Lauret Savoy’s Trace and the Search for Self-Meaning

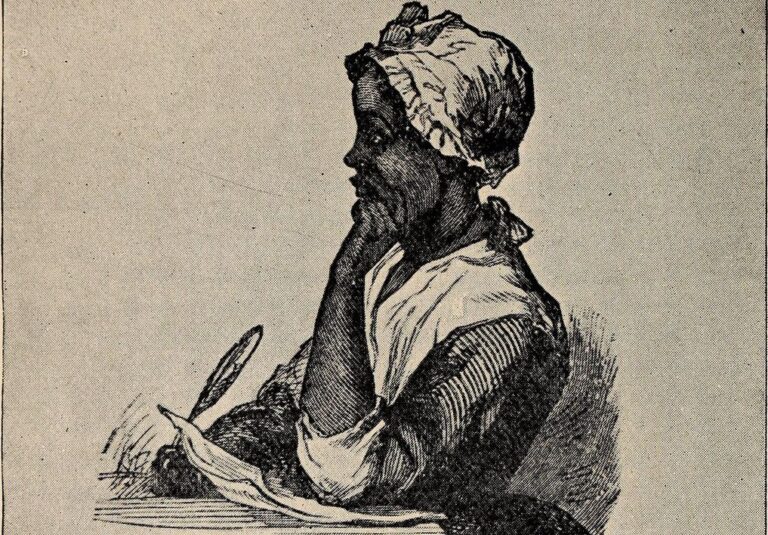

In her memoir-travelogue Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape (2015), Lauret Savoy, a professor and “mixed-heritage” woman of African, European, and Native descent, embarks on a road trip across the United States on a journey to “re-member” her ancestry and search for self-meaning. Faithfully following the conventions of academic research, Savoy journeys from state to state conducting genealogical research in libraries, archives, and museums, and pores over records that reek with the “mustiness of age.” But not finding her family in a rare archive of photos of African Americans in Colorado is only one in a string of disappointments that end with “knowing little” of the “origins” and “fate” of her third-great grandmother, a woman she discovers was named as “property” in a document detailing the inventory of a rich man who died in the early nineteenth century.

Such omissions and silences impede Savoy’s progress, but where she finds dead ends in the archives, her journey to “re-member” her family history is enriched through travel. At the juncture of Arizona and Mexico, Savoy finds that the border wall, or “La Gran Línea,” divides the town where her mother was once stationed at a now-defunct military fort from World War I—one of the only available stations afforded to Black nurses at that time. As Savoy contemplates the unlikely forces that brought her mother to a segregated army encampment on centuries-long contested soil, the divided border, with its outsized police presence, becomes a battleground for competing narratives where only some are clear victors. Whereas Savoy can readily consult the National Archives to find evidence of countless incidents of Jim Crow-era racism at the encampment where her mother was based, none of those instances are memorialized in the local museum. Instead, the Black soldiers, all “proud firsts” in their field, are praised for their “quiet dignity lacking outright protest.” Savoy imagines her mother’s “quiet dignity” on the other side of a photograph much like the dignity of those who live in the town divided by the wall—a dignity the border patrol officers, with their callous references to people on the other side as “monkeys,” refuse to acknowledge and see.

Travel thus becomes a means by which Savoy approximates truths not just about her own life, but the lives that make up our vast country. When Savoy can’t find recorded evidence about her ancestors, she asks us to consider the way distortions and silences in memorialized history implicate what we know of our individual pasts. From government records that name ancestors not as humans but cargo to unmarked and destroyed burial sites, the enduring legacy of erasure, assimilation, and genocide complicate the efforts of the descendants of Othered peoples to reconstruct the stories of who we are. What remains of history—both our personal ones and those archived in the libraries—are merely palimpsests, manuscripts so defaced with edits and revisions, you can’t see what was once written below.

Like Savoy, I have searched for “self-meaning” in places that reflect a warped image back at me. Born and raised in the United States, I am American in a way that differs from my grandparents, who immigrated as young parents from the Southern hemisphere to establish new lives on a landmass called Queens County. I’ve spent much of my life considering myself a “native” New Yorker, with little awareness of the land I grew up on and the people who have been rooted to it for thousands of years. Gaps in the history I’d been taught and reinforced in school contributed to my belief that I was, like the Buffalo soldiers described on the Fort Huachuca museum display card, among a rare group of “proud firsts”—“first-generation” citizen, “first to graduate college”—and perhaps also contributed to my vain, ahistorical belief that I was a “true” New Yorker, a designation I clung to lest anyone ever suggest that for this brown girl with a Castilian last name, home was somewhere else, far away. My American-ness comes with modifiers, a disclaimer that I offered proactively lest I get asked the dreaded question, “But where are you really from?” so in my twenties, I decided I traveled to Colombia—the country where my mother was born—for a year. And like Savoy, I sought traces of my ancestry through institutional knowledge—careful research and visits to university libraries—only to emerge unsatisfied. In Bogotá, tour guides led me around monuments celebrating Simon Bolivar’s heroic struggle for independence, but none acknowledged the much more recent war that accounts for the reason I know so many Colombians in New York. At the campus library, I looked for books written about the region my grandparents grew up in, but I found books imported from Spain. Eventually I began wondering why I had traveled so far, unsure of what I’d really gone to Colombia to do.

