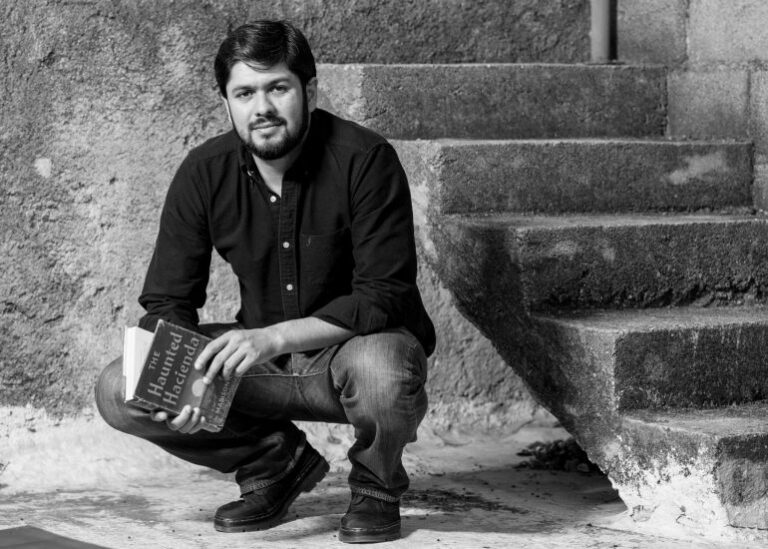

“Grief with animals isn’t the same, and we can learn something from that”: An Interview with Annie Hartnett

Anyone who knows me knows that I’m obsessed with animals, especially my deeply attached Australian shepherd, Zoë. Annie Hartnett shares a similar attachment to her border collies—first Harvey and now Willie—as does the animal-obsessed Elvis, protagonist of Hartnett’s debut novel, Rabbit Cake (2017), with her beloved border collie, Boomer, who helps Elvis navigate her mother’s death and changing family dynamics. When I heard the title of Hartnett’s second book—Unlikely Animals, out tomorrow—I was, of course, elated. While her enthusiasm for animals comes through, the novel is largely driven by family and relationships, though it’s clear that the characters could not get by—or survive, in one case—without their furry companions.

The book begins with the prodigal daughter’s return: Emma Starling has been off at college, then med school—or so she’s led her parents to believe—in California, and on her drive home to her small town of Everton, to which she’s returning in order to spend time with her dying father, she picks up a Great Pyrenees mix on the side of the road. She names him Moses. Emma’s return is awkward—so much has happened in her absence. Her former best friend has disappeared and the search for her has been abandoned by all except Emma’s father, Clive, since the police and townsfolk think Crystal overdosed on heroin. Emma’s mother, Ingrid, has allowed Clive to return home after his infidelity. Clive’s degenerative brain disease has begun to cause hallucinations (of animals!). And Emma’s brother, Auggie, is still struggling to bounce back after his second stint in rehab. Upon her arrival, Emma struggles to explain to her family why she didn’t, in fact, go to med school; why she got fired from her job at a retirement home; and that she’s lost “the Charm”—her ability to speed up “the natural healing process,” which she tried to use on a patient at the retirement home, to bad effect. With it gone, she has no chance of healing her father as her family had hoped.

In short order, however, Emma is appointed her father’s guardian and becomes a fifth grade class’s substitute after their teacher has a breakdown following her husband’s arrest on drug trafficking charges. With Ingrid, Auggie, and Emma out of the house during the day, Moses becomes Clive’s guardian, keeping him company alongside the ghost of Ernest Harold Baynes, who served as a primary source of inspiration for the novel. Hartnett discovered Baynes when she came across “nineteenth century robber baron” Austin Corbin’s mansion and secret hunting park in Newport, New Hampshire, where Baynes served as the park’s naturalist. Hartnett includes photos in the book from Baynes’s life with his wife, Louise—and their animals—as well as excerpts from his writing.

As Hartnett will be the first to admit, there’s a lot going on in Unlikely Animals, but the novel’s narrators, the residents of the Maple Street cemetery, effectively unite all the threads. The cemetery residents date back through the centuries and range in age and cause of death, the most recent being overdose or drug-related accidents. Everyone eagerly keeps up with the present goings-on (including current affairs and technology), and the way they interact with each other—bickering and interjecting, reminiscing and judging—is laugh-out-loud funny. Yet this humor, Hartnett’s hallmark, never feels inappropriate. She uses it to avoid the devastation of so many sadnesses, making them manageable. Endearingly, the narrators can hear everyone’s thoughts, including animals. When Emma picks up Moses, they hear him “wondering if Emma could please crack [the window] a little to let some smells in,” then “Friend.” “We spend most of our time focused on the thoughts of the human beings of our town,” they say, “but sometimes it’s good to be absorbed in the thoughts of a dog.” The residents feel a wide range of emotions, and they especially love telling a good story. “One thing we’ve learned from one another, chattering away as we do, is that a good story doesn’t always follow an arrow, sometimes it meanders a little instead,” they say. Unlikely Animals’ story has dark parts and sad parts, but its ghosts entertain without irreverence, giving their audience something to laugh about too.

