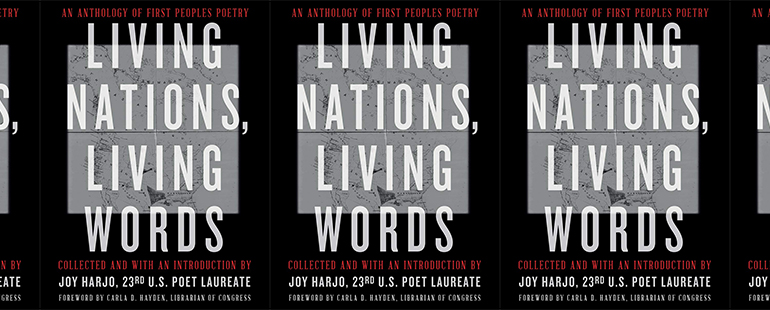

Mapmaking and Living Nations, Living Words: An Anthology of First Peoples Poetry

Joy Harjo’s signature project as the 23rd U.S. Poet Laureate is one of mapmaking: gathering poems by 47 Native Nations poets in a cartography of voice. Living Nations, Living Words: An Anthology of First Peoples Poetry, which was published in May, is the print version of this project, which also lives as an online multimedia map hosted by the Library of Congress. The online map bears no borders or labels; instead, its markers, shaped like small orange sunbursts hovering over the vivid topography, link to portraits and brief biographies of the poets, each of whom chose the location with which they are identified. These biographical introductions link to pages with audio recordings and transcripts of the poets reading and then commenting on their poems.

The print edition maintains this emphasis on the poets themselves: each of the 47 poems is preceded by a full page devoted to the poet’s portrait and brief biography. The anthology does not reprint the commentary recorded online, nor can it replicate the experience of hearing the authors’ voices. The audio recordings are particularly compelling because many of the poems are threaded with the poets’ traditional languages, and some appear fully in the original language and then English translation, including Ofelia Zepeda’s “B ‘o E-a:g maṣ ‘ab Him g Ju:kĭ/It is Going to Rain” and Ray Young Bear’s “Wichihaka/The One I Live With.”

But while the online collection offers an incomparable immersion in languages and voices, the print anthology is a compelling complement, correcting a gap in the canon of U.S. literary production. As Harjo notes in her introduction, “You will rarely find us in the cultural storytelling of America, and we are nearly nonexistent in the American book of poetry.” Publishing the project as both an online resource and a printed book thus underlines the both-and nature of Harjo’s project: both to record the oral cultures of Native American poets and also to emphasize their rightful place in the broader literary community.

The print anthology also complicates the map metaphor. Both versions begin with introductions that muse on mapping: “The very first maps were drawn into the earth with stick or stone implements,” Harjo writes, although “the earliest indigenous maps of North America were not drawn” but were built into villages, baskets, songs. The printed project, however, unlike the online version, maps not according to geography but through the four directions’ meanings, which organize the book into three sections. Harjo explains, “We begin with East, or Becoming,” “the sunrise place,” before moving to a section on “Center, or North-South,” “the belly and heart of presence and knowledge, of understanding,” “the crossroads.” The book’s last section is “Departure, or West.” These directional characterizations structure a readerly journey through origins to negotiations and finally hopes, although Harjo also insists one can begin anywhere in the collection. The result is a book of poems that offers an orientation toward the future: “We must make a new map,” Harjo writes, “together where poetry is sung.”

This future orientation relies on deeply rooted histories, and many of the poems tell origin stories. Imaikalani Kalahele’s “Maoli,” for example, opens:

In the beginning there was a voice

and the voice was MaoliSinging from before

the first footprint

on our sands

The poem reframes the familiar biblical opening to assert a reality before the colonizers’ religion. This cosmology, with Maoli “telling the first stories / singing the first songs,” transmits a history, a pre-contact memory that resists the erasures of colonization. The poem unforgettably ends with a powerful play on capitalization, using the colonizers’ language to resist the colonial history:

Before had england

even before jesus

There was a voice

And the voice was Maoli

In “Within Dinétah the People’s Spirit Remains Strong,” Laura Tohe offers another gathering of origin tales: “They say long time ago in time immemorial: / the stories say we emerged from / the umbilical center of this sacred earth into the Glittering World.” Mahealani Perez-Wendt, likewise, offers in “Na Wai Eā, The Freed Waters” a “Story of the People / of Ko’olau Moku, Maui Hikina.”

Other poems relate more recent family histories, like Elise Paschen’s “Heritage” and Leanne Howe’s “1918 Union Valley Road Oklahoma,” as well as histories of colonial displacement and loss. Toward the end of the middle section, three poems—“The Book of the Missing, Murdered and Indigenous—Chapter 1” by M. L. Smoker, “like any good indian woman” by Tanaya Winder, and “Poem on Disappearance” by Kimberly Blaeser—highlight the devastating vulnerability of indigenous women as well as their strength. “Conjure with your hands the shape of girl,” Blaeser writes,

blooming, curves of face, her laughing eyes;

you’ve seen them postered and amber-alerted—

missing, missing, evening newsed, and gone.

Blaeser’s poem connects the epidemic of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls to the colonial history of the continent itself, “reshape[d] by discovery, displacement.” The image refuses any explanation of indigenous women’s present-day experience that forgets its origins in colonial disappearance.

