Getting Here

I stood in a bookstore next to an author whom I would describe as both famous and wonderful, and she patted a stack of her own books that sat on a table, prominently displayed. She smiled a little—a private smile. She looked at me, a bit embarrassed that I’d seen her, and said, “It’s still weird to be here.” I told her I imagined so and that I looked forward to feeling weird, and I thought to tell her about Ploughshares and then thought better of it, and then thought better of that, and then I just blurted it out. Unfortunately, enough time had passed (we’d moved on to a different part of the store) that she jumped a bit when I said it. “I’m going to be in Ploughshares.” I told her it kind of made me feel weird, but the same kind of weird, I imagine, a very good, surreal weird.

***

In 1999, I attended the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. I was an undergraduate at Middlebury College, and getting my first real exposure to the life of a writer. I listened a lot, partially because very few people cared about what I had to say (and I didn’t—and don’t—blame them) but mostly because I knew I had a lot to learn, and one name that I heard again and again was Ploughshares. Soon after returning home, I purchased the Fall 1999 issue, edited by Charles Baxter. I still have it, of course, with a speeding ticket from that same fall tucked into the pages (I must have been in a hurry to return to school, though I don’t remember this ever being the case). At the time, I remember feeling a little frightened by Ploughshares; this was a kind of writing of which I’d only scraped the edges, even as a reader, and it seemed so vast and intimidating that I didn’t know what to do with it. And what was it exactly? Not a book. Not a magazine. But I read it, considered Stuart O’Nan and Antonya Nelson and all the others, and then read it again.

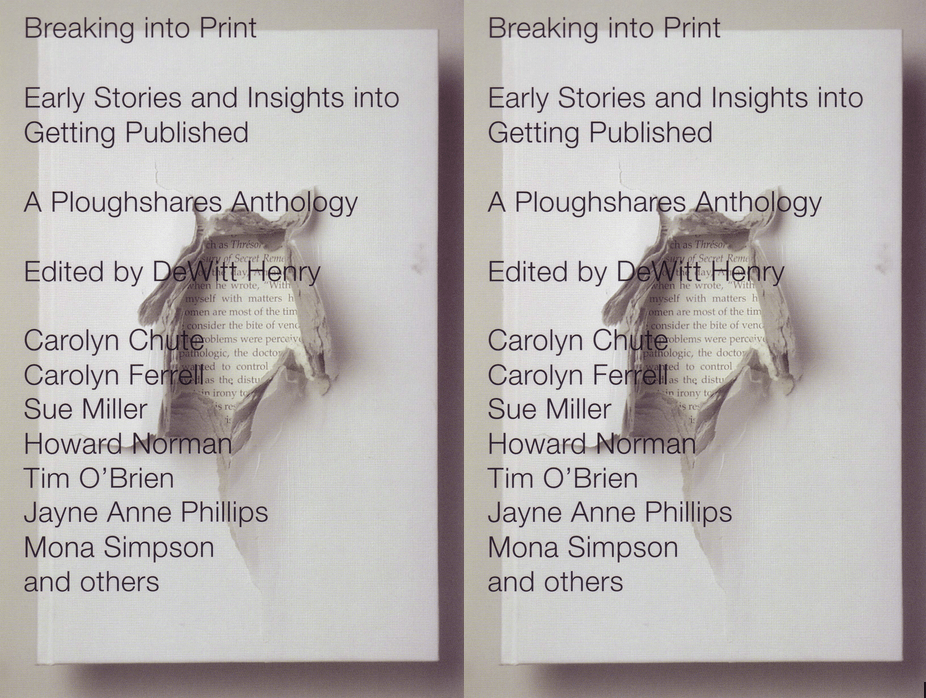

In 2000, I was working in a bookstore in Massachusetts, and I came across Breaking Into Print, DeWitt Henry’s loving anthology of writers whose early work appeared within the pages of Ploughshares. It helped that one of my heroes, Tim O’Brien, was included. The idea that Tim O’Brien had actually started somewhere had never really occurred to me. He had, I assumed, emerged in the world as a fully-fledged and amazing writer, with a dangerous muse who nonetheless drove him to spectacular heights. The idea that O’Brien drove himself to these heights was only slowly beginning to dawn on me; I’d bought into the idea of the writer as a conduit and not a laborer. Here, however, Henry encouraged me to think otherwise, that by laboring there is a magic that happens, and he displayed success after success.

Breaking Into Print forced me to try to make sense of the whole thing, and I began to understand, I think, what makes literary magazines special and critical. As Henry wrote in the introduction, “Ideally, the editor’s role is that of recognizing and cultivating promise.” This means being open to pushing the literary conversation, and to placing the work of veteran writers alongside newcomers, all under an umbrella whose only identifying feature is quality and the ineffable electricity of promise.

Reading Ploughshares was, and still is, like standing beneath a tree: every story is like a branch reaching out, and one can follow it to the work of the likes of Charles Baxter or Tim O’Brien. These works promise their future, a nearer future of where they are headed next in their careers; we see how they are shaping words right now. Other branches bring the farther-reaching promise of new names, which get stored away for a time when a book appears, and the story returns in fragments and shards. That was, and is, how I see it.

My writing progressed, and I saw it from the other angle as well. The Breaking Into Print angle. As Mr. Henry suggests with the title, publishing is increasingly fortified, a castle that must be stormed. He wrote, “While in the 1970s we often viewed ‘the establishment’ as repressive and indifferent to promise, Ploughshares and other literary magazines, largely funded by grants and volunteer zeal, helped writer after writer to attract attention from established agents, trade editors, and publishers.” Ploughshares is a battering ram. Of course, the magazine has its own moats and drawbridges. So, if it’s possible for it to be both a majestic castle unto itself and also some kind of castle-siege instrument, then it’s both.

Because Ploughshares is many things at once. It is a magazine. It is a book. This is its birthday, a hard-won and well-deserved milestone, and I am honored and thrilled to be a part of this anniversary. Especially with the company I find myself in, writers who mean so much to me. Howard Norman and Sue Miller are both featured in Breaking Into Print. Norman and Margot Livesey (my introducer, and the one person who truly introduced me to writing) were both on the faculty at Bread Loaf in 1999. Jane Hirshfield I only met last year at a residency, an accomplishment that also made me constantly tell myself, This is happening. To share this special issue with these writers, and especially Laura van den Berg, my editor and compatriot and—best of all—friend, fills me with pride. But it’s still a little weird to be here.

This is James’ first post as a Guest Blogger.