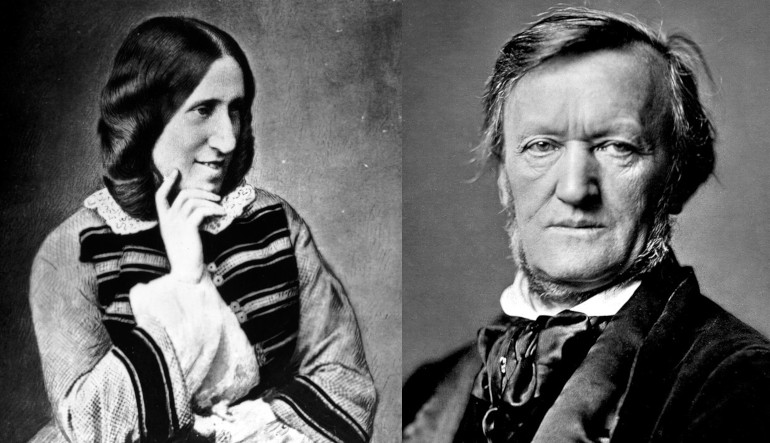

George Eliot and Wagnerian Opera

George Eliot had a great interest in music. Her partner, George Henry Lewes, was friends with the pianist and composer Franz Liszt and, through this connection, Eliot met many prominent figures in the European music scene of the late nineteenth-century, including Richard Wagner and his wife Cosima. To all appearances, this acquaintance seems to have been a happy one. In a letter to her friend Barbara Bodichon, dated May 18, 1877, Eliot writes “we are in love with Mad. Wagner!”, and Lewes later wrote to Cosima herself, professing that, “altogether the stirrings of the soul which the Meister’s music and your personality excited in us will make the May of 77 ever memorable to us.”

From her earliest encounters with Wagner as a musical theoretician and composer, however, Eliot engaged critically with his work. She praised his grand mythological themes, his use of leitmotif, and his vision for the future of opera, but admitted to finding his works overlong, and her own musical ear ill-tuned to finding pleasure in his music.

When Eliot and Lewes travelled to Weimar in 1854, they found themselves amongst the earliest audiences of three of Wagner’s operas: Lohengrin, Der Fliegende Holländer [The Flying Dutchman], and Tannhäuser. Through her subsequent 1855 essay, “Liszt, Wagner, and Weimar,” Eliot became one of the first advocates for Wagner’s music in England. In this essay, she displays a deep engagement with Wagner’s “music of the future on a theoretical level, and a simultaneous difficulty with the musical effect of these theories in practice.

Eliot rallied against her conservative preferences, mocking her own limitation to the “tadpole pleasures” of traditional melody, as her ear struggled to appreciate this new music. Yet, even in admitting that she was “unable to recognise Herr Wagner’s compositions as the ideal of the opera, and […] with a few slight exceptions, not deeply affected by his music on a first hearing,” Eliot affirms her support of some of Wagner’s key ideas:

It is difficult for me to understand how any one who finds deficiencies in the opera as it has existed hitherto, can give fair attention to Wagner’s theory, and his exemplification of it in his operas, without admitting that he has pointed out the directions in which the lyric drama must develop itself, if it is to be developed at all.

Despite this apparent contradiction between her theoretical and experiential reception of his works, Eliot does find some modest satisfaction in the experience of listening to Wagner. After discussing her issues with Lohengrin, she concedes that “Certainly his Fliegende Holländer […] is a charming opera.” And it is this opera which provides the model for Daniel Deronda (1876).

Eliot’s final novel—written between her trip to Weimar and Wagner’s subsequent trip to London, where Eliot and Lewes entertained him and his wife on several occasions—tells the story of Daniel, a young English gentleman with a secret Jewish heritage. Daniel remains connected to the fripperies and underlying hostilities of English society through his friendship with the proud and wilful Gwendolen Harleth, even as he simultaneously uncovers his Jewish roots through the humble Mirah Lapidoth, and her brother, Mordecai. These storylines are drawn together through one central commonality: opera. Opera figures most prominently in the narrative through the drawing room singing of both Gwendolen and Mirah, and the faded star of Daniel’s lost mother. It also subtly underpins the novel as a whole through Eliot’s use of Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman as a template for the dramatic and thematic elements of her work.

The story of The Flying Dutchman follows a sea captain, known as the Dutchman, cursed to roam the sea forever. His only hope of redemption is that every seven years he is allowed a brief return to land, where true love may break his curse. This pattern of absence and return plays out across Eliot’s novel between the two storylines, and the two separate worlds in which Daniel is involved. The figure of the Dutchman finds echoes in more than one of Eliot’s characters, and the themes of isolation and displacement he embodies provide the bedrock for Eliot’s discussions about a displaced Jewish culture, and the human condition more broadly. Like The Flying Dutchman, Daniel Deronda can be read—across several levels—as a novel concerned with endless cycles of isolation and the search for a home.

