Guest post by Carol Keeley

Before caravanning West with a couple of movers–who drove out from the mountains, arrived ripely hung-over, looked at all the boxes of books and 78s, then called local movers to off-load the gig–we lived half a block from a drive-through liquor store. Weeks earlier, a woman was shot dead in her car as two toddlers crawled the backseat. Each Halloween we got kids who were thrilled by our plump chocolate bars, plus crackheads. The kids had duct-taped fairy wands and masks that blinded them and the crackheads had plastic bags and gravestone teeth, stained hoodies, horrified eyes. We let them shovel candy into their bags. Most of them were neighbors.

Then, suddenly, sun-dazed Colorado was our front yard. The move was abrupt. We had to sell our house and find another within two months. So I shopped online and found handsome log homes with the Continental Divide framed in the kitchen sink window, and a skeptical realtor. After plowing through miles of mud, past tiers of mailboxes near a red dirt road, bumping along on Jeep trails for another hour or two, then reaching the dreamy homes with a view, I also found septic tanks and leach fields, propane tanks, mountain lion tracks, and a different species of people. I had to ask what a leach field was and am still grimacing. Glorious views, yes, but I was forced to confront my uselessness. People deep in the mountains were robust, weathered, Emersonianly self-reliant. Despite all the space, they lived in tight clusters, like circled wagons, with jerry-rigged plumbing and electricity, survivalist food supplies.

I, on the other hand, am frightened by fuse boxes and acquired the habit of shopping daily for fresh produce while living in Paris, preferably by walking a few charmed city blocks with a mesh bag.

So we didn’t end up living in a mountain town like Ward, which features front-yard piles of decomposing automobiles, a single restaurant that doubles as the church, Tour de France fans in seallike garments huffing up the brutal hills, vistas that obliterate language and winters that obliterate faux pioneers. The mountains do not suffer fools. That’s a trait I appreciate. But people die regularly here, many of them experts. They’re expert climbers, expert skiers, some are even expert rescuers.

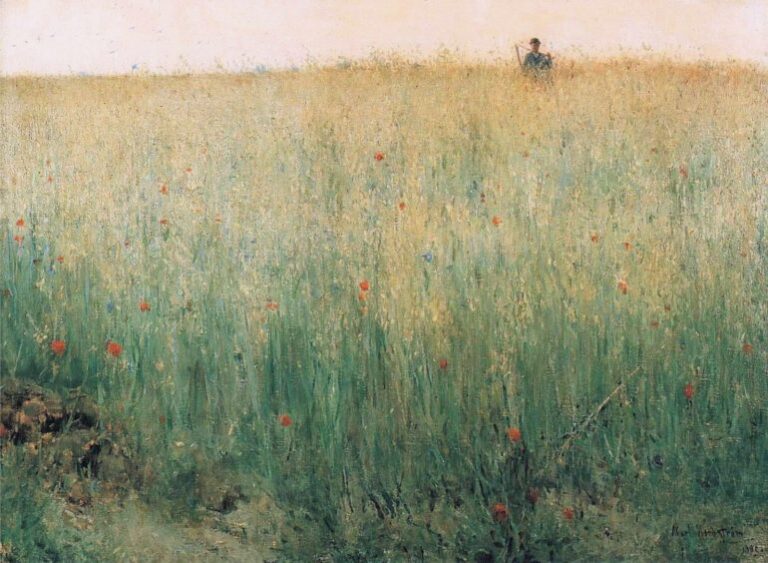

Nature kills without malice. I respect the deadliness of nature, which is different than crackheads and liquor store shootings and failed levies and flaming towers. It just is. Only man is capable of inhumanity. Nature commands reverence and humility.

Initially, the West terrified me. Too much space, too much silence. I lived on Chicago’s Belmont and Clark when it was Mecca for teen runaways and addicted drag queens; then I lived in a crack neighborhood on the cusp of gaslight idyll. Sirens were constant. Suddenly, I’m in Colorado, paralyzed by advice on dealing with bears and trailhead warnings of fresh mountain lion kills. I’d dealt with gunshots and sirens and junkie drag queens, full moon crazies. But lions and bears scared me.

I was even more unnerved by how friendly everyone is, though I’ve since learned this varies as sharply as it does elsewhere. People living in the small, monied mountain towns and hikers on serene backwoods trails–incandescently friendly. People burrowed in the mountains out of self-isolation or a belief that the government is a single malevolent entity–unhinged. And armed to the gills. Parts of the West are as obscenely wealthy and class-stratified as pockets of Manhattan. And parts attract people who dwarf my misanthropy, which is of the urban variety: I love cities because I want to ignore people but still encounter them.

