Innovators in Lit #15: Richard Nash

Richard Nash is an independent publishing entrepreneur—VP of Community and Content of Small Demons, founder of Cursor, and Publisher of Red Lemonade. For most of the past decade, he ran the iconic indie Soft Skull Press for which he was awarded the Association of American Publishers’ Miriam Bass Award for Creativity in Independent Publishing in 2005. Books he edited and published landed on bestseller lists from the Boston Globe to the Singapore Straits-Times; on Best of the Year lists from The Guardian to the Toronto Globe & Mail to the Los Angeles Times; the last book he edited there, Lydia Millet’s Love in Infant Monkeys, was selected as a 2010 Pulitzer Prize finalist. Last year the Utne Reader named him one of Fifty Visionaries Changing Your World and Mashable.com picked him as the #1 Twitter User Changing the Shape of Publishing.

This conversation with Richard Nash will be the final interview in the “Innovators in Literature” series, and I can’t think of a better closing act. He is the epitome of an “innovator”—as his work with Soft Skull, Cursor, Red Lemonade, and now Small Demons demonstrates—and can always be counted on to show the rest of the publishing world what’s possible. Keep reading for Nash’s thoughts on Small Demons as the New Serendipity, Red Lemonade’s spring titles, and how we can better connect books to the larger world.

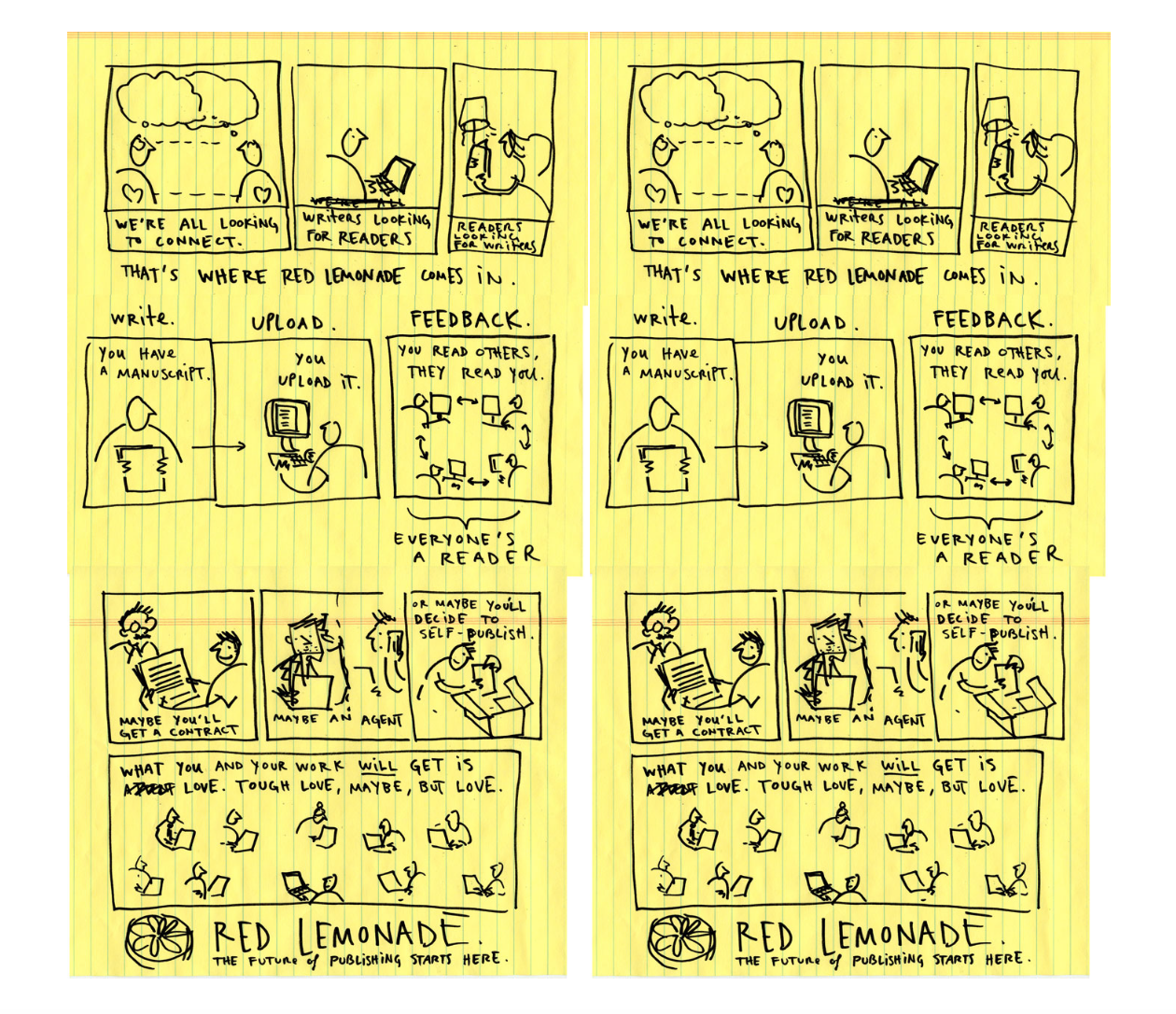

Laura: You recently launched Cursor, which is designed to “create a new platform (part web-app, part business process) for independent publishing, combining the best of editorial judgment and publicity moxie with community input into acquisition and promotion, and combining the tradition publisher/retailer process with digital publishing and limited editions.” For an industry that appears to be in a kind of limbo state—slowly recognizing the limits of old models but uncertain of how to proceed—the emergence of an entity like Cursor is super exciting. How did this idea develop? What was the impetus for not simply starting a press, but a multifaceted publishing company?

