Guest post by Carol Keeley

It began, like most obsessions, in a used bookstore on Broadway. Late one afternoon, I was listlessly foraging for food and stopped to browse pre-loved books in my old Chicago neighborhood.

I venture to say that most people most of the time experience the same four-o’clock-in-the-afternoon devaluation. [But] if such a person […] should begin reading a novel about a person feeling lapsed at four o’clock in the afternoon, a strange thing happens. Things increase in value. Possibilities open. This may be the main function of art in this peculiar age: to reverse devaluation.

We found each other suddenly:

Conversations with Walker Percy, a compilation of interviews so compelling, I sat on the floor reading as people stepped over me. It’s one of nearly 140 volumes in the

Literary Conversations Series, published by the non-profit University Press of Mississippi. Each book features thoughtfully curated interviews, uncut and often unavailable online. At the time, I was in the flush of a Percy crush and the book was a passport into his working mind. It revved me as a reader and as a writer.

“Nothing helps in heaven or earth when you’re writing,” says Eudora Welty. “It’s just you out there by yourself. That’s the way you want it.” Very true, but her interviews are generous guides to everything from writing dialogue to the tricks of revision. You have to excise the “pet thing,” she says. But:

There’s something you don’t want to lose, which is the freshness and spontaneity of the original burst forward. You don’t want to lose it, even if it means for flaws of one kind or another. You can correct with gentle revision, but leave the sense of that headlong feeling of a short story.

Then she laments not writing “as headlong as I would like.” I’ve yet to catch any writer in this series thinking they’ve a clue what they’re doing, which makes one’s own midnight despair a bit less oppressive.

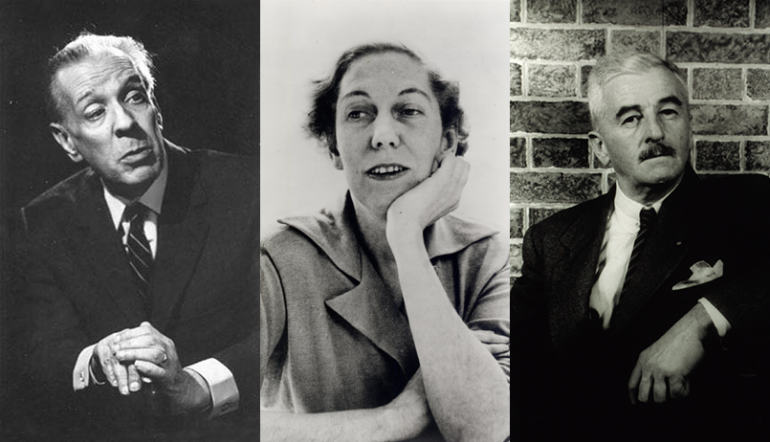

Like other writers in this series, Welty resists interviews and seems uncomfortable when they begin. This changes over the course of each conversation, as well as across her decades. For me, these volumes serve as translucent biographies because the writer is less mediated and abridged. There’s parrying: Welty is deflectively deferential. “I don’t know. I’m really not very knowledgeable of it,” she’ll say, then ask the interviewer what he thinks. Tennessee Williams makes his guest another martini, gets distracted by the mention of a play he can’t find and suddenly wants to finish, calls friends in Key West to find it, panics when he can’t reach his house-sitter and calls hospitals in Florida to see if she’s there. Wendell Berry’s interviewers help him with farm chores, feeding the draft horses or milking the cows. Jorge Luis Borges spins a filled auditorium with a concise burst of wit. Everyone forgets the question. But even privacy’s devices are revealing and endearing. And there’s chemistry at play in each case. Williams is witheringly curt with many, then opens up like an orchid with Studs Terkel. The infamously cagey Faulkner was loquacious at West Point, where each question was prefaced with “Sir.”

The indexes allow you to zoom in on specifics, while the books as a whole bring you into each writer’s process and solitude. Even self-destruction unfolds readably. Some writers deteriorate, catch themselves and rebloom across a bookspan. Some can’t break the spiral. Williams returns obsessively to his brother Dakin, “notorious for his political maneuvers,” and an ex-agent; they had Williams institutionalized briefly during what he calls his “stoned age.” This tale is bitterly revised over the course of countless interviews. But then he drops the façade and says:

My public self, that artifice of mirrors, ceased to exist and I learned that the heart of man, his body and his brain, are forged in a white-hot furnace for the purpose of conflict. That struggle for me is creation. I cannot live without it. Luxury is the wolf at the door and its fangs are the vanities and conceits germinated by success. When an artist learns this, he knows where the dangers lie. Without deprivation and struggle there is no salvation and I am just a sword cutting daisies.

The rapt interviewer concludes “There isn’t much to say after that.” So does the person who hears this exact speech two years and one hundred pages later. And anyone who’s read “The Catastrophe of Success.” It’s verbatim. It’s the ouroboros of the self-quoting author.

