Intimacy and Resistance Through Food

Leila S. Chudori’s 2012 novel, Home, translated from the Indonesian by John H. McGlynn in 2015, uses food as a mechanism to create and sustain intimacy during political exile and as a method of resistance against the imposed narrative of the dictatorship. Set mainly during the New Order government rule of Indonesia, the book, which spans a period of thirty years, begins in Jakarta just before the 1965 September 30 Movement, during which an organization of the Indonesian National Armed Forces killed six army generals in a coup d’état. The president at the time, Sukarno, and his government quickly blamed this on the Communist Party of Indonesia and began a genocidal massacre and imprisonment of communists, those suspected of relations with communists, and ethnic Chinese Indonesians.

Chudori opens her story with Dimas Suryo, a young journalist working in Jakarta during the end of Sukarno’s reign. As tensions between the government and its perceived threat of communism rise in Indonesia, Dimas leaves for a conference in Chile, beginning his lifelong political exile. While away, he and his friends hear about the September 30 Movement and find themselves cut off from their homeland due to their leftist political views. Dimas, Nugroho, Risjaf, and Tjai, unable to return to Indonesia without certain capture and execution, eventually move to Paris where they open the Tanah Air Restaurant, an Indonesian restaurant, bar, and event space that revolutionizes the city.

Dimas’s daughter with his French wife, Vivienne Deveraux, narrates the second, and most of the third, section of the book. A student at the Sorbonne finishing her final assignment, Lintang Suryo travels to Indonesia for the first time to make a documentary film of those victims of the government’s massacre following the September 30 Movement. A child of political exile, Lintang struggles with the concept of home and belonging, but through her intimate connection to Indonesian food, she quickly forms unbreakable relationships with her cousins and the children of her father’s friends, leading her to uncover the true aim of her documentary and her place in Indonesia and France.

Intimacy pulses through the novel—though the story takes place largely in a forced diaspora, Chudori’s luscious descriptions of food reveal the close bonds between people and place that survive political exile. Romance is almost always sparked by a discussion of food. Dimas’ first moment of relaxation in his initial conversations with Vivienne comes when he finally mentions luwak coffee, “that wonderfully tasting” Indonesian brew he sorely misses in Paris. During their marriage, Lintang recalls that many of her parents’ arguments, often over money, were resolved by food, too, such as in this common fight over what each deemed an appropriate breakfast:

No matter how hard she tried to maintain the scowl on her face, Maman would finally break into laughter and then join us in eating a plate of Ayah’s fried rice: hot and tasty to the tongue and rich from the oil he’d used to fry the rice. Ayah always liked to make his fried rice with minyak jelantah, oil which had already been used to fry something else, shallots and onions, for instance, so that their taste, too, was imparted in the rice.

After the two divorce, we see Vivienne drink luwak coffee alone, showing how food leaves an unforgettable impact on people even after they part ways.

In the early scenes of the novel, Dimas and his housemates’ elder friends, Nugroho and Hananto, use food as a guise to hide their romantic interests. They are smitten with Surti, Rukmini, and Ningsih, three young women who also hide their romantic wishes behind the pretense of coming to the young boys’ home to drop off cookies or food. As it would be improper to simply seek the company of the young women, the elder men slink into the kitchen where Dimas prepares a meal and “pretend to help by grinding chilies or preparing the seasoning by mixing shrimp paste with oil.” When Dimas’s housemate, Risjaf, finds out that Rukmini and Nugroho have become an item, Dimas mends Risjaf’s broken heart with his mother’s recipe for ikan pindang serani, an irresistible spicy and sour milkfish soup, as the “fish which had been simmered slowly in turmeric sauce never failed to cheer [Dimas] or [his] brother.” Ikan pindang serani reappears in multiple pivotal scenes of the novel, highlighting the significance of this emotionally charged recipe.

Food, in Home, is also linked closely to eroticism: in the early scene in which Dimas describes luwak coffee to Vivienne, he details its aphrodisiac qualities, claiming it is so delicious it can even cause premature ejaculation. Later on, Surti grinds chilies and spices in Dimas’s kitchen, the most important step in cooking for Dimas. He watches “the way she crushed the root—gently, wordlessly—she seemed to be coaxing the spices to surrender themselves to their individual destruction in order to create a more perfect union of taste.” Seeing a woman he finds attractive take on this process, held in such high regard in Dimas’s mind, makes him incredibly aroused. The catalyst of relationships, intimacy, and eroticism, Chudori’s food holds the untouchable power to evade societal restrictions related to gender, and ultimately, to connect people.

Food in the novel also reveals a mechanism for building trust, whether in personal relationships or political resistance. Dimas originally looks to writing to maintain his relationship with Indonesia in France. He and his friends, however, find themselves unable to affect France and the world around them through politics and literature the way they had in Indonesia. Dimas has the idea to turn instead to the culinary arts, and the four of them open the Tanah Air Restaurant, complete with a full bar and event space, which quickly becomes a pillar in the international community. While the restaurant as an institution holds immense influence over the community, it is the food Dimas cooks that holds the most clout. Again and again, Chudori reveals the transformative nature of Dimas’s food in dangerous encounters. It distracts the French police who come to interrogate the owners—when they see and smell the nasi kuning and sambal goreng udang “whose magic scent immediately suffused the air of the dining room,” their original mission dissipates and they focus only on the mouth-watering dishes moving past them, promising to come back to eat.