By combining the voices of the dead with the experiences of the living, Hartnett also builds a sense of community. At one point, Clive is found walking in town with his pants off, a result of the brain disease. After Emma returns him home, Clive tells the ghost of Harold Baynes, “‘That was only the imperfect human body having a hard time’…something his wife had said first, to Auggie,” while he was detoxing from heroin. Clive reflects that “that was exactly the kind of reassuring thing you say to someone you love when they are being an awful burden but you’re trying to convince them that you don’t mind. Not at all. No big deal. For you? Anything.” In many ways, this sentiment is at the core of the novel: individuals are not navigating hardships in isolation but with the support of family and friends, animals and the dead. Yet this lesson is hard earned—they must first learn how feeling like they’ve let themselves and others down is a hindrance to surviving hardships together.

I spoke with Hartnett about these themes—and animals—over Zoom. Her dog, Willie, was unable to join us due to a terrifying fly being in the room, but Zoë was by my feet the whole time.

Sarah Appleton Pine: Obviously, animals are my favorite, and I know you like animals, too, because of the book but also because of Rabbit Cake and your beloved dogs. I’m curious to hear more about how your love of animals made it into Unlikely Animals.

Annie Hartnett: When I started writing Unlikely Animals—or when I was trying to figure out what I was writing—I was worried about having another book with a lot of animals in it. My agent and my editor at Tin House both said they didn’t think anybody who has read Rabbit Cake would expect me not to have animals in my next book. It’s just too much of my main interest. I guess I sometimes need permission to pursue what I was probably going to pursue anyway and not feel self-conscious about it.

This book came to be because of my interest in animals. I was writing a book about fifth graders and their substitute teacher—that was where it started—so that didn’t really have animals in it. Then, when I was in New Hampshire, I found this mansion with a big secret hunting park behind it. I was so interested in this big mansion that looks so out of place in that part of New Hampshire. I Googled it and found out the hunting compound has been there for 130 years. It’s one of the reasons white-tailed deer came back in New England after being hunted out, beaver, too, and bison were shipped out to Yellowstone to help repopulate the wild population. When I found out about Ernest Harold Baynes, it was stuff that I just couldn’t not write about—it was too interesting to me. I think that’s sort of how I feel about writing: you are going to be happy writing about something if you follow your own obsessions.

SAP: There are such good animals in the book, like Moses—he’s such a good boy.

AH: In Unlikely Animals, I change the breed of dog from the dog that I have. In Rabbit Cake, the dog was a border collie, and that was very much my dog, but I think it would be intense to have a border collie in every book because they are just such intense dogs. Moses is much more like dogs I have known but have not had myself. I love Great Pyrenees dogs; I just think they are beautiful, but they’re more goofy, happy-go-lucky. Although Great Pyrenees are a little bit like border collies—they are herding dogs—so I think it was a happy medium.

SAP: Moses is an endearing pairing with Rasputin, the pet fox Clive orders from Russia—at the prompting of Ernest Harold Baynes, who had his own beloved pet fox. Moses and Rasputin are kind of like those big dog/little dog or interspecies friendship videos you see online all the time. They clearly have a relationship, especially when it comes to Clive. They’re a team, they’re like his primary caregivers, and Emma is Clive’s struggling legal guardian off to the side while the two animals are his constant companions.

AH: Yeah, they needed to have radically different personalities. What was actually strange about the animals and Rasputin is that Rasputin originally did not have—for a long time—a point-of-view, which I had so immediately given the dog. As soon as I had the cemetery point-of-view, which I also didn’t have for a long time, I was like, “Why wouldn’t they be able to hear what the dog is thinking?” I loved writing that stuff, but it wasn’t for a long time that they could hear what the fox is thinking. We’re always imagining what our dogs think but not necessarily what a fox thinks, so Rasputin’s point-of-view was one of the things that came last.

SAP: That surprises me that you didn’t start with the residents of Maple Street cemetery as the narrators and that this came much later. I really enjoyed them—they’re having fun, and they share the experience of this story and what it feels like even though they’re dead.

AH: They’re always in service of telling a good story—that’s one of their main goals—so they are not trying to spoil anything until it’s the right time to tell it. That’s something that I had to really walk a fine line of: what did they know and what didn’t they know. What was so fun about that was all the asides I could add. I like books, John Irving’s being some of them, where I’m like, “Why are we getting all this stuff?” But I trust that you’re going to do something with it. Or it makes me laugh or I’m not thinking about it, and then it shows up later like this great magic trick. I wanted to do something like that and having the ghosts [be] narrators makes that easier because they’re telling you everything. Since they’re telling this story after the fact, they’re telling you everything for a reason, so they can say things like, “Pay attention to Mavis Spooner because she’ll come back.”