There are colorful tales by Faulkner, Jim Harrison, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, who demurs that he does so out of affection for journalists. Faulkner toys with interviewers, telling one that he’d joined the Canadian Air Force in World War II and flew a combat mission after only two hours of training, tailed by an expert German fighter pilot–gripping details of the dogfight are provided–which ended when he plowed into “the ground about a hundred miles an hour.” The interviewer, fizzed by this get, asks if the engine landed in his lap.

“No,” said Faulkner pleasantly. “I came to hanging from the belt….I never did figure out how I broke my legs.”

He tells another reporter that he was recently “awakened by the damnedest ruckus you ever heard.” Faulkner slipped on a robe to investigate and found the possum had tried to escape, but didn’t get far before “every dog on the place, the two cats, and Jill’s horse had formed a circle around that possum, holding him up the tree.”

The dogs were yipping and the cats yowling, declared Faulkner, until Uncle Ned put the possum back in his cage. The interviewer asked sardonically, “The horse wasn’t whinnying?”

“Of course not,” replied Faulkner. “It just isn’t in the nature of a horse to whinny when he trees a possum.” Just as it isn’t in the nature of a storyteller to let someone else take the reigns of his story. Walker Percy interviews himself, and Thomas McGuane and Jim Harrison pretend to interview each other. These antics are in the tradition of Mark Twain’s revenge on the “peart”

interviewer. When these conversations aren’t delivering intravenous-grade advice on writing, they’re glistening with gems like these bits of misbehaving, plus hard-won wisdoms and harvested revelations. In moments, you feel deliriously near each writer who’s speaking.

These books are also filled with faceted details, like Faulkner’s California kitchen, where his “majestic” maid from Oxford sweeps the floors and cooks with a pipe in her mouth. And the fox and raccoon pelts draped over cross-beams in Harrison’s office, once a granary, and the handwritten commandment tacked to one wall: “Keep it Vivid.” And how Eudora Welty picks up her interrogators at the airport. “It’s just a few minutes away, it’s the easiest thing in the world to meet you.” Then after a much longer drive than advertised, offers a meal of “ham and snap peas and grits and salad out in the kitchen. Will that be all right?” And how Walker Percy serves iced tea in “Kelly green glasses (the kind my mother used to retrieve from oatmeal boxes)” and the interview is interrupted by a call from a stranger reading one of Percy’s books who demands to know what “satyriasis” means. After many tightly controlled interviews, you gradually learn that Percy’s Uncle Will wasn’t an uncle but a distant cousin, a bachelor lawyer-farmer-poet who raised Percy and his brothers after their father’s suicide and mother’s fatal car accident, and that Uncle Will wore kimonos at home. You learn that Faulkner was ashamed of Sanctuary because the book’s conception “was shameful,” his “whole intention was base,” and the book wasn’t “honest.” You hear Williams blurt, “I have a codicil in my will that when I die I am to be pushed off a ship where [Hart] Crane went down.” Then he snaps opens the fan Crane’s mother sent him. Whether this is true doesn’t matter. It’s all molten reality, like literature.

“I always get rather angry at those who speak of reality on one side and of literature on the other as though literature were not a part of reality,” says Borges. “If you read a book, it’s as much of an experience as if you had traveled, or if you were jilted.” Welty dissolves another binary: “Does life give literature meaning or does literature give life meaning? I don’t really separate them. The life blood of one is in the other.” And Wendell Berry dislikes the term “environment” because it’s also based on:

that dualism, the idea that you can separate human interests form the interests of everything else. You cannot do it. We eat the environment. It passes through our bodies every day. […] There is no distinction between ourselves and the so-called environment. What we live in and from and with doesn’t surround us

–it’s part of us. We’re of it and it’s of us, and the relationship is unspeakably intimate.

St. Paul’s claim that “we are members of one another” is fully inclusive for Berry. He is a mesmerizing homilist of community, environment and interrelationship. “The work of the imagination, I feel, is to understand this.”

Each writer insists the work speaks for itself and is weary of interruption. Being a writer, growls Faulkner, “doesn’t make what I eat for breakfast or think of the international situation a matter of news or public concern.” Parts of Walker Percy’s interview with himself, “Questions They Never Asked Me,” are justifiably crabby:

Q: Would you comment on your own writing?

A: No.

Q: Why not?

A: I can’t stand to think about it.

Q: Could you say something about the vocation of writing in general?

A: No.

Q: Nothing?

A: All I can think to say about it is that it is a very obscure activity in which there is usually a considerable amount of malice. Like frogging.

Frogging, of course, being the art of conjuring charley horses with a knuckle, a skill intrinsic to brothers. This same interview reaches nearly harrowing depths of honest insight about how a “novelist these days has to be an ex-suicide” and the sorry trend of certain male writers. “The formula is: Big pencil equals big penis. My own hunch is that those fellows have their troubles, otherwise why make love with a pencil?”