Richard Nash: Three big things drove the emergence of a whole generation of new independent publishers in the 1990s and 2000s. The first was desktop publishing, where the emergence of the PDF standard, software from Aldus, Adobe, and Macromedia, hardware from Apple, access to all the forgoing from Kinko’s caused the cost of creating a file a printer could use from $10,000 to $6/hour. The second, perversely, was the growth of superstore retail. Until this period, most bookstores carried five to ten thousand titles at most, a need that could be easily filled by the corporate publishers and a handful of independents. B&N and Borders superstores, however, carried 40,000-70,000 titles each, and there were a thousand of them. Then the third thing was the growth of distributors like PGW, Consortium, IPG, NBN, SCB and the distribution arms of Random House, Norton, Penguin etc., who helped all those presses using Quark and InDesign to efficiently get onto the shelves of the superstores.

I know that’s an very unromantic view of the rise of indie publishing, but given the culturally important role of these presses, it is critical to be clear-eyed about the economic basis of their existence. For it is not as if the system I outline above is one that provides a pathway to riches for indie presses. It simply took them from an impossible economic situation to a marginally possible one. And that system is now in decline. So I’m interested in understanding what infrastructure will support independent publishing for the next couple decades. Cursor is a model for that infrastructure.

Let me confess: we were unable to obtain appropriate funding for Cursor, so as a company it is in cryogenic suspension. But Red Lemonade, the prototype for a Cursor-modeled publisher, is as warm and lively as ever, so that is how I’ll continue to test and explore and refine the model in the coming years. Right now, the thing I’m doing that will be the broadest immediate impact is Small Demons, a project which creates a new serendipity of cultural discovery by identifying and connecting all the cultural references in books (music, movies, people, places, things), letting readers go where the story takes them. Driving cultural discovery, better connecting books to the larger world is a more urgent problem than building the long-term intermediary structures.

Laura: Cursor is the platform that powers Red Lemonade, a publisher that’s interested in “the writers other publishers are afraid of.” What kind of writing do you see other publishers shying away from?

RN: Writing that will sell fewer than 25,000 copies! Plain and simple. That means writing by people who do not have a large existing audience, or writing that does not lend itself to clear paths for orchestrating the purchase of 25,000 copies from retailers.

Laura: I really dug the first Red Lemonade book I picked up, Vanessa Veselka’s Zazen.

RN: The author reached out to me for advice, after I left Soft Skull. We had an almost year-long exchange around the best approach for her to publish the book. That exchange, which involved Vanessa serializing the book on the Arthur magazine website, discussions around her career, her background, her engagement with peers, with her audience, was, in effect, a microcosm for what I was trying to create with Red Lemonade. While the Red Lemonade M.O. is to select books from publication solely from those works that have been uploaded to our site by our members, I knew I had to pre-select three books that would provide some framework for writers to know what kind of writing community they were entering into.

Laura: I also appreciated the design of Zazen; it’s a great-looking book. Though technology is of course integral to the Cursor/Red Lemonade structure, there also seems to be an appreciation for the book as a physical object—was that always part of the Red Lemonade ethos?

RN: Well, the book as physical object is a manifestation of technology. Books tend to be offered as the antithesis of technology, but in fact they are its apotheosis. They are amongst the first objects humanity was capable of mass producing and certainly the first cultural/expressive artifact. We don’t think of them as technology because the book technology has been perfected over hundreds of years of weathering, sanded down to invisibility by friction with humanity. Books are like table, chairs, wheels. Technology we take for granted. I simply want to have the best possible human interface between culture and technology, be it analog or digital.

Laura: In an interview with TechCrunch, you argue that publishers “lost sight of their primary function: to help connect writers with readers.” This question of connecting readers with books has come up in other “Innovators in Lit” interviews, perhaps most notably in Christopher Newgent’s. How do you think publishers can best connect writers and readers?

RN: Foremost by accepting the primary function. I’m wary about taking the approach of listing four or eight or two activities that constitute writer-reader connection. In part because if you pay attention, we realize that many of the most avid readers of any press’s books are themselves writers. So I’m pretty dogmatic about avoiding prescriptive actions around, say, social media. “Should I use Facebook or Twitter?” is a meaningless question if you’re going to broadcast as opposed to converse, or if you’re going to converse but that conversation is performed just by the publicist. The entire publishing entity must be curious, porous, responsive.

Laura: In another piece with Interview Magazine, you talked about how “the model is going to shift from kind of a gatekeeper model to an advisor/service model. Or lets say from a bouncer model to a concierge model.” Could you talk about that idea a little more?

