From the Ghosts’ Point of View: A Brief History of Seven Killings

In a book that promises by its very title and opening lines that many characters will be expected to die, the author has to do some coaxing to convince readers that they can invest emotionally in the story. Marlon James achieves this in A Brief History of Seven Killings by breaking the sound barrier of the grave. Readers often don’t know whether a character is still alive or dead until after the character has already been talking for a while. That very open-endedness makes it possible to empathize with these characters even after the (more than) seven promised killings take place.

Marlon James is unafraid to confront death from the first page onward and then invite readers to care anyway. Clues to practically every death in the 686-page book appear in those first few pages: “fifty-six bullets,” “a burned cockroach,” a scream that “stops right at the gate of his teeth.” In sharing this, I’m giving away nothing that James himself doesn’t already give away. Reader, you’ve been warned. But, reader, don’t shy away. This is a story with heart.

From the moment the first narrator, Sir Arthur Jennings, announces in his opening lines that ghosts “never stop talking” and that “when you’re dead speech is nothing but tangents and detours,” readers cannot be certain they are listening to someone alive or dead. The readers figuratively take the role of the living who “sometimes hear” the dead speaking when they are half-awake or near death themselves.

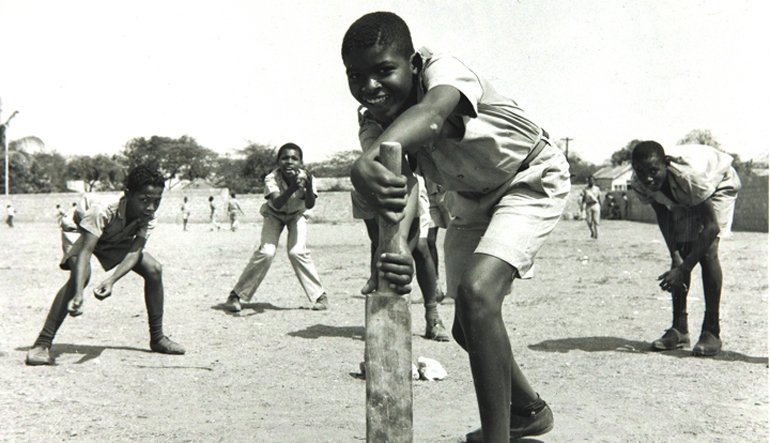

A certain openness of time and space reigns in this reimagined tale of the attempted assassination of Bob Marley on December 3, 1976, when he returned to Jamaica for a concert. That openness is generated by not only James’ choice of first-person point of view but also because the characters begin in medias res without necessarily explaining the backstory. Another source of openness is the figure of Bob Marley himself. Marley remains a creature of myth, not a fully-fledged character but someone who haunts the narrative in his own way—a strain of music, a line of lyrics, the silent and white-clad bodies of his followers, allusions here and there to his illness and impending death.

If anyone and everyone could be dead, then of course readers cannot avoid the operative question all curious people can’t help but ask: how did they die? A Brief History of Seven Killings enables empathy by ratcheting up the suspense, dragging out some answers to the very last pages. It is even intentionally misleading! More than seven people die, for instance, and yet some central characters end the book alive—some of them already marked for death, some not. That juggling act means readers are kept guessing about who will “make it” and who won’t. The titular reference to “seven killings” is itself a reference to an incomplete news article written by journalist Alex Pierce, who is later mocked for his wild inaccuracies.

And yet Alex got one thing right in his doomed article: the seven victims he profiled each suggested a glimpse into whole lives, voices talking in the dark. In the same way, the first-person narrators who people A Brief History of Seven Killings feel alive to readers in the complexities and contingencies of their “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” decision-making.

If suspense and curiosity allow readers to pick favorites, and root for them to make it at least as far as the book’s end, the quiet mercies scattered through the book also make space for empathy by allowing readers to hope for the “good death,” or at least the “better death.” One of my favorites got the worst of it, and yet I was relieved when his killers later got mercy. How did Marlon James make that possible? Two important choices: First, even killers long for something, love or intimacy or peace, and at key moments in the story, they got it. Second, death is exhausting, and after hundreds of pages of loud, desperate deaths, it came as a relief to witness one character dying in another’s arms and, finally, finally, to witness the composure of a (figurative) caged lion on the verge of death. That last image might not make as much sense as I hope to someone who hasn’t read the book, but trust me: even if you hate the lion, you’ll want to read his story, and you’ll come to respect him.

Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings manages, without oversentimentality, to give an honest accounting of death. From the ghosts’ point of view perhaps that is enough, especially where justice is too much to expect.