“Listening to my friends is one of my favorite ways to write”: An Interview with Durga Chew-Bose

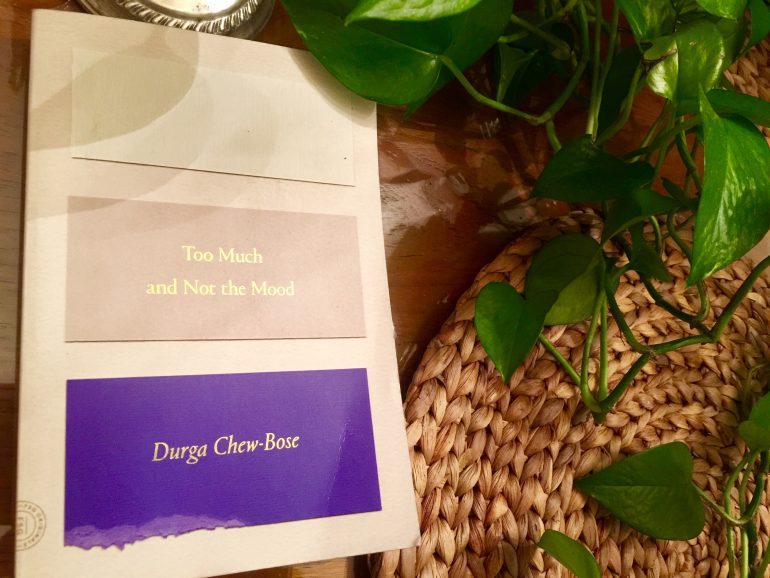

Durga Chew-Bose’s new collection of essays, out this month from Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, is a probing cataloging of a writer’s interior life, the observations and connections she makes as she writes her way toward understanding. Too Much and Not in the Mood takes its title from a line in Virginia Woolf’s diary, in which Woolf says that the tiresome process of rewriting The Waves leaves her nothing left to say, or else too much, which she’s not in the mood to say.

Chew-Bose also has in common with Woolf her associative and discursive style of examination, holding up each thought to a lens and turning it from side to side. Reading this book is like listening to conversations outside your bedroom window, snippets and remarks without a clearly identifiable beginning, middle, or ending. From her childhood in Montreal, growing up as a first generation daughter of an Indian family, to her young adulthood in Brooklyn, Chew-Bose’s non-narrative essays are drawn in a loose fistful of belonging together—the heart motif in her opening essay (about an emoji, the Tin Man, Build-a-Bear, and her father’s cardiac surgery, among other heart-related musings) or her memories of the complex role of a daughter to faraway parents.

The narrative of her life is largely off the page; the reactions and reflections are what surface. Of her grandmother’s hospital room she writes, “But even in hospitals, sunlight is beautiful. . . . And the humiliation of loosely tied gowns and bare skin, and elastic waists, even those degradations fade when the light pushes through the blinds and discovers bare skin, not to shame but to warm.” It is not possible to predict where we will go next since we follow a mind rather than a story. “To want and to write in the first person are two actions that demand of you you,” she writes in an essay about the first initial of her name, which she shares with generations of women in her family. “But this long and lanky ‘I’ has never arrived at me freely. How can ‘I’ contain all of my many fragments and contradictions and all of me that is undiscovered? . . . Writing in the first person necessitates that you grow fascinated with yourself.”

Too Much and Not in the Mood demands we lean in and listen, to read and re-read entire sections, to put it down to think about our own manners of indexing memories and observations, to let it all steep and brew. Because so much of Chew-Bose’s collection is informed by what she has read, I asked her a few questions about the process of discovery in pages she reads, and how that translated to the pages she has written.

Ellen O’Connell Whittet: I’m always interested in the genesis of people’s writerly identities. Can you say any book or books in particular might have contributed to your thinking you have a story to tell? In what ways, and to what extent?

Durga Chew-Bose: Marguerite Duras’ The Lover. Because the book’s unnamed narrator is preoccupied with memory’s haunting appeal, but also memory’s prophetic powers. The little clues we pick up when we look back. It’s also a book that considers writing as a series of contradictions. And writing as . . . women.

Frank O’Hara’s poems. Because his enthusiasms feel plenty. Because images seemed to spring up from inside of him, without necessarily stringing together neatly. The effect is light but also, somehow, sad in that it’s impossible, really, to retrieve anything, ever.

The way Manny Farber writes about film, the way Hilton Als writes about family, the way Fanny Howe in Radical Love writes about soul and beauty, and fear as one’s loveliest feature. May Sarton’s Plant Dreaming Deep and Journal of a Solitude. James Baldwin’s The Devil Finds Work. Lynn Tillman’s The Broad Picture.

EOW: There are mentions of books peppered throughout this collection—John Gregory Dunne’s novel Monster, your childhood best friend being your “first Diana Barry,” an entire chapter devoted to reading Moby Dick in the library of your college. The title of the collection comes from the final line in one of Virginia Woolf’s diaries. What other books, that don’t get direct shout outs, have made their way into these pages? How have you made a home for their influence?

DCB: Other books that inched me closer to believing, me too, I have a story? In Seduction and Betrayal, when Elizabeth Hardwick writes about being moved by Woolf’s The Waves. I found it touching and also rare to read about awe. It made me want to write because so much of my experiences, the ones I remember at least, involve appreciation. Or maybe I just confuse seeing with appreciating?

EOW: Is there any difference to how or what you read when you’re in the midst of writing? What is your reading process when you’re in the middle of your own writing process?

DCB: I spent much more time re-reading while writing the book. As if to remind myself of some original purpose or original love. I also read what my friends were writing, which some might say was ill-advised. But knowing what they’re thinking about or upset about, or what images they are connecting or what’s currently meaningful to them, helped. It provides context for the world I live in. It reminds me of their textures and how reading them felt similar to talking with them, which often feels like a version of writing. Listening to my friends is one of my favorite ways to write.

EOW: What kinds of writing were they doing that mattered to you?

DCB: I kept up with what they were writing, reporting, sharing online. A lot of my friends are writers, so I wanted to stay aware of what was preoccupying them; sort of like receiving dispatches.

EOW: We’re in a political period of deep dissatisfaction and censorship. What would you assign Americans to read, either as guidance, history, or inspiration?

DCB: Everything Doreen St. Félix writes. Alice Walker’s Anything We Love Can Be Saved. Tommy Pico’s poetry. Solmaz Sharif’s Look. Jia Tolentino. Masha Gessen. Arundhati Roy’s 2002 talk at the Lensic Center titled “Come September.” James Baldwin, June Jordan, Angela Davis, Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. Jenny Zhang. Ayesha Siddiqi. Paul Beatty’s The Sellout.

EOW: If you had to assign reading to anyone working on a book, what would you assign? When you experienced burn out or discouragement, what kind of reading would re-inflate you?

DCB: Interviews between writers can be very helpful. I love getting completely lost in the Paris Review’s archive of interviews online. Also artist writings like Agnes Martin’s. Renata Adler for rhythm, attitude; revisiting Speedboat was invigorating. Virginia Woolf’s diaries for feeling less alone and pushing through those days of thick doubt. Sometimes too, a good novel is all I need to climb out of my head. I remember speeding through Dana Spiotta’s Innocents and Others and Claire Louise-Bennett’s Pond. But maybe most of all: poetry. Especially in the afternoon when you need that second wind.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.