Going Home Again: Reassessing Little House in the Big Woods

The first book I ever loved as a child was Little House in the Big Woods. Part of this infatuation stemmed from how I received my original copy: I was the only kid in my third-grade class who hadn’t been given money for the book fair, so my teacher dug into her own wallet and bought something for me. That night I went home and read about Laura Ingalls and her family, how they worked together to provide for a tiny household lodged in the middle of a massive forest. The book featured wild animals. Butter churning. Fiddle playing. The Ingalls family enjoyed maple candy from tree sap thrown on fresh snow. They played with an inflated pig’s bladder, bounced around like a beach ball between two excited children. It reminded me so much of my own life—we had no money and were always trying to make the most of what we had. The Ingallses weren’t just struggling pioneers. They were my family. They were me. As a kid, I enjoyed what I saw mirrored back of my own life. Rereading now, I still enjoy uncovering those similarities.

I can see how reading Little House affected my writing and has also influenced what I find satisfying in books: through developing a strong sense of place and setting, finding different ways to tell stories, and by examining how interlocking domestic roles can impact the “survival” of a household. Little House in the Big Woods wasn’t just a pioneer narrative for me; it was an instruction manual, a way to look back and mark the shape of my own work. Rereading the book showed what I actually value in writing.

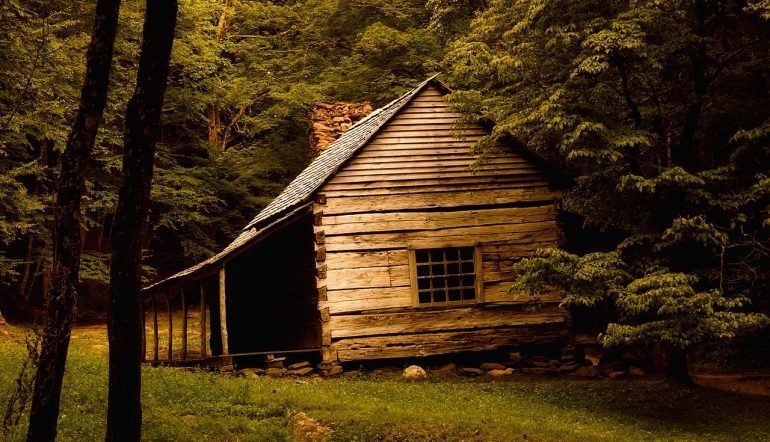

I often choose to read books where setting is valued as if it were a character, informing the work throughout. Little House opens with an immediate look at where the Ingallses live and how “place” shapes their daily lives. The family’s house becomes significant because of what surrounds it: a forest, which is both valuable and dangerous. The woods are what frame the narrative—particularly because aside from the family, that’s all there is:

The great, dark trees of the Big Woods stood all around the house, and beyond them were other trees and beyond them were more trees. As far as a man could go to the north in a day, or a week, or a whole month, there was nothing but woods. There were no houses. There were no roads. There were no people. There were only trees and the wild animals who had their homes among them.

There are trees and animals, there is the house, and there is the Ingalls family. The forest is not only what borders their lives, but what defines their survival: they depend on the woods for everything: their meat, their shelter, their crops. The seclusion and threats provided by the forest led to my focus, as a child, on the ways their home was described as cozy. The little house sat tucked inside dangerous woods, but its walls kept them safe from harm as long as they worked together to maintain their home it. The setting determines how their home functions, but it also allows them to live unencumbered by civilization. The woods frame how they access the world around them.

By describing the ways that a household can work, we also see the ways it can fail—the possibility of danger held up against the “safety” of home. Another way Little House demonstrates the importance of “safety” in one’s home is through the use of storytelling. The Ingallses’ Patriarch ventures out into the wild, dangerous world and comes home with tales of adventure for his family. These stories are peppered throughout the text as standalone chapters. “The Story of Pa and the Bear in the Way” and “The Story of Pa and the Voice in the Woods” are embedded tales that work to teach moral/safety lessons to Mary and Laura as well as to readers. Whatever Pa brings back to the household is ultimately digested by the rest of the Ingalls family; food and morality-tales alike. As a reader, I enjoy finding these types of inset-stories hidden in the work, discovering them like Easter eggs. I want to see ways in which telling stories builds a shared family history. I want to find safety in those narratives.

For the Ingalls family, every person in the household contributes to their continued survival. As a young reader, I found all the characters equally fascinating because none could not exist alone. There is loveliness in their continued dependence on each other and their landscape for survival:

In the yard in front of the house were two beautiful big oak trees. Every morning as soon as she was awake Laura ran to look out of the window, and one morning she saw in each of the big trees a dead deer hanging from a branch.

Beauty in survival domestic often means sustenance. As a young reader, Little House allowed access to the grimy, messy, violent parts of life—the idea that food comes from a living thing, that continued survival often means getting your hands dirty. Though Laura and her sister didn’t hunt, they helped preserve what was taken from those animals so the family could be fed. They took on lessons of survival as well as stories that frame their narrative. The domestic and the landscape remain intertwined. This is what I find myself returning to, again and again: the idea that safety in families is not guaranteed, that preservation of a household means looking closely at how domestic roles function in a landscape when someone doesn’t “perform” within expected social parameters.

As an adult, I recognize that many of the elements I found exciting in Little House had to do with how I was raised, but my enjoyment also had to do with what I value in work I read today. I still gravitate toward writing that tells me about place, that firmly entrenches me in a landscape. I want to know how a family works within the boundaries of a home to better understand each other. I also want to see how differences in a person can separate them from the narrative; how being too different can make a character unsustainable in a domicile. When I look at work, I’m seeking the joy I found as a very young, impressionable reader. I want the memory of what it meant to cure a deer with Pa and Laura, the nonsense of a pig bladder filled with air and tied off with string. I want the ugly delight, death, and survival. I want home to mean something.