Julie Maroh’s Body Music: Looking for Love in Montreal

You may know Julie Maroh’s work—she’s the author of the graphic novel Blue is the Warmest Color, later adapted for the big screen in a movie that continues to be divisive among the lesbian/queer community. Last year, she published another graphic novel, Body Music, a series of short vignettes about people and their love stories. It takes place in Montreal, starting July 1st—the day when people usually move out or in—and spans one year, coming back full circle.

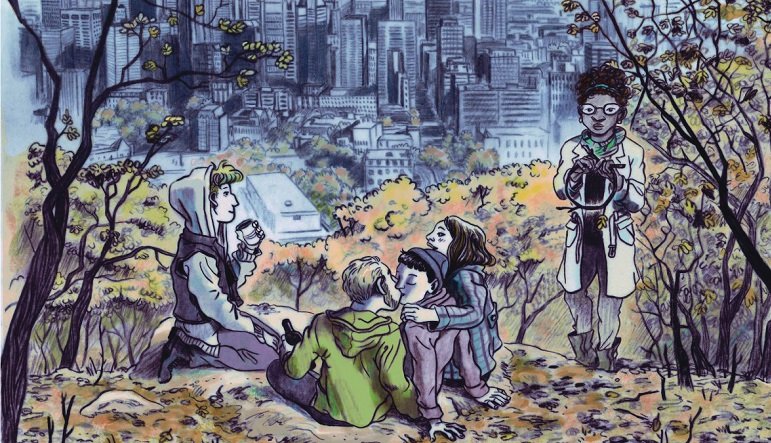

I said it’s about people and their love stories, but it would be more accurate to say that Body Music (or Sonorous Bodies, which is the literal translation from the original French) is about bodies navigating all the different routes of love, and about showing that most of these routes are queer, bucking up as they do against all kinds of norms. We witness the many different stages of love stories, whether these last one night or an entire lifetime, whether they involve one or more people. Characters come from many different ethnicities; many have various forms of physical disabilities. Gender identities aren’t confined to the strict binary. But the overtly political project of representation never feels like we’re going through a checklist, making sure everyone is “included” while leaving the bigger issues of the mechanisms of exclusion and discrimination unaddressed.

Maroh represents her characters first as physical beings—and the art itself bears the trace of this: it’s all about letting the individuality of each person shine through, maintaining a pared down yet robust style while having a knack for the significant details, for body language. This positions each character not as the stand-in of whichever group they would identify with, but as a body in motion through time and space. Body Music then isn’t a paean to “diversity”—that hollow word—but instead provides us with evidence of difference and community.

It’s also profoundly queer in the way the stories are told. While there are a few examples of vignettes working together to add layers to a story, or show the narrative from another character’s perspective, most of them are stand-alone. Their length means nothing is completely filled in: most of the world-building is left up to us. We catch glimpses into people’s lives that remain fundamentally open; while we may get a sense of resolution—conflicts are addressed, questions are answered—the outcome is always unknown since the conclusions each vignette comes to are provisional more often than not. A character declares their love to the couple with whom they’ve been having a three-way relationship; the couple responds in kind. How that committed polyamorous relationship will be negotiated, we don’t know. The vignettes thus exist in a kind of suspended state, embodied and irresolute at the same time.

But even though the stories are discrete, there’s a sense of a background overlap, invisible threads connecting the vignettes. They’re all happening in the same space, and if there’s one running theme throughout the collection, it’s that our attempts to reach out, to find community in all its forms, to counter heartbreak while not shying away from vulnerability, to navigate the slew of emotions that make us irremediably human—all of this provides cohesion.

This juxtaposition is also queer insofar as it completely disrupts our expectation of a straightforward, linear, moral-driven story. The lives depicted here in this postmodern framework are neither straightforward nor linear; their goal isn’t to impose or resolve everything into a moral. Not to mention that this is, quite literally, a hybrid work: the form of the graphic novel relies on both textual and visual aspects.

In this sense, it reminds me of Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, which serves as a hybrid space for the writer to delve back into her childhood, reflect on the evolution of her own identity through books and images using words and images, and understand how her own queer sexuality has opened up new forms of home and community for her. It doesn’t follow a linear chronology, and instead jumps back and forth in time, following the author’s train of thought as she appears to be piecing together different parts of her life in order to make sense of her relationship to her father. This is how the graphic novel memoir functions as a queer “home” itself, a free space that eludes genre categorization and where the writer can explore and reclaim for herself a fraught concept.

Even though Bechdel’s persona goes through a queer coming-of-age, and Maroh’s characters already feel settled within their queerness, the reflection on “home” seems to circle back to the same core ideas: that “home” for queerness is a complicated thing, that we are ceaselessly attempting to recreate new homes for ourselves. It’s no coincidence that Maroh chose July 1st as the date for the opening and closing stories of the collection: this is the date, in Montreal, when people move out and/or in, when change is very literally afoot. You move through space; you adjust to new surroundings, new conditions of life.

In recent decades, academia has started taking an interest in what are called “queer temporalities”: the idea that, since time is another social construct, queerness disrupts the ways we experience time. Body Music exemplifies this: here time is neither linear, nor wholly cyclical. The narratives loop back; but neither the characters nor the readers finish quite where they started. We get the urge of filling in the blanks in between the stories, crowding this Montreal with more characters of our own making. Ultimately, the graphic novel form helps us as readers participate even more in the creation and ramifications of the story. We’re like the mother in the second vignette, watching from her window two different persons in the park and imagining they’ll meet and fall in love, speculating on all the minute connections that would ultimately draw them to each other.

As Maroh writes in her introductory note, “there are as many love stories as there are imaginaries.” This may just be a reassertion of that old “write your own story!” cliché, but within the prism of queerness, it takes on a higher degree of significance and poignancy. What matters is that we see ourselves as bodies with the power to affirm our realities, far from the glossy images of ads and screens; that we keep recreating our own queer imaginaries, ceaselessly finding new forms and drawing new maps for them.