For Savoy, what’s preserved as institutional knowledge does not just exclude her family histories—it often invalidates them. Time and again, Savoy finds deliberate and harmful omissions in history: at Walnut Grove, one of the country’s largest remaining plantations, a tour guide flinches when Savoy asks about the enslaved people who once lived there. “The past is remembered and told by desire,” Savoy writes, and what most of us desire are stories that can be celebrated and uplifted—not those that are shrouded in upheaval and shame. Only such a distortion of the truth can account for why Savoy, as an “outdoors-loving child,” thought to tell her fifth-grade social studies teacher that she might be suited to work on a farm as a “slave.” But such grave deformations of history cannot withstand realities carved into earth, and when history fails, Savoy, a geologist, turns from institutions to the tactile land: a topic she can hold firmly in her grasp. Even as the truth of her origins remains out of reach, the “land’s composition and structure lay bare.” With her “reliable companions [of] sky’s brilliant depth and the tactile land” to remind her that home can be readily found in the natural world, her genealogical search is punctuated by a deep appreciation and enduring relationship with the country’s sublime geography.

Place—and developing a relationship to place—becomes key to Savoy’s journey for self-knowledge. Interspersed between visits to archives and libraries, Savoy travels across the vast expanse of the North American continent—to the inner gorge of the Grand Canyon, the boreal forests of Northern Minnesota, the Sonoran Desert—only to find that she has deep and enduring relationships to parts of the country she’s never stepped foot on. From a cottage on the Apostle Islands to the ancestral lands of the Anishinaabeg and the site of one of the longest ancient geological rifts, Savoy puzzles over the way the land had once imprinted upon her as a child through Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha. “So enthralled” she was to know a “real Indian story” that she hadn’t considered Schoolcraft’s role in helping the US government displace the Anishinaabeg for a state-sponsored search for copper and iron—and later for scientific research of its sandstone and volcanic rock terrain. In this distant history, Savoy, a geologist, recognizes herself: “I saw, too, that choices I had made in studies and work were somehow implicated in this pursuit of mineral wealth.”

It is through careful observations of the land that histories begin to emerge, and travel thus becomes a way toward self-knowledge. But Savoy reminds us that travel, especially to the remote landscapes that have so often captured the American imagination, can be a dangerous pursuit for many. Black naturalists and scientists continue to weigh their love for nature against the relative danger of hiking, recreating, or conducting science in their own backyards. Marjorie Leach-Parker, the first African American chapter chair of the Sierra Club in Virginia, admits to “never” hiking alone in the woods near her house for fear of the people who she might encounter there. Christian Cooper, who was famously harassed in 2020 while birding in Central Park, serves as one highly visible example of the fact that often the biggest threat in the wilderness that people of color encounter are humans. When Savoy reminds us that “place-names” provide clues about “who ‘we’ are to each other in this land,” she shines a light on the country’s violent history—and the way the land bears the scars. In 1963, the United States Board of Geographic Names decided to rename at least two hundred toponyms, replacing what it called the “pejorative form of Negro” with “Negro” itself. Places like “Negro Hill” in Loudon County, Virginia, were once not so inoffensively named. And though the “slur-name” is now gone, the wounds still remain, felt keenly as if on one’s skin, or as Savoy describes: “entraining me as water would a grain of sand.”

I have been called indígena in Argentina, white in Colombia, colored in South Africa, and Indian in the United States. Before knowing that genealogy was entrenched in white supremacy—derived from eugenics, the “race science” that upheld countless immigration exclusion acts—I knew that my culture could not be derived from my biological material. Collective memory did not live in samples of saliva or blood. Before I traveled to Colombia, across the Caribbean Sea, it was easy to perceive my heritage as nothing but “relics and ruins”—something that would be impossible to retrieve. But omissions can be filled with living culture; gaps in documentation and recorded history can be supplanted by the richness of the here and now. In Colombia, someone would introduce me to a vallenato I’d never heard, and suddenly I was able to glimpse into the lives of my grandfather’s family. Or I’d learn a Spanish expression from more than a thousand miles away only to realize that I’d known it my whole life in English. I didn’t find dusty, extant remains of my lineage stored in the archival boxes of a government office or underfunded library. Instead, I found ample evidence of what made my family the people they were—in stories and language and song. When your history has been, like Savoy says, rendered to “fragments,” the living tradition can restore what is lost.

“Illusions of rootlessness in one’s own home could only grow in such depleted and contested soil,” Savoy writes. “Elusive and illusive,” Savoy writes to describe the “ruins and shards” among which home resides. Elusive, but not impossible to find. Conversations, movies, and books can often make for objects of study. In Colombia, I hadn’t meant to collect oral histories, but with limited language skills and a deep interest to learn, I found myself constantly listening to people talk about their lives. I began to piece together in my mind a clearer vision of the country my forebears called home—the way collective trauma and violence could quickly foster alliances among strangers on a long bus ride, or how the Church’s outsized role in society could stand parallel with compelling and radical theologies. It wasn’t knowledge from libraries or archives that changed my relationship with my heritage. It was visiting the land—it was the travel itself.“I honored their elegies rather than the continuing presence of vital, fluid cultures,” Savoy writes of the child-self that once believed in what Dina Gilio-Whitaker calls the “myth of the vanishing Indian.” I once believed that to be hyphenated was to be less than whole, that to be part of the diaspora meant that a part of me, and my family, was irrevocably lost to migration, extinct and extinguished, gone. But if “home lies in ‘re-membering,’” then home is not a place, but an action, an ongoing process. To traverse land is to trace the steps of your forebears, and to travel in search of heritage is to access our past by living fiercely in the present and finding what stories live there.