A real mountain town, the tough-to-reach ones, are dotted with people who embody both rugged and individualism. Front porch furniture is made of recycled skis or old metal chair lifts, an abandoned train car becomes a café, and drafty shacks corniced with prayer flags serve Nepalese family recipes. Most aren’t actually towns. One is a Home Rule Municipality, which consists of forty families and a lone diner whose cook left the kitchen to make sure my dog had enough water and something to gnaw. Driving through on black-diamond grade dirt roads, these places seem post-apocalyptic. But one such village boasts the most doctorates per capita of any town in the U.S. People choose to live in such places, often right next to other people, and it isn’t just for the vistas. Something else drives them. Some need contact with nature, what it nurtures, what it demands. Some need self-sufficiency. A woman in one of these mountain towns told me their neighbors waited until they’d lasted three winters before welcoming them. These are essential Americans, real pioneers.

“The best was the men,”

said Walt Whitman of the brawling town of Denver, “large, able, calm, alert, American.” He

called the Rockies “America’s back-bone,” and the vertebrae of our hemisphere. Specimen Days conveys the rapture of seeing this landscape for the first time. “I have found the law of my own poems,” he

wrote. “One wants new words” for this, “the most spiritual show of objective Nature I ever beheld.” Though written two centuries ago, his praise applies still. “New senses, new joys, seem develop’d,” he said, as he savored “the cool-fresh Colorado atmosphere,” and the evidence “of man’s restless advent and pioneerage, hard as Nature’s face is.”

I love the resourcefulness of people here. Sponsored by

Center of the American West, Annie Proulx made a rare appearance to talk about Wyoming’s endangered Red Desert. That night, there was a savage blizzard. Like everyone else in the auditorium, I arrived on snowshoes. It was the only mode of transportation. All were dressed in Gor-Tex; many had avalanche headlamps. The place was packed. Patty Limerick, the Center’s enviably named director, announced that the blizzard had been arranged to insure Proulx an audience of “hearty, tough, persistent, intrepid, true Westerners.”

There’s a distinctive spirit in the West. It’s irreverent, disciplined, somehow boyish. Example: I had the sewer line scoped, since shifted pipes are an issue here, and we’ve old-growth trees, including a four-story spruce. The lad arrived with a truckload of equipment, a filthy hat, elegant hands, a flashgrin. On the backside of thirty. Finding access involved scrambling through wild brush and onto the roof, all of which he did nimbly. After sitting at the kitchen table with a beer, fiddling with his computer, he handed us a film of our sewer line on a meticulously captioned DVD–tree roots, a slight fissure, the city line–along with a fresh bag of popcorn. Date night.

And here’s us, right after tumbling off the moving truck, walking up and down a dark street trying to find the address of a couple who invited us for dinner. He’s a brilliant musician who grew up in Brooklyn but prefers living simply and near nature. Pianists come from all over the world to study with him. His wife apprenticed with Ginsberg. The Beats still occupy this bucolic town, as do many Tibetan Buddhists. It’s where they first cross-pollinated, the Beats and the Buddhists. We can’t find any addresses. I’m cradling flowers and squinting into the darkness. Suddenly a porch light snaps on. We stand there, deer-frozen.

Hand painted in purple script right on the house: DOORBELL HERE, with a plunging arrow. We gingerly step onto the porch. Music’s pouring out the windows–a good sign–so I hunt for the doorbell. Following the arrow leads me to a hip-high metal can. “I got nothing,” I report, then realize the can is the doorbell. It’s upside-down with a battered bum, drum stick attached by a string. An ersatz steel drum. Brad grins and starts playing it. He plays a doorbellish tune. And so begins a magic evening that includes several courses of delicious food, an extended jam session in the house built in back of the house, during which a basket of stuff, including a toy accordion and a crocodile whistle, gets emptied out and employed; I play sitar and gong, but decline to read aloud randomly from The Inferno.

The family across the street from us was nudist, their little boys shoving out the door to piss proudly in all directions; but they were from Alaska and found it hectic here. Too many laws about guns and clothing. They soon moved deeper into the mountains. Now we have fellow idiot urban escapees whose chickens escape regularly. We keep finding bird bones in our yard, along with foxes.

