Imagination and Repetition in Chronic Illness Memoir

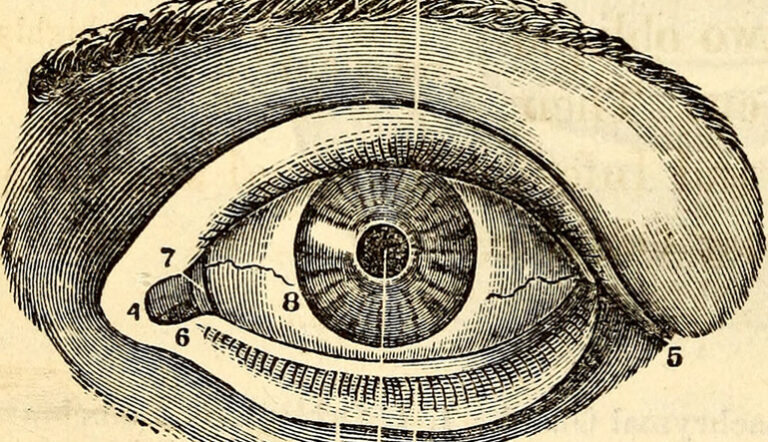

Certain encounters in my gastroenterology clinic call to mind Steven Millhauser’s short story “In the Reign of Harad IV,” first published in the New Yorker in 2006. Its main character is the Master, an artist who works in a royal court and specializes in miniature sculptures. In tandem with the Master’s increasing ambition and skill, his sculptures become progressively smaller in size—a ring of elephants carved from a cherry pit, a whole palace contained in a thimble—such that his fellow courtiers strain harder and harder to see them. Along the way, doubt slowly begins to color their appreciation of the Master’s work. His final project is one of tragic ambition, in which only the artist can see his creations, “deep-sunk in his invisible kingdom.” At this infinitesimal scale, it’s unclear whether his sculptures actually reside in the physical world or represent a figment of the Master’s imagination.

I don’t mean to suggest that I interpret my patients’ stories as fiction—I’m just struck by the additional hardship borne by those unable to prove their suffering to the people around them. Debilitating abdominal symptoms can shift and smolder for years, all the while resisting clear definition by biopsies or blood work. Uncorroborated experiences, like the Master’s audience wondering whether his hands are manipulating anything but air, make for a lonely existence. This loneliness can spark a special need for testimony, to assert how profoundly one’s physical experience has been disrupted, no matter how intact one’s body might appear to be.

In her recent memoir, The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness, out last month, poet and editor Meghan O’Rourke joins a growing collection of authors writing from the perspective of living with an unexplained chronic illness. Millhauser’s story isn’t mentioned in O’Rourke’s thorough bibliography, so I assume the resonance between the memoir’s title and the Master’s handiwork is unintended. Through an epigraph, O’Rourke points instead to the famous opening paragraph of Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor (1978): “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick.” This passage has served as a touchstone for several writers on illness; coincidentally, O’Rourke’s book made the New York Times bestseller list in hardcover the same week journalist Suleika Jaouad’s cancer memoir, Between Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of a Life Interrupted (2021), debuted there in paperback.

If Sontag frames illness as a kind of border crossing, O’Rourke aims to qualify chronic illness as a realm whose borders are obvious only to those who have crossed them. Invisibility is its own injustice, and she shares her personal narrative in the service of recognizing chronic illness as a collective problem. “I hope to offer context for why these syndromes have been hard to diagnose and treat and how they challenge existing frameworks,” she writes in the book’s introduction, “in the hope that it will help us revolutionize care and attitudes toward patients whose experiences have long been stigmatized.” Reception of The Invisible Kingdom has been quite positive, centralizing its value as a critique of our broken healthcare system.

