene extinction.” Their melancholia appealed to me in a way that Flynne’s unattainable cool never could. And yet the form of the novel—a fast-paced thriller with short chapters that alternate points of view—doesn’t allow the narrative to settle into the sadness of these characters, which was what I finally understood I wanted to feel.

And so I found myself rereading Gibson’s 2003 novel, Pattern Recognition, one of my top three favorite books, immediately after rereading The Peripheral. I read Pattern Recognition periodically to tap into its sadness, which is the sadness of the time immediately after the attacks on September 11, 2001 and the beginning of the United States’ forever wars (the book is set in the fall of 2002). Cayce Pollard, its heroine, has become for me an avatar of my twenty-first-century sadness, which began on the day when I stood in Times Square and read on a news ticker that one of the towers had fallen, and which has not left me since.

Cayce is a “coolhunter,” identifying fashion trends for designers, but, like me, she is not herself cool. To be cool, said Jad Abumrad in a 2014 episode of Radiolab, is to face death and nothingness (or, perhaps, the jackpot) with the attitude I am not afraid. Flynne “Easy Ice” is cool. Molly Millions, the mirror-eyed razor girl for hire featured in Gibson’s first novel, Neuromancer, is so cool that I can’t imagine her even conceiving of such a thing as fear. Cayce, on the other hand, is sad, sensitive, and anxious. She is in mourning, having recently lost her father, who went missing somewhere in downtown Manhattan on the morning of the attacks on the World Trade Center; a year later, what happened to him remains a mystery.

Cayce’s skill as a coolhunter comes in part from a peculiar sensitivity: certain brands, logos, and styles give her severe allergic reactions. This sensitivity enables her to identify effective logos for marketing firms. It also limits her wardrobe; she wears only what her friend Damien calls CPUs, or Cayce Pollard Units, which are “either black, white, or gray, and ideally seem to have come into this world without human intervention.” CPUs mainly consist of small boy’s black Fruit of the Loom tees, gray V-neck pullovers made for prep school uniforms, black 501’s with their trademarks removed, a black skirt from a thrift shop, black leggings, a long black tube Cayce calls “skirt thing,” and (her one indulgence) a black Buzz Rickson’s MA-1 bomber jacket. My husband once asserted that Cayce is cool, moving through the world self-contained in her CPUs. I pointed out that she is not so much self-contained as highly defended in her CPUs, unable to tolerate wearing anything else. (I have my own clothing-based sensitivities, and can relate.) Stumbling into a Tommy Hilfiger display at Harvey Nichols makes her sick (“Some people ingest a single peanut and their head swells like a basketball. When it happens to Cayce, it’s her psyche”); a glimpse at the Michelin Man, the first trademark to disturb her (“She’d been six. She’d thrown up”), can trigger a near panic attack.

I had thought that to face the future with anything but terror, I would have to become like Flynne (unlikely), or like Molly (inconceivable), who is literally made to fight and survive in the Sprawl, an environmental morass stretching from Boston to Atlanta and mostly shielded from the sky by geodesic domes. Molly has had her body modified—with neural enhancements, retractable blades under her fingernails, and mirror lenses surgically set into her eye sockets—to enable her employment as a ruthless assassin; she paid for these modifications by working as a “meat puppet,” a prostitute whose “cut-out chip” blots out her consciousness of the work. Science fiction is full of hard-boiled heroines like Molly. Cayce, though, is anything but hard-boiled. Indeed, her sensitivity—at the same time that it makes her so vulnerable—is her strength, enabling her to make her way out of the Borgean labyrinth she finds herself in when she is hired to find the elusive creator of what is called “the footage.”

“The footage” is fragments of film periodically released in corners of the internet that have attracted a cultish, but ever-growing, following. Cayce herself is a “footagehead” and frequent poster to F:F:F, an online forum on which footageheads discuss the fragments, attempting to locate its settings and interpret its narrative, both of which remain elusive. It is not even known—or discernible—whether the fragments are parts of a work in progress or “something completed years ago, and meted out now, for some reason, in these snippets.” Cayce’s investigation, beginning in London, takes her to Tokyo, Moscow, and farther into Russia—and danger—and her internal clock never quite syncs with wherever she happens to be. Through it all, the ghostlike memory of her father accompanies her: advising her to “secure the perimeter” after there is a break-in at the London apartment where she is staying, guiding her away from apophenia and paranoia, and, at one crucial moment, telling her to scream.

The pacing of Pattern Recognition feels slower than that of other Gibson novels (such as The Peripheral, with its rapid cutting from one point of view to another), and its close third-person narrator remains close to Cayce’s grieving consciousness from beginning to end. The footage, described as dream-like and evoking loneliness, and even Cayce’s jet lag, described as a kind of spiritual deprivation in which “her mortal soul is leagues behind her, being reeled in on some ghostly umbilical down the vanished wake of the plane that brought her here,” both contribute to the melancholia of the novel, as do its occasional sidelong glances at memories of 9/11. Her sadness and loneliness are most acute when she reaches out by email to the person she thinks is the maker of the footage. “I’ve been out there, out here, seeking,” she writes, “Taking risks. Not sure exactly why. Scared. Turns out there are some very not-nice people, out here. Though I guess that was never news.”

Strange that a novel about the past is the one that best connects me to my sadness about the future. Reading Cayce’s story, however, I seem to regard it much as Wilf regards Flynne’s present: a past to be longed for. Immediately post-9/11, pre-Iraq invasion, pre-iPhone, and pre-social media—Cayce’s particular point in history in Pattern Recognition grows ever more poignant for me, especially on each reread, as that point in history recedes and we continue move forward, it seems, toward the jackpot.