Katie Kitamura’s Explorations of Separation

Katie Kitamura’s most recent novels, A Separation (2017) and Intimacies (2021), are like mirror images: they share features, but with inversions. Both novels have an unnamed first-person narrator who speaks with a cool tone, is personally reserved, and observes character and emotion with insight and precision. The narrators practice the same profession: both are translators. They are also both outsiders in the settings where their stories unfold. Most of the action in A Separation occurs in and near Gerolimenas, a seaside village on the Mani Peninsula of Greece, far from the narrator’s home in London. Intimacies is set in The Hague, where the narrator has moved from New York City after her father’s death and her mother’s subsequent move to Singapore; previously, she spent her childhood in Paris and “long stretches” living in other European cities. And though their titles suggest that their subjects are opposing themes—separation in one and intimacy in the other—both novels show how our lives are bound up in the lives of others, including those from whom we wish to separate.

The narrator in A Separation has separated from Christopher, her husband of five years. Though they have been separated for six months and she is now living with another man, they have not yet discussed divorce, and Christopher has asked her to promise that she will tell no one about the separation. He never gives his reasons for asking her to keep their separation a secret. The narrator imagines that he “felt much as I did, that we had not yet figured out how to tell the story of our separation,” which perhaps says more about why she makes the promise—despite disliking its “air of complicity”—than about why he asks her to do so. He makes this request of her in their last conversation before he leaves for Greece to do research for a book he is writing on mourning rituals. A few weeks later, his mother, Isabella, calls the narrator looking for him; unaware of the separation, Isabella sends the narrator to Greece to find Christopher because, she says, “You know how powerful my intuition is, I know something is wrong, it’s not like him not to return my calls.” The narrator, realizing the need to “formalize the state of affairs” with her husband, goes with the intention of asking him for a divorce. Instead, he turns up dead from a blow to the back of the head.

Christopher’s death would seem to mean an end to the marriage, but instead the narrator finds herself bound to him through his family. Breaking those binds would seem to require that she simply tell the truth, that they had been separated and heading toward divorce. But rather than figure out how to tell the story of their separation, the narrator accepts her role in the story her mother-in-law tells to console herself. “At any rate . . . you loved him,” Isabella says to the narrator. “Despite his flaws. And that is something. He died loved.”

With her father dead, her mother a world away in Singapore, and no other family, the narrator of Intimacies appears, unlike the narrator of A Separation, to be entirely untethered. She accepts a one-year contract as an interpreter at “the Court” in The Hague with neither any intention of returning to New York nor any idea of whether she will stay in The Hague. Like her, the other interpreters at the Court “had lived in multiple countries and were cosmopolitan in nature, their identity indivisible from their linguistic capabilities.” Her friend Jana, a curator at the Mauritshuis, is also from elsewhere: born in Belgrade and sent to school in France during the war in the former Yugoslavia, where she has never returned. Her boyfriend, Adriaan, on the other hand, is a native, living in the upper floors of the townhouse where he grew up. The question dominating the novel is whether or not the narrator can—or wants to—make a home for herself in The Hague, possibly with Adriaan. Will her contract with the Court be extended, and does she want to continue to work as an interpreter there? And what is the status of Adriaan’s marriage to Gaby, who left him for Lisbon and another man half a year before the narrator arrived in The Hague?

One likely does not ever wish, however, to feel at home at the Court. There, the narrator is asked to serve as the interpreter for a West African ex-president who is on trial for atrocities committed against his people. This task brings her into an unwanted intimacy with him. In a conference room at the Detention Center, she speaks into his ear, translating the English of his defense team into French while sitting closely enough to him that she can “observe the texture of his skin, the particularities of his features . . . [and] smell the scent of the soap he must have used that morning.” In the courtroom, he makes a habit of looking for her in her booth from where he is seated for the trial and nodding to her, a gesture that at first startles and embarrasses her but soon enough becomes routine: “We would nod to each other and then we would look away and carry on.”

