Handiwork and the Making of Motherhood

When my son was born, I became obsessed with making. It was as if his coming into the world flipped a switch somewhere inside of myself that compelled me to create things with my hands. This desire to make was not necessarily anything new—I come from a long line of makers on both sides of my family—but I had until then always been lackadaisical about my projects, only taking them on from time to time, usually with a lot of space in between. There was something about the arrival of my son that suddenly made this business of handwork feel extremely, viscerally important to my everyday life.

In Sara Baume’s 2020 book Handiwork, she, too, confronts the process of creating things with her hands. Like me, she is a writer, spending much of her day at the computer typing words onto a blank screen. But amongst her writing and the everyday clutter of life, she also makes space for projects that require her hands. “This house is a house of industry,” she writes. As she navigates her own relationship to the process of making, she reflects on the makers in her family, the importance of time, and the undeniable pull of generational tradition. Migrating birds appear and reappear throughout the text, reminding Baume and her readers that the habits of our familial past are never that far behind us.

On the couch in my house lies a blanket that my maternal grandmother knit for me when I was a young girl. She knit a blanket for each one of her children and her granddaughters. It took her many years to finish them. We all patiently waited in a figurative line until finally, it was our turn to receive this beautiful, warm thing that she had created with her hands. Now, when I wrap myself in my blanket at night, I think of her fingers knitting and purling over and over again, intent on creating something out of nothing for me. Each stitch holds a tiny piece of her in it, in that each stitch is a choice made directly by her at a single point in time that led to the creation of something specifically for me. The stitches symbolize a choice to continuously choose love. It is an object that I cherish with so much of my heart.

My mother is also a knitter. She learned it from her mother, and now it is a practice she returns to often. When I visit her at her house, there is always a knitting project in the midst of being completed. When my son was born, she knit him an uncountable number of hats in all different sizes and colors so that he has never been without warmth on the top of his head. She has knit him mittens and leg warmers and one beautiful, cream-colored shawl. Throughout his first winter in this world, he has been a boy enveloped in knits. But it’s not just my mother’s knits that have kept the cold away from his tiny fingers and toes. He has also been gifted all manner of blankets and quilts from family and friends that pepper our couches and our chairs, available to him whenever he may need a little bit of extra warmth.

When I talk to my father about knitting, he tells me that my Oma was an exceptional knitter. “She knit like a bullet,” he says, and I believe him, though I don’t think I ever got to see her in action. But it’s clear to me that knitting is in my blood. So many of the mothers in my life have gravitated to it throughout their lives, and so when I made the decision earlier this year to finally learn how to knit for myself, casting on to a pair of knitting needles for the first time felt like returning home. Sure, there was a bit of a learning curve, but my fingers quickly learned how to make sense of the complex bundle of sticks and string that I held in my hands, and now I too find myself amidst multiple knitting projects—blankets for babies, including my own, and a Pinterest folder of future knits I hope to get to sooner rather than later. Baume talks about the migratory patterns of birds and the sheer unbelievability of their knack to just know where to go. She describes the wheatear’s migration as “the convoluted, inefficient, superfluous directions that are her genetic inheritance.” Perhaps my genetic inheritance is reflected in my ability to know when to yarn over, to know when it’s time to cast off.

When A was born, it felt like all of time compressed on top of itself. In those initial days after bringing him home from the hospital, everything felt both infinite and lightning quick. I began to become anxious at the passing of the days, where it seemed like every morning my son was a little bit bigger, a little bit different than the day before. Everything felt like it was slipping through my fingers—my son’s infancy, my own life—and I became desperate to try to capture as much of the present moment as I possibly could.

In the beginning, this meant an infatuation with photographs. I told my mother that I wanted to finally work through the dozens of boxes of photos from my childhood and organize them into albums. I began sifting through the thousands of images on my phone, sending jpegs off to get printed into hard copies that I placed into scrapbooks, one for each year. There was this desire to make my memories tactile both for myself, but also so that my son might be able to look back at his mother’s days and find something there that interested him. But soon the photographs weren’t enough, and I began to think of all the things I would like to fill his life with, which in turn were also things that I hoped to fill my life with. And so, I began to make in earnest.