While such critiques are important, they’re no longer revolutionary. Similar stories of marginalized illness have been published in recent years—like Porochista Khakpour’s Sick: A Memoir (2018) and Ross Douthat’s The Deep Places: A Memoir of Illness and Discovery (2021)—as well as shared in other formats—take, for example, Jennifer Brea’s documentary Unrest (2017) and Allison Behringer’s podcast Bodies (2018-present). And less formal accounts of chronic debility overlaid with medical disenfranchisement proliferate in real-time on social media platforms, organized by hashtags like #NEISvoid (shorthand for calls for help that go unanswered and proceed with “no end in sight”). This wealth of first-person narratives establishes strong precedent for criticism of mainstream medicine’s refusal to take chronic illness seriously.

Recognizing the strain of activism that drives these projects complicates the work of critically analyzing them, especially for clinical readers like me, guilty as I am by association with biomedical hegemony. When calling attention to their own invisibility in the face of institutional power, patients benefit from doing so in unison. And yet assessments of literary merit are often reflexively aligned with expectations of originality. As the genre of chronic illness memoirs expands, I find myself seeking out the new ground that each additional volume covers. It’s a problematic expectation for multiple reasons. Basic clinical propriety suggests that every illness, however singular or boring, should be met with equal attention. Sick writers often work harder than their well counterparts to string the same number of words together. And live debates over biomedical truth further confound the desire for originality within chronic illness narratives that are subordinated precisely because they deviate from the usual templates.

The subtitle of O’Rourke’s book, Reimagining Chronic Illness, seems to foreground these tensions. As a professional writer, O’Rourke stays aware of the contours of the story that she is telling, calling out its failures and frustrations along the way. She notes the inadequacy of available vocabulary to describe her physical experience: “I couldn’t find the words to make myself legible to others. (And I still have not found them. This text is full of silences and vagueness and lacunae: when I write ‘brain fog,’ I imagine that your mind slides over the idea, unless you, too, have suffered from it.)” At the same time, certain passages distill the mystery of her experience with moving lyricism: “What I learned cannot be summarized or turned into a useful truism. It rather resembles a glint in the earth, a bit of mica on the rock that catches the sun just so…this may be illness’s reality, its weather, the way swaying underfoot is a quality of sea travel one only knows in full by stepping back, once more, on firm land.”

But the work of reimagining requires a frame of reference, which in O’Rourke’s case is the biomedical mainstream rather than her literary contemporaries. Above the level of the line, then, many elements of The Invisible Kingdom’s construction still read as familiar. There’s its clinical progression, with accumulating symptoms that eventually bury the narrator under their weight. There’s a catalog of visits with orthodox and alternative medical practitioners, whose skeptical dismissals and credulous invasions of the narrator’s body serve as foils for her isolation and desperation, respectively. There are digressions into the available science, with special enthusiasm for evolving frontiers like the gut microbiome, which haven’t been around long enough yet for that enthusiasm to be tempered by disappointment. And there’s the final petition for institutional overhaul, almost dreamy in its sweep: “We need a restorative whole-being approach that goes beyond what the current medical system typically offers the chronically ill patient,” O’Rourke writes; “we also need structural reform and a commitment to research.”

The detailed management of complex illness turns out to be trickier to reimagine than the language that conveys it. For example, O’Rourke favorably describes a multidisciplinary care model at New York City’s Mount Sinai Hospital for patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome, or long COVID. She dwells on a behavioral technique that approximates diaphragmatic breathing—an evidence-based, Eastern-inflected intervention previously applied to depression, anxiety, and refractory belching (for the treatment of this latter condition, I sometimes teach it to my own patients using a free app on my phone). This context isn’t meant to diminish the technique’s utility, but to suggest that not all chronic illness patients may view it as a substantive paradigm shift. Granted, the breathing technique is offered in conjunction with physical therapy and a clinical approach that O’Rourke obliquely labels “validating,” but prescriptions of graded exercise have been heavily criticized in adjacent chronic illness domains for some time, and good bedside manner is necessary but not sufficient. An approach that O’Rourke embraces could well be rejected by others as just the latest in a series of psychosomatic dismissals.