RN: Basically that was me saying we have to be in the writer-reader connection business. Just with extra metaphor! Curious, porous, responsive. Let me put it another way: we were always arbitrary as gatekeepers anyway, so we might as well accept that now. So as not to seem to be singling anyone out as a shitty gatekeeper, I’ll use myself as an example. I’ve been singled out, personally, for picking great books to publish, because people read the books and like them. But compared to what? Compared only to the choices other gatekeepers made. But to evaluate me as a gatekeeper, you have to look at what I rejected. Except few people have the slightest clue about all the books I rejected! When we look at the history of literature, it’s riddled with writers forced to self-publish, commercial failures, etc. Who knows how many masterpieces were never published, given how many masterpieces have come perilously close to not being published. We’ve been prisoners of the availability heuristic for a long time now, that’s the technical term for the phenomenon I’m describing. Instead of being in the masterpiece selection business, we should be simply participating in our culture, voicing our opinions with all the passion and rigor we can muster, but recognizing the contingency of the criteria we use to evaluate success. A publisher is a convening power for a discussion about what matters.

Laura: You’ve recently started working with a new start-up, Small Demons. How did you become involved with SD? What can you tell us about this project?

RN: Quite simply, when it became clear that investors were not going to fund Cursor, I needed to turn myself to something that was working right now. Luckily the founder of Small Demons, Valla Vakili, had reached out to me and some other publishing folk in the summer looking for feedback on what they were up to and I’d been offering advice and introductions. So I had the chance to see how transformative the Small Demons project was going to be. It is in live albeit invite-only mode right now, but invites are flowing pretty rapidly, so you can sign up and get your invite within 24 hours now. As to what the hell it is, exactly, well, I already characterized it here as the New Serendipity. What that means in practice is that we’re creating a vast database of all the cultural references within books to music, movies, people, places, events, landmarks, culturally resonant objects like guns, drinks, cars, Zippos lighters, Doc Martens. And we’re using that database to build a website (and, later, other apps and experiences) that allows a reader to wander through a vast networked gallery of our cultural heritage: clicking on the cover of Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity you see all the people, places and things it references, like Prince’s Little Red Corvette, the page for which, upon clicking its cover, reveals that the song appears in, inter alia, Haruki Marukami’s Kafka on the Shore, which itself references the Sony Walkman, which itself appears in fourteen of the first couple hundred books we’ve indexed, which might not seem like many, as it isn’t relative to what’ll eventually be there, but it’s enough to generated tens of thousands of connections to our global culture. Right now, most of the indexing is being done by computers with in-house human correction, but soon we’ll also allow our users to contribute, Wikipedia style, by correcting the computer’s mistakes and adding stuff computers can never know: for while they can tell use how many times a song appears in a book, they can’t know it’s the break-up song.

A couple years ago I proclaimed, in my usual grandiose way, that Tag is the new Shelf. Of course that was something that Clay Shirky has pointed out in 2005. By which I mean, wonderful as the bookstore is, the category is a pretty limited and at time tyrannical limitation, as a writer of a literary memoir about food will tell you, or as many African-American writers will tell you, or as a writer of speculative fiction will tell you, to name but three instances of a writer dangling between two choices as to where to be shelved in a bookstore. Whereas one book can have multiple tags. That’s as far as my imagination was capable of taking me. The genius of Small Demons is that it doesn’t just tag the book, it generates tags from everything is inside the book! So it’s driven not just by the categories a publisher or bookseller gives it, but all the references the author herself gives it. It’s writer-powered serendipity; it’s amazing.

Laura: Is there anything in the Red Lemonade/Cursor pipeline you’re especially jazzed about?

RN: Well, Red Lemonade has two books coming in the Spring: Matthew Battles’ The Sovereignties of Invention, a sublime story collection that I’ve taken to calling an exemplar of the hot new Dreampunk genre, and Rich Melo’s Happy Talk, a neo-pomo adventure that relates to Pynchon and Tom Robbins the way Mad Men relates to I Love Lucy. And then we’re helping the website HiLoBrow develop a book imprint, HiLoBooks, that will reissue in 2012 six early science fiction novels all published about one hundred years ago, classic of what the series co-editor Josh Glenn characterized in a series of essays on the SF website io9 as the Radium Age of science fiction.

Laura: What are some other publishers or literary entities you find inspiring?

RN: Oh goodness, they’re everywhere. I’m just going to throw a whole bunch of names at you and urge your readers to Google as many of them as they’re willing. Readmill, Findings, Featherproof, Two Dollar Radio, PressBooks, Librivox, Word, Libros Schmibros, Ugly Duckling, Triple Canopy, Melville House, Europa Editions.

Laura: What do you wish existed in publishing that hasn’t been invented yet?

RN: Honestly, I’m not looking for a deus ex machina. Everything we need we actually already have at our disposal. The danger publishing faces right now is in waiting. The tablet will save us, social reading will save us. No. There is no God coming. It’s just a question of creatively, humbly, ambitiously using the tools at our disposal right now.