How False Is Your Reality?

Not long ago, I attended a reading in Chicago that featured a talented Brooklyn-based novelist and a long-time friend of hers who had recently published a memoir. During the Q & A session that followed their reading, an attendee asked the memoirist if she had ever considered writing fiction. The memoirist’s reply was one that I had heard before, but it still had the power to rile me up. “I’ve thought about it,” said the memoirist, “but I’m interested in reality, so I don’t know…”

She’s interested in reality. Good. So am I. Most of the time, in any case. As a writer of literary fiction, and a graduate of an MFA program where I was a poetry student, I’d like to believe that any genre allows equal time for the real and the fanciful. Frankly, I wouldn’t want to read a memoir written by someone who lacks the narrative skills of a fiction writer or the ability to characterize the people featured in the memoir with a novelist’s devouring eye. After those predictable, rather self-congratulatory words had left the memoirist’s mouth, I also thought about how most fiction writers would likely say that what they’re writing is reality. If you are a true lover of literature, you probably read several literary genres with similar interest and enthusiasm. If you’re a writer, you do, I hope, regard every genre with respect, and possibly wish that you could master them all. When I read The Liar’s Club, for example, I was awed by Mary Karr’s lyrical language as well as her memoir’s novelistic qualities. Here was a poet who could write stunning prose. I can’t imagine Karr having answered the question above the same way the memoirist had: “I’m interested in poetry, so why bother with prose?”

Admittedly, I read more prose than poetry now, and more fiction than nonfiction, but I am attached to each of these genres and probably learn as much from one as the other. I also know that my earliest days as a student writer of poetry helped me to become a better writer of fiction. There’s a reason why most MFA programs require students to take workshops in more than their genre of concentration – knowing the challenges of another genre helps fiction writers, for example, appreciate what playwrights and poets and essayists do. If you’re writing in the same language, you’re working with the same basic toolbox. How do you write a compelling line of dialogue or an affecting line of poetry? How do you create a fresh, striking image? How does your eye interpret the way two people across the room are staring at each other? We’re all looking at the same world, whether we want to or not.

To return to the original violent bee in my bonnet, I really don’t get it when smart people say that they don’t read fiction because they don’t want to read stories that someone has made up.

…?

Where do these stories come from anyway? A galaxy, far, far away? The last time I checked, the stories we read come from Earth central, Milky Way galaxy, and the course we’re all enrolled in is Human Experience 101. If the reading attendee had asked the memoirist if she had ever considered writing science-fiction, and she had offered her interested-in-reality response, all right, I’d let that one slide. Nonetheless, I’d have to say that many readers feel more engaged and alive when they’re immersed in a novel, whether it is realist fiction, fantasy, or science-fiction, than in their own lives. Isn’t that what good books do, after all? Take us to the very near galaxy of a good writer’s imagination? Proust said, “There are perhaps no days of our childhood that we lived as fully as those spent with a beloved book.” Whether it was The Witch of Blackbird Pond or The Bridge to Terabithia or Old Yeller, we were seeing our own tiny slice of the world filtered through the perspective of a talented writer. We became the characters we admired; we experienced their heartbreak and wonder and friendships no less fully than they did.

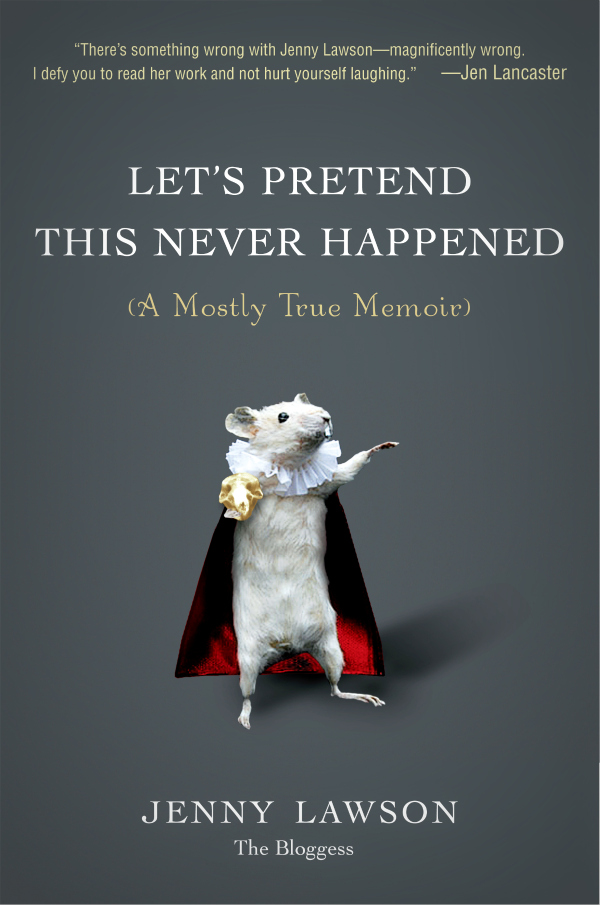

Another writer who was recently excerpted in a certain online journal that sends emails to its listserv every twenty-five seconds, wrote, “I’m not interested in writing fiction anymore. What a thing for a fiction writer to confess…Lately, I don’t even want to read it. What interests me is truth. Or someone’s version of it.” I have to wonder if there isn’t as much truth in a novel or a short story as in a memoir. Sometimes, I suspect there’s more. There’s also the fact that a memoir is an inward-gazing work, even if the best ones manage to connect, with eloquence and sympathy, the writer to the world he or she inhabits. Fiction’s gaze is more outward, even if the story might be semi-autobiographical. In good fiction, there’s often a prevailing sense of an author attempting to understand, and possibly celebrate, a mindset quite foreign to his or her own. Fiction allows us to imagine other people’s emotional lives in a way that nonfiction usually doesn’t. In its best incarnations, fiction is a bridge that links very different people living in very different places and eras.

I’m not saying that we should all aspire to write in every genre, but I don’t like the excuse that reality is more interesting than fiction, which implies that fiction is a far cry from what happens in the world on any given day. That’s a lazy and unimaginative perspective, two qualities no writer can afford to embrace.

This is Christine’s fifth post for Get Behind the Plough.