Guest post by Scott Nadelson

The first time I saw

Be Here to Love Me, the documentary about songwriter Townes Van Zandt, I was in rough shape. This was in 2005. I’d recently gone through a devastating break-up, which left me reeling and broke, living in an attic apartment whose ceiling was infested with squirrels. For months I hardly went out, spending day and night reading books, watching movies, drinking, and listening to music obsessively. My credit card was nearly maxed, but there was a record store within walking distance of my apartment, and every couple of weeks, when I was feeling especially down, I’d treat myself to something new. When I brought it home I’d play a single track over and over until I could hear it in my head as I walked down the street or shopped for groceries or lay awake in bed, staring at the ceiling. It was a sort of meditation tactic, I suppose, a way of crowding out thoughts I didn’t want to indulge.

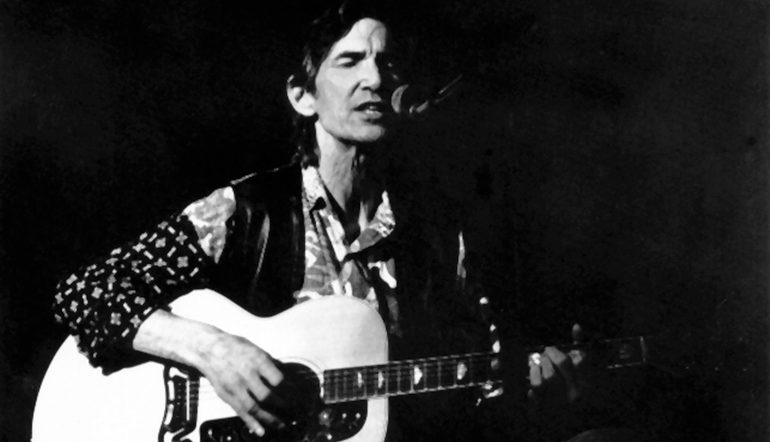

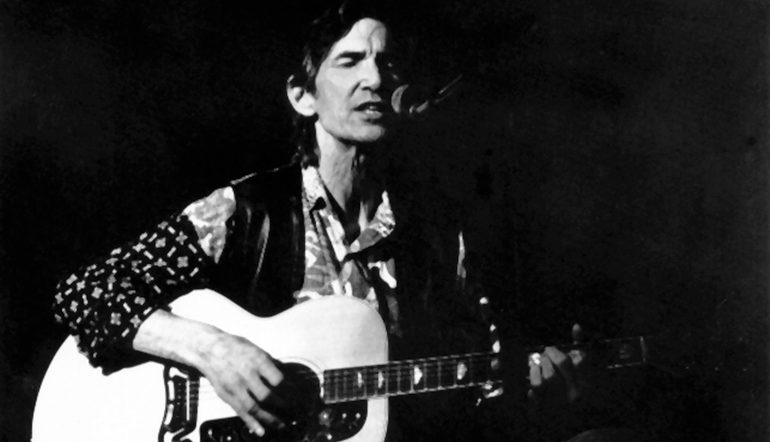

The music I was into ranged from Eric Dolphy to Steve Reich to the New York Dolls, but more than anyone else, I listened to Townes. I’d been a fan for years, but since my life had fallen apart, and in the state of despair and slow recovery that followed, I had the feeling that his lyrics were addressed to me directly. “Everything is not enough, and nothing’s too much to bear,” he’d sing, and I’d nod and pace my attic’s splintered floorboards. “The dark air is like fire on my skin, and even the moonlight is blinding,” he’d sing, and I’d huddle down in my frayed, second-hand sheets. “Lay down your head awhile, you are not needed now,” he’d sing, and I’d forgive myself for hardly having left my bed in months. His ballads were mournful, but his voice was casual, with a mixture of wisdom and resignation and reckless bravado, as if he couldn’t take all this mournfulness too seriously. Life is tough, he seemed to be saying, but you can take it. At the time, that was the only message I wanted to hear.

When the documentary came out, I went to see it alone–as I did dozens of movies at the time–in a rundown theater in southeast Portland that showed only those independent films guaranteed to lose money. To my surprise, though, the theater was packed, though half of its seats were broken. I usually liked to keep a few spaces between myself and strangers, but now I was stuck sitting next to a young couple who held hands through the entire movie. They were maybe twenty-four, both pink and chubby as babies, the boy with a patchy beard, the girl with her hair in pigtails. They were too young to appreciate Townes, I thought, too happy to understand the songs. But whenever one came on, they sang along, too loud and too fast, making clear to everyone around that they had the lyrics memorized. Not fifteen minutes in I was ready to strangle them.

The film was unquestionably tragic, I thought, a story of missed opportunities, of disappointments and failures, of unrecognized genius, of life cut short. About a third of the way through we see footage of Townes in the mid-seventies, at the height of his creative powers. By then he’d written most of his best-known songs, including those that would become big hits for other people: “Kathleen,” “If I Needed You,” “Pancho and Lefty.” He should have been a household name, but he wasn’t. He didn’t play to crowds of thousands. He didn’t ride in limousines or private jets or even a lavish tour bus. Instead he was living in a beat-up trailer outside Austin, drinking whiskey straight from the bottle, wrestling with a mangy dog, and shooting at tin cans. And yet his words could bring a man to tears.