Similarly, Lintang brings three young Indonesian diplomats to the restaurant, despite the fact that all Indonesians working for the government are forbidden from associating with it because its owners are accused of being communists. While completely engrossed in their nasi padang, especially the beef rendang and the “chicken curry whose sauce nestled with the steaming hot rice,” they reveal to Dimas that they are a new generation of diplomats who form their own opinions on the political realities in Indonesia, and end up agreeing with Dimas on many of his views—a complete surprise coming from representatives of the Indonesian government that so strongly detests Dimas Suryo’s name, and a significant career risk for the young diplomats. At the restaurant, one of them even instructs Lintang on how to apply for a visa to visit Indonesia without getting stopped due to her family name. The Tanah Air Restaurant witnesses countless scenes of aggression and political tension, yet each time, Dimas’s cooking breaks down the hostile environment and replaces it with seeds of trust.

Lintang also benefits from this transformative power in the next generation. Though she is fluent in Indonesian and quite familiar with the country’s politics and history, food remains her main cultural connection. Once in Jakarta, she quickly realizes that she is an outsider despite her knowledge of history and the language. When student protests against the spiked fuel and goods costs erupt into the larger May 1998 uprisings, Lintang must come to terms with her status as a foreigner and her unfamiliarity with the chaos and danger of protests in Jakarta. She immediately defers to the friends she makes in Jakarta to keep her safe, and though they often do not explain any of their decisions to her for fear of being overheard by spies, she never questions their moves. Away from the protests, however, Lintang proves that she is just as much an insider with regard to food. Almost everyone she meets in Jakarta is impressed that she can eat with her hands, a skill she learned from her father that helps her fit in. When filming interviews for her documentary, it is through sharing a meal with Surti, her father’s former girlfriend, that she builds a relationship of trust strong enough for Surti to share her darkest tales of the time she and her children were tortured by the Indonesian government.

Connected at heart by the food that lives at the core of the novel, Home contains a fascinating oscillation between methods of recording history. The Tanah Air Restaurant provides an avenue for Dimas to preserve his culture as a political exile, but also functions as a form of resistance against Suharto’s New Order government, the authoritarian regime that comes about after the September 30 Movement. By creating a thriving hub of Indonesian culture after being forced out of Indonesia itself, the four founders of the Tanah Air Restaurant refuse to define Indonesia by its violent political figures and instead welcome other exiles, foreigners, and immigrants to find a home in Indonesian culture and food. While Dimas works in the Tanah Air Restaurant, he simultaneously records the stories of torture under the government his family and friends send him, compiling a manuscript of testimony against the New Order. Lintang discovers this manuscript along with all the letters that informed it, and decides to focus her documentary on their tales.

When she arrives in Indonesia, she discovers that the New Order government forces its own version of history on the Indonesian populace through dioramas “capable of disrupting childhood memories, inserting in them scenes of defilement, corruption, and horror.” The dioramas show reenactments of the September 30 Movement and parallel a filmed enactment with the same message. Both are shown year after year to Indonesian schoolchildren. These images twist the historical account in order to pin blame on communists and stifle any varying accounts. Though Lintang already knows many of the stories of the people she interviews in Indonesia because she has read the letters they penned to her father, when she sees the government’s use of image to dictate history, she discovers a new angle for her film. By documenting the tales of the victims of the September 30 Movement and subsequent massacre on video, she pushes their stories and histories into the same visual sphere that the Indonesian regime uses to erase it. Once in Indonesia, Lintang’s father’s form of resistance, culinary arts, becomes her main entry point to Indonesian culture, and there she brings the written, lived histories her father collected up to challenge the government’s enforced account.

Brimming with utterly delectable descriptions of Indonesian dishes from fried noodles to individually portioned and intricately compiled nasi uduk wrapped in bamboo leaves, Home displays the unique power of food to generate multiple forms of intimacy. Ranging from passionate romantic relationships to family ties, from the closeness that preserves cultural belonging when forced into exile to the bonds that are both built and broken in acts of resistance, the intimacy generated by food in Chudori’s novel impels the characters to take bold action in their personal and political realities, revealing the power in human connection and cultural memory that the New Order government cannot begin to crack.

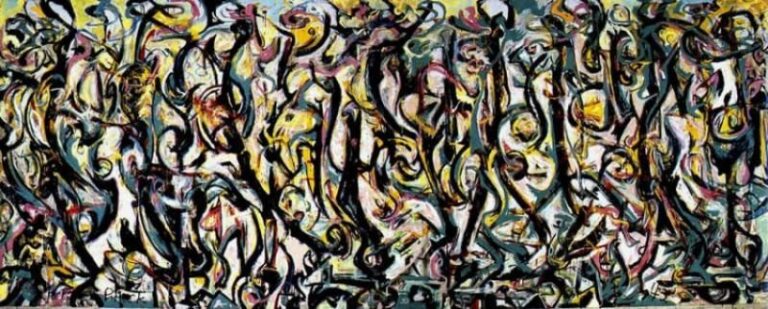

Image by Gunawan Kartapranata