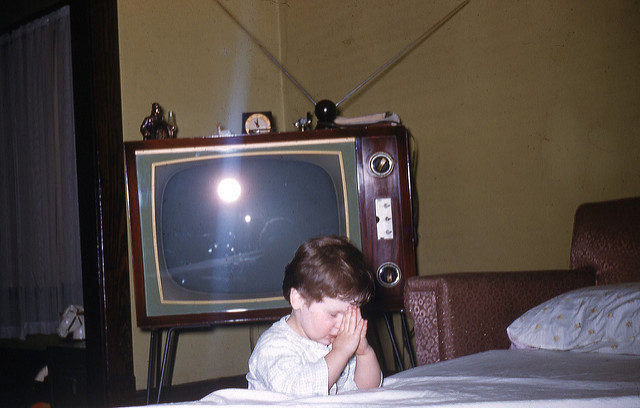

The first thing I made for A was a giant papier mâché moon. It had been decades since the last time I papier mâchéd, but suddenly I felt compelled to do this for him in time for Halloween. At night, after he had gone to sleep, I sat at our kitchen table and layered paper onto a moon-shaped wire frame. I did this for days, alternating between layering paper and letting it dry until eventually the crescent moon made a delightful hollow noise when I tapped on it with the tips of my fingers. Then, I carefully painted it a bright shade of yellow, giving it an honest looking face and finishing the whole thing off with small patches of gold leaf that shimmer when the light hits it just right. The first time A saw it, he smiled wide, and I felt as if, for the first time on this new mothering journey, I had done something right.

Soon after the moon, the Christmas season began, and I took to it with an intensity like never before. I learned how to make beeswax taper candles and spent an evening in the kitchen, dipping and re-dipping wicks into a double boiler late into the night. I made photo albums of A’s first year for every member of the family, perseverating over which images to include and which to leave out. Throughout the entire months of November and December, I worked on hand sewing Christmas stockings for A, myself, and my husband, each one embroidered with our name and adorned with a sleigh bell and ornament. The fabric I used was carefully selected from the stash I had inherited from my grandmother after she died. When I pressed it with a hot iron to make it ready to sew, the steam released the long dormant smell of her basement that sent me reeling at my kitchen table in the late afternoon sun.

At first, I couldn’t tell you why I felt compelled to make so many things so quickly. I just knew that I needed to do it. But now, as I sit and reflect on all the time I have poured into the act of making, what I have really been trying to do is assert myself to the world. I think, delirious on new motherhood, throwing myself into the act of creation helped anchor me to something concrete so that I might not feel so detached from myself and my own body. Of course, I also thought about my son growing up surrounded by things made by the people in his life. I want him to live in houses where warmth and history can be felt from the objects that he finds there. But my process of making is also, selfishly, about myself as well. When I look at my son, I am constantly reminded of my own impermanence, that mine and my husband’s generational line continues through him, and that we are no longer as young as before. Making, then, has also become a way to combat the passing of time, as if by creating I can come to terms with my own eventual death.

But of course, even though the birth of my son sparked something in me to push myself to make more and more, I cannot forget, as cheesy as it sounds, the greatest act of making I have ever known, which is him. For 10 months my body knew just what it needed to do to create this tiny person, and now he is here, and he needs to be cared for and loved. I often think about how every day he is learning from me simply by watching how I interact with the world, and so my impulse to make constantly is also my way of showing him that life is always about continual handiwork. The most beautiful thing about it is that it is something we return to over and over. There is mundanity to it, but also the beauty of keeping a practice. The beauty of knitting the same stitch again and again until, eventually, a blanket.

Is there anything more precious or more full of life? I think Baume would agree with me that there is not. “Every morning, I place everything out in preparation for the day,” she writes. “Every night, I tidy up, and place everything away in preparation for the next day.” We surround ourselves with these miniscule acts of living that add up to a whole existence. I want my son to understand this. To understand that grandness doesn’t have to come by way of large gestures. That a single, repeated stitch or a well dipped candle can be enough to create something magical. That all of this, this making, is as Baume says, “the glorious, crushing, ridiculous repetition of life.”