SAP: Right away as a reader I liked learning about Mavis Spooner, who’s reclusive and lives alone in the hunting park, not necessarily because she reveals more about the place but because she’s a wacky old lady feeding the bears, like they’re just any ole stray animal. She tells Jack, one of the bears, “Don’t be huffy,” when he’s impatient for food, and she talks to him like he’s a human. The way the narrators include this detail is witty and entertaining, but they also say, “The lives of the living often get tangled up in unexpected ways, especially in a town as small as ours, even when an eight-foot electrified fence splits it up.” So we know this detail will matter later and that the boundaries will blur in some way between the town and the wealthy people secluded in the hunting park.

If the dead weren’t the narrators, your book would just seem really depressing and not nearly so funny, even though a lot of the funny things come from thoughts and interactions from people who are alive. I think it’s fascinating how you managed to make stuff like death, a degenerative brain disease, and the opioid crisis not themselves funny but manageable for the characters and not totally depressing to read about. There’s a lightness, but I never feel like there’s inappropriate irreverence.

AH: My main interest is to make people laugh. I wanted to have a lot of different events work together to lead up to something big and to have fun with it along the way. The ghosts allow for all of that stuff to not to be taken too seriously. They understand the value of life, too, like how much surviving even an extra couple weeks means. These narrators allow me have a lot of the lightness that I like to write from, and just be more playful with stuff that may otherwise be inappropriate since it’s from the dead who have a different perspective on things that we deal with in reality.

SAP: There’s this acknowledgement, too, that it’s okay to be sad, which Emma at first struggles with when her fifth graders are sad on their dead classmate’s birthday. When she asks them what they want to do to not be sad anymore, they “put their heads on the desks [and] said they didn’t need any cheering up, they needed to be sad.”

You said that you were concerned about this novel being animal-driven—which is kind of funny given the title—but even though there are some wonderful animals in the book, it doesn’t feel animal-driven. It feels relationship-driven. Everyone in the town knows each other, they’re all up in each other’s business all the time, they’re a small and close-knit community, but then there’s also some serious tension, especially around the opioid crisis, because some people have no empathy for those struggling with substance use disorder while other townspeople don’t give up on them.

You also show how people react when they let someone down. That’s kind of how Emma gets back home. She’s really worried about letting her dad down by not healing him, but in the end, she realizes that her dad knew all along she wasn’t going to be able to. All along the way, there are times when characters are working through letting themselves or, from their perspective, letting someone else down.

AH: I see the book in a similar way. Even though it’s called Unlikely Animals, it’s mostly a book about the family and that they are all going through something. They are broken in the beginning and need to work through these months of stuff that goes on, and they need to get out of that house for a while too. Ingrid needs a vacation—also she’s already grieving and doesn’t know how to deal with that she just doesn’t want Clive to die. So I do not blame Ingrid for any of her actions, although I know she’s probably the least sympathetic of the characters, but if she didn’t leave, I don’t think Auggie and Emma would have been able to heal the way that they do. Auggie has stuff to figure out with his sister, and Emma needs to see what she’s missed because she knew it got bad, but she didn’t really think about how bad it got because she wasn’t ready to think about it and because it was too painful to think about. So, yeah, it is a book about family, and then the animals, just like the kids, are supporting cast members. Clive, more than anybody for me, is the heart of the book.

SAP: Grief also seems really important. It’s always there. They’re all grieving, even the residents of Maple Street who are still very much concerned with the townspeople. How characters go through grief and how grief drives the book is really interesting.

AH: I had written a book about grief already—Rabbit Cake—so that was another thing that I was like, “I don’t want to do that again.” But I do think I wasn’t quite done with—and had not really answered or had not wrestled enough with—the question, “What happens when we die?”

I was depressed when I started writing Unlikely Animals. My dog had just died, Harvey, the “Velcro dog” who went everywhere with me, and I never left him. So when I started writing Unlikely Animals, I was super depressed and thinking about death all the time, and then my dad had a heart attack the year Rabbit Cake came out, so that was on my mind, too—my dad is still very much alive now, but I wasn’t done with figuring out what I think might happen after death. I went to go see a dog medium, and she said something pretty profound to me and helpful: animals don’t hold on to the past the same way that we do because animals live in the moment. That was sort of how I came around to this question I wanted to try to answer at some point: Why do I think that might be true? That if there’s some sort of afterlife, humans have a harder time letting go of the activities of the living and that animals might be much more free afterwards? Grief with animals isn’t the same, and we can learn something from that. That was the thing that really freed me from the absolute misery I was in when Harvey died. They live in the moment.