We find out more about the genesis of individual works–which just deepens the reverence–as well as what sits on these writers’ desks and how they work and who they read. They all read copiously. They read contemporaries and classics. Even blind Borges and half-blind Harrison read voraciously. And Marquez, who insists he doesn’t read at all, cites Dos Passos, Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, Yasunari Kawabata, and endless others. Borges critiques Joyce in a way I found hard to dispel. Percy has a similarly incisive critique of Faulkner, but admits he was still under the spell of The Sound and the Fury when he took the English placement exam for college. He wrote it in “Faulknerian,” he says: one breathless paragraph without punctuation or capitalization. He was placed with the handicapped.

Marquez loves Faulkner and Harrison loves Marquez and everyone loves Chekhov. “Reading Chekhov was just like the angels singing to me,” sighs Welty. Many borrow prompts from other writers. Kipling’s “Drift, wait, obey” delights Robertson Davies. The motto Kafka wrote on the wall over his bed, Warte, is Percy’s favorite. Wait, he says:

You don’t have to worry, you don’t have to press, you don’t have to force the muse, or whatever it is. All you have to do is wait.

“It’s a struggle, a struggle against the book which won’t reveal itself, which refuses to reveal its mysteries on schedule. Books reveal their mysteries in their own good time,” says DeLillo. “You just have to wait.” You don’t have to drift or wait long “if you’re lucky,” says Davies. “But you jolly well have to obey. Because if you start pushing your characters around they’ll go dead.”

Then DeLillo gift wraps this paradox:

There’s a zone I aspire to. […] First you look for discipline and control. You want to exercise your will, bend the language your way, bend the world your way. You want to control the flow of impulses, images, words, faces, ideas. But there’s a higher place, a secret aspiration. You want to let go. You want to lose yourself in language, become a carrier or messenger. The best moments involve a loss of control. It’s a kind of rapture.

I have more than a dozen volumes from this series, and each writer stresses a variation on DeLillo’s theme. There must be a marriage of technique and inspiration, of control and risk. Faulkner likens the writer to a carpenter. “When he needs a tool, he just leans back and gets the tool he thinks will work. He doesn’t sit and think of which tool to use.” But he has to work hard as a carpenter first to reach that place of intuitive ease. “Writing is learned by writing,” Marquez insists.

All are asked to advise young writers. Here are some replies:

Faulkner: “Don’t be ‘a writer’ but instead be writing. Being ‘a writer’ means being stagnant.”

Jim Harrison: “Just start at page one and write like a son of a bitch. Be totally familiar with the entirety of the Western literary tradition, and if you have any extra time, throw in the Eastern.”

Jorge Luis Borges: “I would give him a very simple piece of advice: not to think about publication but about his work. Not to be in a hurry to rush into print, and not to forget nothing that he can’t honestly imagine. […] If there’s one moral defect that’s usually obvious in a work, it is vanity. […] A writer ought to be skillful, but in an unobtrusive way.”

Wendell Berry suggests giving up the driving urge to be a writer. This helped him discover that there are “other kinds of work also that required artistry and offered satisfaction.” It was a defining moment for him. “I had, in effect, decided not to be a ‘professional’ writer, but instead, in a literal sense, an amateur: I would work for love. I would be attempting a life, not a career.”

Robertson Davies seconds this, calling it “the law of overcompensation. You know, you try too hard, you inhibit success.” Like the golfer who seizes from too much effort, “you foozle the shot. This can happen in a great many other things, too. If you’re always telling life what to do, life won’t like it, and will revenge itself very sharply upon you. And that’s not mystical nonsense. It’s a thing you can observe.” The advice he gives young writers is: “Don’t plan your life too much. Let things happen to you. Much more interesting things will happen to you than you can devise for yourself.” That doesn’t mean not to have goals or plans, he says, just “don’t shut out the element of chance.”

A stranger once appeared at Walker Percy’s door and announced, “I want to be a writer and somebody told me you could tell me how.” That young man “wanted to be magically transformed into another category. He wanted to be a what a writer is,” sighed Percy. But “the only way you become a writer is the obvious: Write.”

Addressing the trend toward writer-celebrities, the pressure to Be a Write

r, rather than to be writing, DeLillo says, “There are so many temptations for American writers to become part of the system and part of the structure that now, more than ever, we have to resist. American writers ought to stand and live in the margins, and be more dangerous.”

I savor this advice, but would calibrate it. I’ve spent my life in the margins, being by nature solitary. Writers now toggle between invisible or over-exposed, while the craft itself, especially as it’s now taught, tilts toward solipsism. As Berry reminds us in “

The Specialization of Poetry,” this isolation is dangerous because the nature of “both song and story” is “communal.”

Our midnights at the desk are always solitary. But stepping into the flow of these literary conversations revives and inspires me. In these volumes, as in all books, we can find companions and teachers, and infinite solace.

This is Carol’s fourteenth post for Get Behind the Plough.