Like the narrator of A Separation, she finds herself complicit—in her case, in the defense of a man whom she believes is responsible for mass murder. But she sees a similar complicity everywhere. The Mauritshuis, where her friend works, for example, was founded by Johan Maurits “with a fortune built from the transatlantic slave trade and the expansion of Dutch Brazil.” Seeing how banal the Court’s Detention Center appears from a bus, she recalls a black site in New York City “above a bustling food court, the windows darkened and the rooms soundproofed so that the screaming never reached the people sitting below. People eating their sandwiches and sipping their cappuccinos, who had no idea of what was taking place directly above them, no idea of the world in which they were living.” Watching men clean up cigarette butts from a cobbled road in the Old Town, labor “necessitated by the heritage of the city, not to mention the carelessness of a wealthy population that dropped its cigarette butts onto the pavement without a thought, when the designated receptacle was only a few feet away,” she notes that “it was one example of how the city’s veneer of civility was constantly giving way, in places it was barely there at all.”

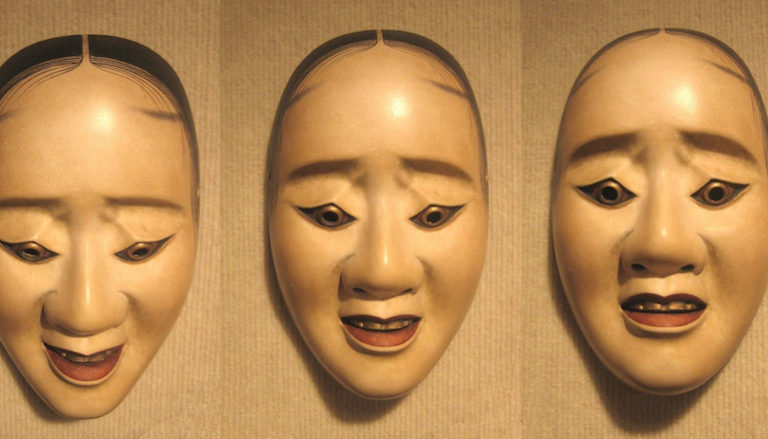

Both narrators are sensitive to these fissures in civilization, sometimes hidden and sometimes manifest, as in the landscape around Gerolimenas, blackened after a feud over stolen livestock led to fires that raged through the summer. Their work as translators occupies them with such fissures—the differences between languages, which could be like “great chasms . . . that could open up without warning,” says the narrator of Intimacies. To the narrator of A Separation, a literary translator, bridging this gap is an almost mystical act. “Translation is not unlike an act of channeling, you write and you do not write the words,” she says, and she admits that “the translator’s potential for passivity appealed to me. I could have been a translator or a medium, either would have been the perfect occupation for me.” For the narrator of Intimacies, this act of channeling can be harrowing. It requires her “not simply to state or perform but to repeat the unspeakable. Perhaps that was the real anxiety within the Court, and among the interpreters. The fact that our daily activity hinged on the repeated description—description, elaboration, and delineation—of matters that were, outside, generally subject to euphemism and elision.”

Eventually, the narrator of Intimacies questions the seeming equanimity of her colleagues: “They no longer seemed like the well-adjusted individuals I had met upon my arrival, instead they were marked by alarming fissure, levels of dissociation that I did not think could be sustainable.” Their well-adjusted appearances are just another example of the “veneer of civility” she finds so wanting in The Hague. The narrator of A Separation, too, finds instability in the self, concluding that both the past and marriage itself are “unstable realities”—turbulent, subject to revision. In the end, she cannot distinguish her experience playing the role of a grieving widow from actual grief—much like the grief experienced by the weepers of Mani, hired to perform lamentations at funerals.

Except through unsustainable dissociation, what is channeled cannot remain separate, it seems. It becomes part of the self. And so although the narrator of Intimacies agrees that she, like any other citizen of an imperial power, is neither blameless nor even so different from the former president, she also need not participate in his defense, or in the defense of others accused of atrocities. Unlike the narrator of A Separation, who assumes a role that enables her to revise the past, she decides to take a chance on the future. As she says early in the novel, “That was, I thought, the prospect offered by a new relationship, the opportunity to be someone other than yourself.”

This piece was originally published on November 3, 2021.