“In New York, the music is about itself,” says the pianist. “Art becomes tautological. Here you can go for a hike, meet someone, have a long conversation, and all of that goes into your music.” This is true for him. He makes music for the pure playful joy of it. Once, after a late October meal, we went Halloween caroling house to house on his block, looking and sounding a bit like a haywire circus. I’ve never met people more spontaneous, more fearless. There’s a cultural blending here of discipline and lawlessness.

It’s not just him. My dentist is a triathlete who bikes forty miles round-trip to the office, whatever the weather, swims while the office is closed for lunch, then runs the mountaintops on weekends. One morning, he removed my cracked wisdom tooth, literally dripping with sweat and rain, having just jumped off his bike. The joint shutters up for several months a year to do what he gaily dubs “jungle dentistry” in refugee camps throughout Asia. He comes back with pictures of radiant kids, appalling conditions. And sometimes he comes back with a refugee. Currently, a Burmese couple lives with him, struggling to learn English and cleaning my teeth with earnest tenderness each time I stop by. My optician is also an athlete and a professional nature photographer who does free cataract surgeries in the Andes, where people are literally blinded by the sun. It’s the land of the überfit and the actively compassionate.

While snowshoeing up Bear Canyon after yet another blizzard, a couple in

their mid-eighties asked if they could pass us. “Knock yourself out,” I grumbled. We spotted the man’s arm cast. Skiing, he shrugged, then grinned. His wife had to do all the shoveling. Turns out they retired here, not to lure their kids for visits, but to ski and hike and see Shakespeare outdoors and hear free concerts.

We see Frank and Maureen regularly at jazz gigs now, but I refuse to hike with them.

This town is known for its extensive Open Space, hiking trails and wild beauty, which means most homes are unaffordable, except in this neighborhood. We’re in crumbly post-war ranch homes, a mix of original owners, college kids, and the scrappy rest of us. Down the block is a public school teacher and his wife, a counselor, their kids. The teacher is also a blues musician. He rolls about on a comedically tiny bike, wearing a jaunty straw fedora. The teacher/musician is also a film maker. His latest is a documentary about our scruffy neighborhood, the premier of which was in the old community pool. It made an ideal screen, so has become an ad hoc theater.

When a neighbor to our right had her second son one winter, she didn’t cook for the first month. People delivered hot meals to her door every dusk, including something her four year old would eat, and a treat for their giant Akida. One enterprising neighborhood gardener asked if folks wanted to surrender their lawns in exchange for a free weekly box of produce. This launched a new variety of community-supported agriculture, which was written about in the Wall Street Journal and has spawned happy imitators. Each week, what isn’t sold at the farmer’s market or redistributed to the lawn-lenders is set out in a cooler on the gardener’s front porch. You can go help yourself to gorgeous kale, cilantro, salad greens, rosemary. In the fall, we drop our leaves off at his house to recycle as mulch or compost.

Our house isn’t special. It’s got one small bathroom. The laundry room used to be in the kitchen, where mold lingers. The yard attracts wild animals. Many nights, the dog refuses to go outside. But I can cross a street and be in the mountains and this neighborhood is a true community. One Thanksgiving, while forty family members converged for lunch, our pipes burst from the cold, turning the joint into Water World. A giddy niece ran outside hollering and three able Coloradans came running, armed with grins and wrenches. One jumped into our crawl space, another turned off the water supply, a third offered use of his blowtorch. And the city folk stood uselessly by, swoony with appreciation.

Recent samples from our neighborhood listserv:

Free magic tricks. My son lost interest.

Anyone have an old garage door opener to use with a chicken coop?

Crab apple tree in front yard looking for a new home.

Hi all, I am looking to drill a 6-inch hole into plexiglas. Anybody out there have a 5-6 inch hole saw I could borrow for an hour? It would be much appreciated, and I could offer a beer or something in return.

When I used the listserv to ask about the cement incinerator in the backyard–used here in the Fifties in lieu of garbage pick-up–I got phone numbers for cement removal specialists, conversion ideas, plus a note from a woman in her late seventies, who said she just got rid of hers last summer. Used a sledgehammer. Felt good. Paid a neighbor kid to haul off the pieces.

I want to be her when I grow up.

I can’t pretend to know anything about the West. It takes eight generations to earn the right to call yourself a Parisienne. To be a Westerner takes longer, and rightly so. Living in Paris taught me how American I am; Colorado is exposing my Midwestern roots. But there is a specific snow-cupped mountain here that affects me deeply. When I mentioned this to a Ute Indian one night, he just nodded. That mountain will keep calling you home, he said simply. Once she touches you, you always have to come home to her.

This is Carol’s fifteenth post for Get Behind the Plough.

Images: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7