Eliot’s novel begins with the first meeting of Gwendolen and Daniel. It then progresses along two separate storylines—one following Daniel’s quest to uncover his Jewish heritage, and the other, Gwendolen’s struggles in English society with her restrictive and controlling husband, Grandcourt.

For Gwendolen, Daniel’s appearances in her storyline connect her with another possible life away from the control of her husband. Like the Dutchman’s periods of respite on the land, Gwendolen’s time with Daniel allows her glimpses of her lost freedom. The pattern of meetings as they are experienced by Gwendolen is reversed for Daniel. It is not his time with Gwendolen that offers respite, but the time he spends with both Mirah and Mordecai which frees him from the constraints of English society and reveals to him the cause that he has been searching for—namely, the Jewish cause. Eliot’s transplanting of the Dutchman’s characteristics across different characters suggests that the sense of isolation and the ongoing quest for a home that are so central to this figure are universal aspects of the human condition.

Daniel Deronda is centred on a series of dramatic and formal recurrences—a system of absenting and returning that structures the novel as a whole. These patterns of recurrence exist on a smaller scale in the form of recurring objects or images, echoing Wagner’s use of recurring musical themes, or leitmotifs, which are credited with lending cohesion to longer works. Foremost amongst the examples of leitmotif in Eliot’s novel is the dead face that Gwendolen sees—first behind the wainscot panel at Offendene that opens to reveal a “picture of an upturned dead face, from which an obscure figure seemed to be fleeing with outstretched arms.” This image offers a premonition of the death of her husband, following which, she is haunted by “a white dead face from which she was for ever trying to flee and for ever held back.” Like the “Dutchman theme” established by the French horns at the beginning of Wagner’s opera, this image of the dead face is tied to the character of Gwendolen and to her fate.

The scene of Grandcourt’s drowning towards the end of the novel invokes the high drama of opera, closely mirroring the final action of The Flying Dutchman. The end of Wagner’s opera sees the young girl, Senta, prove her love to the disbelieving Dutchman by exclaiming that she is “true till death” before throwing herself into the sea. Eliot’s inversion of this drama emphasises Gwendolen’s hesitation in saving Grandcourt when he falls from the boat. The contrast between these two scenarios throws each into greater relief. Gwendolen is Senta disillusioned by her time spent under the yolk of an unsuitable man. Blinded by the romance of an imagined life, Senta leaps from a position of unknowing innocence and naiveté, the same way Gwendolen first leaps into marriage. Yet, disillusioned by experience, Gwendolen does not move to help her drowning husband.

In reading Gwendolen’s fate, we may consider that Senta’s death in Wagner’s opera has saved her from the misfortune of an unsuitable marriage. Eliot’s subversion of the opera’s drama allows her to make a statement in response to the original work, which itself can be reinterpreted through this relation. As this shows, not all of Eliot’s invocations of Wagner are purely imitative—or assenting.

Further to the subversion of some of the dramatic elements of The Flying Dutchman, Eliot also confronts some of Wagner’s theoretical positions—in particular, his stance towards Jewish musicians. Eliot would have known, as early as the 1854 Weimar visit, of Wagner’s scandalous writings about Jewish composers. The issue of Wagner’s anti-Semitism was taken up by many contemporary critics, yet Eliot avoided discussing it in her essays and private writings. The stark philo-Semitism of Daniel Deronda can be viewed as her response. In a direct counter to Wagner’s views on the musical inadequacies of the Jewish people, Eliot invests her Jewish characters with a deep, almost mystical understanding of music that surpasses any of her English characters.

Eliot draws distinct moral lines between those characters who have a natural affinity for music, typically the Jewish characters, and those who do not. We see this in the description of Deronda’s voice, which, “heard now for the first time was to Grandcourt’s toneless drawl…as the deep notes of a violoncello to the broken discourse of poultry.” This contrast is further highlighted in the different approaches to musicianship shown by the Jewish Mirah and the English Gwendolen; Gwendolen views music as an instrument rather than as the goal itself and is criticised for “donning the life as a livery,” whereas Mirah, for whom music is a natural gift, pursues her art with humble determination and a willingness to work hard. While Eliot never openly condemns Wagner’s anti-Semitism, the treatment of the musical themes in Daniel Deronda offers a clear rebuke when read against his views.

Eliot’s interest in Wagner’s operatic principles furnished her final novel with a motivic structure in support of longer form work, and with the high drama and mythological underpinnings that made Wagnerian opera such a popular success. Viewing the novel as a response to Wagner, by turns appreciative and confrontational, allows for a deeper understanding of Eliot’s responses to Wagner’s music, and to his ideology, than can be found in her essays, letters, and journals.