Here was easily the best songwriter since Dylan, completely neglected by the world, almost entirely unknown. His albums would never sell more than a few thousand copies, and most would go out of print. He’d be screwed by managers and record companies and die at fifty-two, his body ravaged by booze. Only after he was gone would he be rediscovered, his albums returned to print, his name mentioned in interviews with more famous songwriters, his songs played in hip coffee shops all over Portland, his lyrics memorized by irritating young couples in love.

Hunched down in my broken seat, with loose springs pricking my thighs, I could think only that the world was terribly cruel, that no one got what he deserved, that I should never bother to leave my apartment again. I was on the verge of tears, and if that couple hadn’t been right next to me, the girl’s popcorn balanced on the armrest between us, I might have wept openly during Townes’s funeral, when his best friend and fellow songwriter, Guy Clark, walks to the altar and says, “I booked this gig thirty years ago.” At the movie’s end, the two lovers looked into each other’s eyes for a good forty-five seconds, in some kind of communion, as if the film had affirmed them in their love and happiness and bright future together. They kissed all the way through the credits, and I left the theater in a rage, believing I was the only one who’d actually seen the film, just as I often thought I was the only one who really heard Townes’s songs.

I continued to listen to those songs even as my life began to turn around, as I left the apartment more often and re-awoke the world, and they meant just as much to me when I wasn’t drinking or huddling in bed. “Heaven ain’t bad, but you don’t get nothin done,” Townes sang as I went through days with renewed promise and hope, throwing myself into writing and teaching and connecting with friends. “To live is to fly, all low and high,” he sang when I met my wife and moved out of my attic. “If you needed me, I would come to you, I’d swim the seas for to ease your pain,” he sang at our wedding two years later.

But as essential as the music was to me, I didn’t want to watch the documentary again. Townes’s life story was too heartbreaking, I decided, the film too focused on his addictions and gambling, his shortcomings as husband and father, his failures rather than his triumphs. It detracted from the beauty of the songs, of the genius of the writing. You didn’t have to know anything about a person to appreciate his accomplishments, I thought; the work should be allowed to stand on its own.

And yet, something about this way of thinking didn’t fully satisfy me. All these years I was haunted by that image of Townes outside his broken-down trailer, talking about huffing so much glue that his teeth stuck together and had to be knocked out with a ballpeen hammer, and I was never able to separate it entirely from the songs, or from memories of the two bleak years I spent in that attic with the squirrels scurrying overhead. There’d been something crucial about sitting in that rundown theater, about watching Townes’s drunken antics, about wanting to strangle the happy young couple next to me, though I wasn’t entirely aware of it at the time and couldn’t quite put my finger on it now. Maybe because five years had passed, and because I now looked back on that dark period of my life mostly with amusement and faint nostalgia, I found myself wondering often about how I’d react to the film today. Whatever the reason I felt compelled to rent a copy of it last week.

And even then I hesitated to watch it. It’s terribly sad, I warned my wife. You probably won’t like it. It sat on my desk for a few days, and whenever I glanced at it I’d think, no, not yet. I knew what my reluctance was about. I no longer wanted to believe that the world was cruel, that no one got what he deserved, that life was a long series of disappointments. Even if it was true, I’d rather remain in denial, to think of Townes only as a brilliant songwriter who was properly revered–by me, at least–and not as one who was still underappreciated and neglected.

Eventually, though, my curiosity outweighed my misgivings, and this past weekend I watched the film again. About halfway through, I glanced at my wife, who gave me a look that suggested she didn’t see what was so tragic about the story. Yes, Townes was a mess; yes, he’d had his childhood memories erased by insulin shock treatment; yes, he abandoned his first family for the road and drank himself into an early grave. But he also threw himself into life, with a passion and dedication that was impossible not to admire. He was drunk but charming, telling jokes, shrugging off disappointments, at times not lucid enough to remember which songs he’d written, at other times articulating very clearly how much he cared about language, how carefully and precisely he selected every word. There was still sadness in the film, and I still got choked up when Guy Clark took the stage at Townes’s funeral; but there was also joy, and humor, and above all, the incredible beauty of the songs.

Five years ago, I’d seen only half the film, my own sadness blinding me to the rest. The young couple beside me had likely seen only half, too, and sitting beside each other, we might as well have been in two different theaters. It amazes me to think what we carry with us into the world, the very air around us subject to our states of heart and mind. One day we “welcome the stars with wine and guitars,” and the next, “even the moonlight is blinding.”

This was what I’d missed somehow the first time around: Outside that broken-down trailer, Townes didn’t care at all that his albums weren’t selling, that he wasn’t a household name. He didn’t care about private jets or lavish tour buses. He had his songs, and his dog, and his friends, and his guns. He laughed a drunken laugh. He showed no sign of wanting to be anywhere else.

This is Scott’s seventh post for Get Behind the Plough.