Here, perhaps, the kingdom splinters. From the private depths of individual suffering, standards vary for clinical solutions that are sufficiently more creative than their predecessors. O’Rourke seems to recognize the difficulty of addressing chronic illness patients in aggregate, peppering her language with qualifiers—“in a sense,” “may or may not”—to avoid alienating individual constituents of a population that already resides at the margins. Bold claims in chronic illness memoirs are usually circumscribed by personal experience, with the understanding that they need not apply to the chronic illness community at large. But the genre’s impulse toward collective advocacy is entrenched enough by now that it can be hard for authors to sidestep the presumption of writing on others’ behalf. As such, inventive thinking about chronic illness can also be risky.

In The Deep Places, for example, Douthat synthesizes the ongoing debate about potential causes of chronic Lyme disease before flouting the conventions of biomedicine altogether, citing his equivalent treatment responses to antibiotics, electromagnetic waves, and prayer, respectively: “I realized it had been some time since I’d directed any begging heavenward, and I thought to punctuate the last Ave with a plea for help…What followed was just as sudden and surprising as taking the Tindamax and the antibiotic together, or using the Rife machine for the first time. Once again it was like being a marionette whose strings were suddenly jerked, my head shaking, my jaw chewing air, my legs kicking, a frantic urge to rub my hands all over my torso.” Similarly, in Sick, Khakpour draws causal links between symptom activity and international headlines: “My Lyme relapses almost always coincide with global turmoil. It was no wonder to me that I would often become sick after some external political stressor, like the Paris attacks, or the election of Donald Trump.” These anecdotes are fascinating refutations of the modern, materialist model that governs conventional approaches to healthcare. They are also fodder for resentment from readers still trying to color within the lines of biomedicine, reluctant to venture out on these same precarious limbs.

Khakpour’s memoir toys with one of the more dangerous ideas imaginable to chronic illness advocates—namely, that the illness itself could be imagined. Like O’Rourke, Khakpour periodically steps outside her narrative to regard it as an aesthetic object, but while O’Rourke focuses on storytelling’s potential shortcomings, Khakpour attends to its seductions. When reflecting on when she might have been bitten by a tick, she writes of a particular moment in her past: “It’s almost too poetic, the narrative that Lyme had come to me then — perhaps the writer in me believes it did because so many loose ends of events would be neatly tied there amid the tangles of character and plot.” Later, she wonders whether her illness might be a self-perpetuating identity: “I am a sick girl. I know sickness. I live with it. In some ways, I keep myself sick.” Against the tide of disease legitimization, these flirtations with an outmoded psychosomatic paradigm are both highly original and deeply subversive. This subversiveness in turn demonstrates the extent to which a formerly heterodox position — the physical reality of chronic illness — has become its own kind of orthodoxy.

The aesthetic project of chronic illness memoir is inescapably tied to its political project. Within the wider genre, we might discern a politics of repetition. O’Rourke’s book cites the work of medical sociologist Arthur Frank, who in The Wounded Storyteller (1995) categorizes accounts of unexplained illness as “chaos stories.” They are unconstrained by the usual rhythms of clinical logic and thus stripped of its usual narrative satisfactions. There’s no dramatic thrill of conclusive diagnosis, no payoff of complete recovery. By documenting her health struggles alongside other writers with similar experiences, then, O’Rourke adds to the shared work of habituating us to these thwarted expectations. Normalizing chronic illness makes a convention of the unconventional. To the extent that familiarity is a precondition for empathy, a certain sort of banality might even be framed as aspirational.

Banality doesn’t really sell books, though. Any given chronic illness memoirist chooses not only how long they will spend depicting the kingdom of many versus the kingdom of one, but also how closely the two will align. While these kingdoms’ concordance tends to make for more effective activism, their discordance is often more interesting. In the clinic, I read “In the Reign of Harad IV” as an allegory for science and its limits, but of course it’s a story about art and its limits, too. The window of favorable reception is framed by mundanity on one side and legibility on the other. In the case of contemporary chronic illness narratives, that window’s relative narrowness makes it easy to feel crowded, even as each author works to open it a little wider.