Identity is at the heart of many of the poems. Lehua M. Taitano’s “Current, I” evocatively muses over procreation and power, queerness and relation. In “i gotta be Indian tomorrow,” Nila Northsun writes of the pressure to perform a certain identity for invited appearances while realizing her poems aren’t full of “mother earth or feathers or reservations,” even though her life contains all three: “is that indian enough / for them?” “Antiquing with Indians” by Tiffany Midge unearths racist cultural artifacts, the “Battle of Little Bighorn / board game” and dolls of “Pocahontas and John Smith (what a pair!),” exposing the commodification of stereotypes and false histories. Anita Endrezze’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at an Indian” similarly interrogates stereotypes and the complexities of heritage and community, from the myth of “skin as coppery as a penny” to the challenges of preferred terminology persistent trickster presence of Coyote. It ends in persistence:

Today lasted centuries. Coyote sits next to me,

whispering promises of survival: mañana. It is tomorrow

and will always be tomorrow.

Stars shine all day, forever, and we don’t see them.

Our souls, whether white or ndn or Other, shine even longer.

There are more than thirteen ways of seeing anyone.

Indeed, for every poem of mourning there is a poem of resistance and creative power. “Indigenous Physics: The Element Colonizatium,” by Deborah A. Miranda, playfully and provocatively imagines colonization as a toxic substance, parsing out its “half-life” and figuring the power of “Story, Dance, Song, and Dreaming” as elements of transformation:

when applied to the Colonized subject,

these four elements

hasten the decay of Colonizatium,

pull the heavy history into themselves,

break it downthe same way maize, mustard greens, pennycress,

sunflowers, Blue sheep fescue, and canola

transform heavy metals.

Miranda here links cultural production—story, dance, song, dreaming—to gifts of the land, the plants’ wisdom and power.

This emphasis on the land and the water runs throughout. Jake Skeets’s poem “Daybreak” opens the collection with vivid images of place:

Roberta Hill’s “These Rivers Remember” sings of “the flow of rivers / and their memories of turning / and change,” as well as “roots of the great wood” that “are swelling” below the city of St. Paul. Gordon Henry Jr. likewise writes in “River People—The Lost Watch” of stories of life “when we were river people”—not in a distant past but a recent memory. And Layli Long Soldier’s “Resolution 2” emphasizes the land as a present and persistent reality, as the poem’s representation of official commendation of Native People’s “stewardship,” which runs down the left side of the page, is interrupted by the dispersed repetition of the words “this land,” suggesting a tension between governmental praise and material justice.

The form of “Resolution 2,” with its dispersed words and invitation to a visual and non-linear interpretation, highlights the anthology’s formal variety. There are prose poems and musical lyrics, long narrative verse and experimentally sparing pieces. Some of the poems gloss their traditional languages while others leave the words and phrases unexplained. The result of all this variety is a collection in which the shared experiences of colonial displacement and violence, gender negotiations, and creative resistance exist alongside multitudinous particularities: particularities of language and culture, place and perspective, poetic and political approach. In this way, the book maps a variety of paths forward, refusing the lie of a generalizable Native American identity even as it crafts a coalition of shared purpose seeking justice and flourishing for First Peoples, the land, and all its animal, vegetable, and mineral life.

Living Nations, Living Words insists on the present and future vitality of First Peoples, refusing another lie that would place indigenous peoples in a frozen past. These nations—and these words—are living, even at the points where their lives bear witness to injustice. The urgency of this project is hard to overstate given another map that has been emerging over the past few months, a map of old news confirmed by new technologies, news of the remains of more than a thousand people so far found in unmarked graves on the grounds of residential schools where indigenous children were taken in the genocidal project of colonization. This map confirms the stories survivors have told for generations, and while at present it is most densely marked north of the U.S-Canada border, Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland has committed to seeking the truth about these horrific histories within the boundaries of what is now known as the United States. The map’s plot points will continue to accrue, and the grief will continue to overflow any geographic lines.

Harjo’s poetic map acknowledges this other map of colonial violence and erasure, and while poetry can offer no full answer to the pain, it can bear witness. Tanaya Winder names the losses’ legacies in the opening lines of her poem “like any good indian woman”:

I pull my brothers from words, stupid injun, shot like bullets. when people ask why my brothers hated school i say: the spirit remembers what it’s like to be left behind when america took children from homes, displaced families with rupture, ripping a child’s hand from a mother’s to put them in boarding school buildings.

In the past month, I have heard many settlers grieve aloud how little they’ve known of this history of residential schools. I have also heard Indigenous friends name how painful it is to listen to settlers make this strategic move to innocence—the histories have been told all along. And even as the news of these unmarked graves emerges, the United States is embroiled in controversies over how we tell our national history, over which parts of the unjust past will be named and which parts again silenced.

In her introduction, Harjo recognizes the project’s urgency given the times: “The mapmaking represented by this anthology comes at a crucial time in history, a time in which the failures to acknowledge, listen, and to consider everyone when making the map of American memory has brought us to a reckoning.” For its part, Living Nations, Living Words reckons with this crossroads by drawing a truer map, a fuller map unapologetic in its anger and its hope, its emphasis, in Harjo’s words, on “visibility, persistence, resistance, and acknowledgement.” This is a map not just of where the nation has been—where the nations have been—but of where we might go. And so it is fitting that the last few poems voice different paths that circle back to find the way forward: “In Beauty it was begun,” insists Laura Tohe. “In Beauty it continues.” Several pages later, in “Postcolonial Love Poem,” Natalie Diaz writes, “There are wildflowers in my desert / which take up to twenty years to bloom.” She concludes with an open-ended admission that the work is far from done:

The rain will eventually come, or not.

Until then, we touch our bodies like wounds—

The war never ended and somehow begins again.

This piece was originally published on July 14, 2021.